Over 15 years of ocean science and conservation online

Biden unveils an Ocean Climate Action Plan

President Biden unveiled the nation’s first climate action plan specifically targeting ocean health. The Ocean Climate Action Plan advance several key climate initiatives, including providing 40% of federal investment benefits relating to climate change to disadvantaged communities; producing 30 gigawatts of energy from offshore wind by 2030; conserving at least 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030; and achieving zero emissions from international shipping no later than 2050. It’s a huge step forward and possibly one of the most consequential pieces of ocean policy since the Guano Islands Act.

Biden also announced plans to expand the Pacific Remote Islands Marine Monument, this would dramatically increase the proportion of protected oceans in US waters and get us closer to the 30 by 30 goal. The call also includes potentially renaming the Monument and several of the islands to recognize the history and heritage of Pacific islanders rather than the legacy of imperialism and colonization.

No word yet on the expansion of the Marianas Trench Marine National Monument.

This month, delegations from around the world agreed upon a treaty to protect biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction — ocean life beyond the limit of any country’s borders. The High Seas Treaty represents the culmination of over 2 decades of debate and negotiation. Once adopted, it establishes a framework for the protection and equitable sharing of marine genetic resources — animals and their DNA; promotes the implementation of marine protected areas in the high seas; and creates a scientific and technical body to review environmental impact assessments for ocean activities beyond borders.

While this treaty is a monumental achievement for protecting the common heritage of humankind, it still leaves several loopholes for ocean exploitation. Chief among them is the exemption of deep-sea mining from the final regulations.

Read More “What does the high seas biodiversity treaty means for the future of deep-sea mining?” »

Two years ago, I set out on a little mission: to build an off-grid solar array that would power my woodshop. This array needed to charge all my cordless batteries, but also drive my table saw, miter saw, circular saw, and the big router on my slab flattening jig. But there was a catch. The entire system could cost no more than one American Recovery Act stimulus check.

That first build can be found here: I turned my woodshop into a personal solar farm.

It worked. I beat the heck out of that set up and, other than in the dead of winter when it was too cold for the battery, it could handle most everything I threw at it, pretty well. It wasn’t perfect, and it had some issues with overdrawing, but the safety stops I put in place ensured that when I did push it too hard, it shut itself down rather than compromising components. There were limits, though, as I added bigger tools like a bench planer and started hogging through much tougher stock, I began to run into more and more issues.

So here we are, 2 years later, with all the upgrades and modifications that I made to my off-grid workshop to keep things running hard.

Read More “Woodworking off the grid: upgrades to my DIY solar workshop” »

In the Last of Us, the most gruesome live-action adaptation of a video game about people being turned into fungus since 1993’s Super Mario Bros, a mutated species of Cordyceps destroys society by converting humans into mindless, sporulating mushroom people.

Cordyceps, a fungus that most commonly parasitizes ants, is real. It really does hijack its host’s nervous system, alter its behavior, and turn it into a spore-producing zombie. The outcome is strangely beautiful.

Though the current darling of gritty, realistic, science-based zombie fiction, Cordyceps is such a lightweight in the world of brain-breaking parasites that tech bros brew it into their adaptogenic coffee.

If you want to meet a truly unsettling zombie-making parasite, allow me to introduce you to Sacculina.

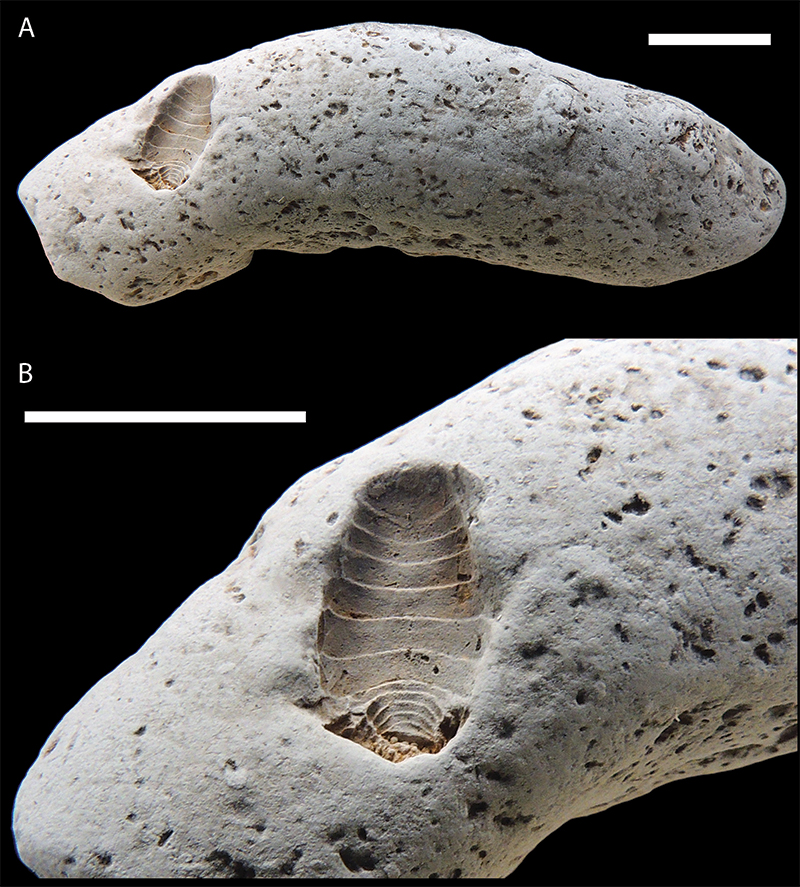

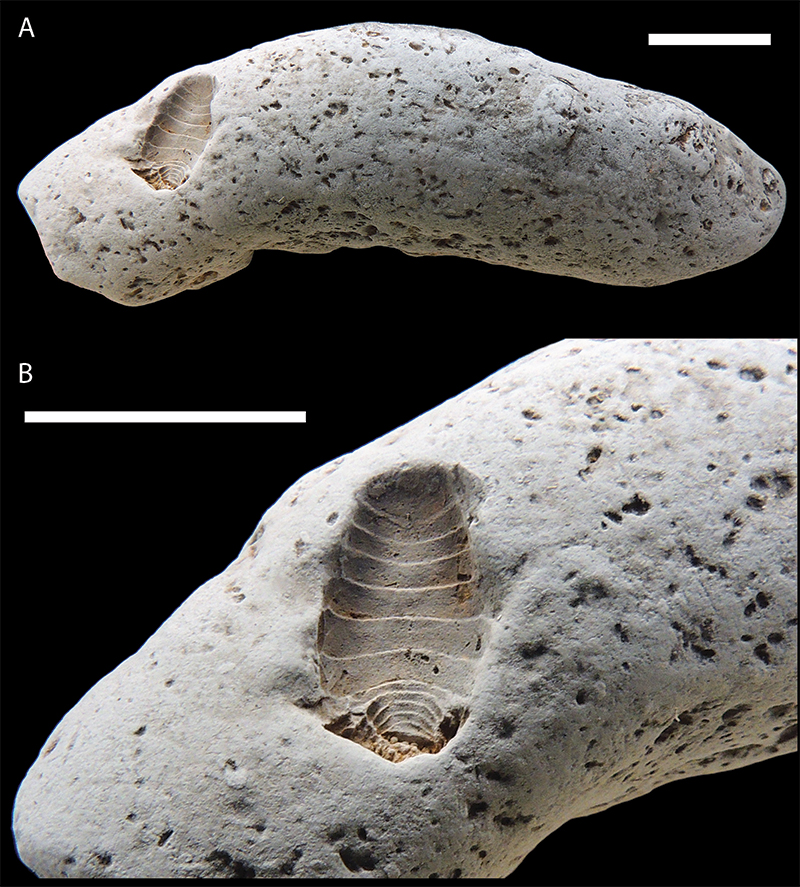

Sacculina is a genus of barnacle that parasitizes crabs. While most parasitic barnacles are perfectly happy growing on the carapace of a crab, Sacculina takes this partnership to the extreme.

Female Sacculina larvae drift through the ocean, until they encounter a crab. The larva then settles on the crab and searches for a joint in the crab’s carapace. Once it finds a gap in the arthropod’s armor, it transforms into a kentrogon, a specialized phase of the barnacle life cycle that possess a stylet–an organic syringe-like structure–which allows Sacculina to inject itself into the crab, and not much else. At this point, the hard shell attached to the crab’s carapace falls off and the barnacle continues to grown within its host.

It gets so much weirder from here.

This piece originally appeared in the farewell issue of the Deep-sea Mining Observer.

Four years ago, I took over the Deep-sea Mining Observer from my predecessor, Arlo Hemphill. Conceived by the Pew Charitable Trust in 2016, The DSM Observer was created to be an online trade journal for the emerging industry as the International Seabed Authority navigated through the creation of an Exploitation Code for Seabed Minerals in the Area. Originally envisioned to run for two years, we continued to cover and report on critical developments into 2022.

After six years, the Deep-sea Mining Observer is coming to close.

During my tenure here, I tried to capture the full breadth of issues surrounding deep-sea mining. We covered the first species to be IUCN Red Listed due to the potential threat of mining. We examined the rise and fall of Nautilus Minerals. We reported the launch of the Patania II nodule collector test vehicle. We investigated how bioprospecting, often put forward as an industry in potential conflict with deep-sea mining, works in practice. We explored the complex political and geologic history of the Rio Grande Rise. We looked at how new technologies may change the financial landscape for seabed mining. We tracked a semi-mysterious cache of polymetallic nodules from the CCZ offered for sale. And we looked at how other industries intersect with deep-sea mining.

2022 has been a weird year for humans, but it was a very interesting year for sharks! Shark species representing 90% of the global shark fin trade got listed on CITES Appendix II, which will require strict regulation, documentation, and dramatically improved sustainability of their fisheries. The once-every-four-years Sharks International conference was held in Valencia, Spain, and recordings of all talks are available until summer 2023. And sharks even made it into one of those “what Fox News is showing instead of current events that are bad for Republicans” memes!

There were also a lot of fascinating scientific discoveries, which this post will round up for you. As always, this is not meant to be a “best” or “top” list, so if your science isn’t included here please do not send angry letters. This is just some cool stuff I learned this year thanks to my amazing colleagues, in no particular order. Whenever possible I’ll also provide links to further reading on the topic. I hope you enjoy!

Read More “22 things scientists learned about sharks in 2022” »

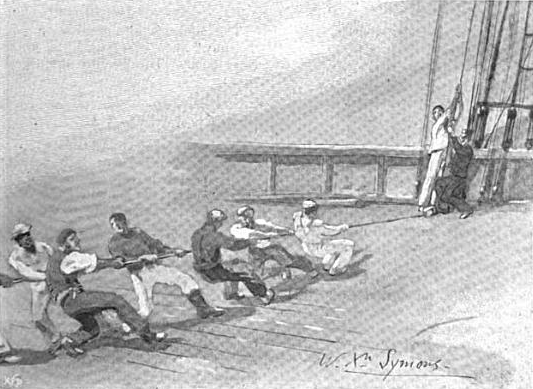

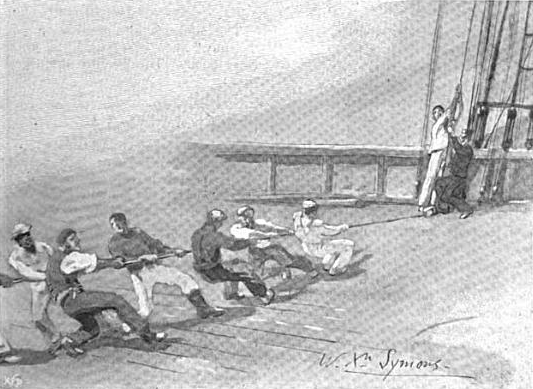

The hot new thing on the internet is the latest revival of a centuries-old musical tradition. The humble sea shanty has taken the internet by storm, with remixes of remixes getting millions of views. The phenomenon written up in The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and CNN, and inspired an SNL skit.

As a marine biologist who learned to sing many of these songs to pass time on research vessels while honoring maritime traditions, I’ve loved watching this style of music spill all over my social media feeds, letting a new generation experience them. (Watch this man’s skepticism quickly fade to joy as he listens to Wellerman and tell me it’s not one of the purest things you’ve ever seen).

However, reading people’s explanations of why Sea Shanties are The Next Big Thing has made me realize something important: I didn’t know as much of the history of this style of music as I thought I did, and I’m not alone—much of the information contained in the articles I linked to above is oversimplified or even incorrect (Wellerman is a maritime song, but isn’t really a sea shanty, for one egregious example). As I began to ask around, I realized that there isn’t a single authoritative and thorough article about the history and culture of the sea shanty written for lay audiences anywhere on Al Gore’s internet. So I decided to dig into the literature, speak to experts, and write one myself. I hope you enjoy it!

These are my active social media accounts: Twitter (automated posting): https://twitter.com/DrAndrewThaler Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/drandrewthaler Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/drandrewthaler/ TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@drandrewthaler Mastodon: https://mastodon.social/@DrAndrewThaler Project Mushroom: https://projectmushroom.social/@DrAndrewThaler

I know, I know. I started this series and then totally lost track of it. It needs an update and a fresh coat of finish. Fortunately, a few chats about getting started in woodworking inspired me to put some more work into my ridiculous woodworking manifesto.

This is Part 5 of Built to Last: A Reflection on Environmentally Conscientious Woodworking.

I’ve been woodworking my whole life, but this merger of science, conservation, woodworking, and the environment began with what remains one of the most popular articles on Southern Fried Science: How to build a canoe from scratch on a graduate student stipend. That was my return to serious woodworking after almost a decade and one fun way to celebrate passing my prelims.

So what do you actually need to get started woodworking?

You really don’t need nearly as much to get started as the woodworkers of YouTube may lead you to believe. Sure, as you progress you may want a really nice sander, you may find a domino joiner appealing, you might want to drop $1000 on a full set of nice hand planes, or maybe you start investing on milling machines.

But, at the beginning, you need something that cuts and something that connects. My freshman year of college, David Shiffman and I started a ridiculous company that recovered used lofts from dumpsters and dorm rooms at the end of the year, stored them over the summer, and then sold them back at a steep discount to incoming students as a recycled alternative to building a new loft. They had character.

We had exactly two power tools between us. A corded Skil drill that I paid $20 for and didn’t even have variable speed, and a very old corded jigsaw from a brand that doesn’t even exist. A hammer, a cheap handsaw, and the screwdriver that came in my truck’s spare tire kit rounded out our arsenal. We disassembled, rebuilt, and modified thousands of lofts using those tools. It really doesn’t take much.

The third part of the 27th session of the International Seabed Authority, a meeting where the rules and regulations about how the deep ocean will be mined, begins today. If process is your jam, you can watch the UN negotiations here: https://isa.org.jm/web-tv

For a very concise overview of where we currently stand, I published the transcript of my recent talk, here: Deep-Sea Mining: A whirlwind tour of the state of the industry and current policy regimes

Some recent press to get you up to speed