Debate over a communications study investigating science blogs and public engagement has recently engaged some of the research subjects and their friends to review the paper, which they’re totally entitled to do. Except that they, as traditional natural scientists, may not have the tools at hand to do justice to such a review. Dr. Isis’ response to the article may have been a bit dramatic but not entirely off the mark. The study was well-grounded within social studies of science theory, but perhaps not executed or written like a seasoned researcher, which I suspect the author’s not. So, beyond the fold, my social science perspective on the paper…

Debate over a communications study investigating science blogs and public engagement has recently engaged some of the research subjects and their friends to review the paper, which they’re totally entitled to do. Except that they, as traditional natural scientists, may not have the tools at hand to do justice to such a review. Dr. Isis’ response to the article may have been a bit dramatic but not entirely off the mark. The study was well-grounded within social studies of science theory, but perhaps not executed or written like a seasoned researcher, which I suspect the author’s not. So, beyond the fold, my social science perspective on the paper…

First, kudos to Inna for a good introduction, grounding the study in appropriate literature within science and technology studies, specifically articles discussing the democratization of science and types of knowledge in science creation. She proposes to add to this literature by investigating blog comments as a means of adding to scientific discourse and discovery. Whether she accomplishes this goal is debatable, as she later reports that all forms of participation (contribution, digression, expression of attitude or emotion, or call to action) were present in the comments, so it was hard to draw any conclusions about the role of commenters in scientific production.

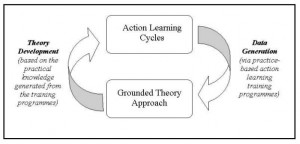

What most of the responses thus far have hinted at is the methods chosen for the study. I can vouch for the fact that they are standard social science qualitative methods. Most of us have spent countless hours coding as described by the author’s article, generally aided by a computer program called NVIVO. She used a method of coding commonly referred to as ‘grounded theory’ (yes, we like to make up jargony names for absolutely everything) in which the researcher doesn’t start analyzing with a prescribed set of codes, but instead allows the ideas and concepts that are most prevalent to emerge through the research process. Ok, all kosher so far.

Where I start to have a problem with her methods begins with how she chose her study blogs – a Google search on “science blogs” and “blogs about science”. First, this biases the sample toward the science blog network, but she probably didn’t know that prior to work on the study.

Also, she didn’t specify whether she was attempting to get a representation of widely read and accepted science blogs or a broader sample to cover the spectrum of self-proclaimed science writing in the blogosphere. If the former, the Google search would have had to been more prescribed and included some method of random sampling (such as taking every 10th result). If the latter, then the author would have been far better off contacting some blog authors and asking for recommendations of well-respected science blogs or reading the blogrolls and identifying commonly read blogs (this is tantamount to finding key informants, a strategy commonly employed by exploratory social science research). In this case, the sample size of 11 isn’t really small because all are good representations and you can delve deeper into the content of each blog.

From the sample of 11, first, they aren’t all blogs (Panda’s Thumb) and aren’t all active (BioEthics) but she didn’t discount them because of that. Also, in order to even out the amount of material analyzed, she took a longer sample (30 days) of less active blogs and short sample (5 days) of more active blogs, meaning that she probably got more content-driven discourse out of the more active blogs covering one or two exciting posts rather than a more representative sample over time.

In addition, she only included the first 15 comments in yet another effort to trim the amount of material she had to code and analyze. I can sympathize with this notion, but question the implications of focusing on the first 15 comments – would that tilt the analysis toward the regular readers of the blog who first read the article? Would this really matter, ie. are those people different than the ones who join the discussion later? It’s really a whole different research question, and perhaps one that badly needs to be answered.

In the end, the biggest question asked of any social science study is ‘how is this applicable to a larger scale generalization’? Some in the field call it big T Theory. Others are quick to point out that case studies are just that… case studies – and not uniformly scalable to larger conclusions. I would say that this is the case for the study in question. The results are certainly accurate for the 11 blogs in focus and can at least be informative to the authors of those studies when considering their readership.

The conclusions that the comments and discussions are not that different from traditional print media in fostering scientific knowledge creation is also potentially true, on average. I know a lot of great science bloggers out there, but I also can name quite a few that aren’t so stunning and even more that don’t foster much discussion. So I’m not exactly surprised by her results and I certainly don’t disagree with them. In fact, she also identifies most of the readers as people with a scientific background given the content and tone of their comments, which then begs the question why don’t we have more thoughtful discussions? She’s totally right in concluding that the challenge is out there to make better use of the new tool of the blogosphere to foster scientific thinking.

So quit quibbling over the disciplinary divides regarding methodology, take her conclusions to heart, and get commenting.

~Bluegrass Blue Crab

You know what would have made this post better? Pictures of sheep. But, nice work nonetheless.

Her methods may have been valid qualitative methods, but coding yields results and yet there is no data provided to the reader in the results section. I also find it difficult to figure out how she concluded that the readers are people with a science background. She mentions looking at a poll from one blog, and maybe some attempts to infer from the comments, but surely this is not the most robust methodological approach she could have used. Only a small fraction of readers comment. That’s not necessarily unique to this medium.

“focusing on the first 15 comments – would that tilt the analysis toward the regular readers of the blog who first read the article? Would this really matter, ie. are those people different than the ones who join the discussion later? ”

Just with respect to some of my most comment-getting posts, the ethical debate series, the first 15 comments are not at all representative of the rest.

The first 15 are usually regular readers and facebook friends who see me post a “join the discussion” link.

In the rare cases when people who don’t already know me think I’ve written something worthwhile, we have gotten linked to many months later, bringing a whole different set of comments from people of many diverse backgrounds.

Once a semester (often long after the posts themselves are written and many comments in), my introductory biology students join the discussions.

In one case, a middle school science class participated in a discussion. This was after 50 or so comments were already there.

In short, yes, I think the people who write the first 15 comments can be drastically different from the rest of the people who write comments.

I totally agree that she didn’t have the data to back up conclusions on readers in general rather than just commenters, but I am curious now to know if that’s true. Overall I think the study needed some mixed methods, that is interviews with the authors or surveys of the actual readers. That would strengthen her arguments and give her a lot of the insights that have been brought out over the blogosphere discussion of her article. Maybe a next step?