Mareike Dornhege is currently finishing up her PhD on shark fisheries in Japan. She is based in Tokyo at Sophia University and after seeing no sharks many times were there should be sharks on reefs all around the world she wanted to dig deeper and find out when we lost them, why and where. She is trying to reconstruct baselines by looking at the history of sharks and humans, talking to old fishermen and of course modern data as well. And she really loves going on that shark-feeding dive about 90 minutes south of Tokyo!

Mareike Dornhege is currently finishing up her PhD on shark fisheries in Japan. She is based in Tokyo at Sophia University and after seeing no sharks many times were there should be sharks on reefs all around the world she wanted to dig deeper and find out when we lost them, why and where. She is trying to reconstruct baselines by looking at the history of sharks and humans, talking to old fishermen and of course modern data as well. And she really loves going on that shark-feeding dive about 90 minutes south of Tokyo!

The latest shark thriller The Shallows just hit theaters—coincidentally with Shark Week around the corner – and is latest in a long line of shark thrillers. In the grand, yet predictable fashion of movies like Deep Blue Sea, The Reef or Open Water, it fuels our fear of the sleek ocean predators that was first awakened by the mother of all shark movies, Jaws, in 1975. Or, was it? It is only since the Jaws theme that got stuck in our heads, even if we are just paddling around in a swimming pool at dusk, and images of dangling legs under water, that we got so irrationally scared and obsessed with the well-designed teeth of these fish after all, right?

Actually no. During my research on the history of shark and men I came across some hair-raising anecdotes of monster sharks from the Caribbean and man-hunting mantas that are just a bit older. A few centuries that is. This fishermen’s yarn must be the pre-digital equivalent of this youtube video of a megalodon shark caught on tape, real mermaids, and dragon footage. Let’s look at what they say and then at what the real science behind these stories is.

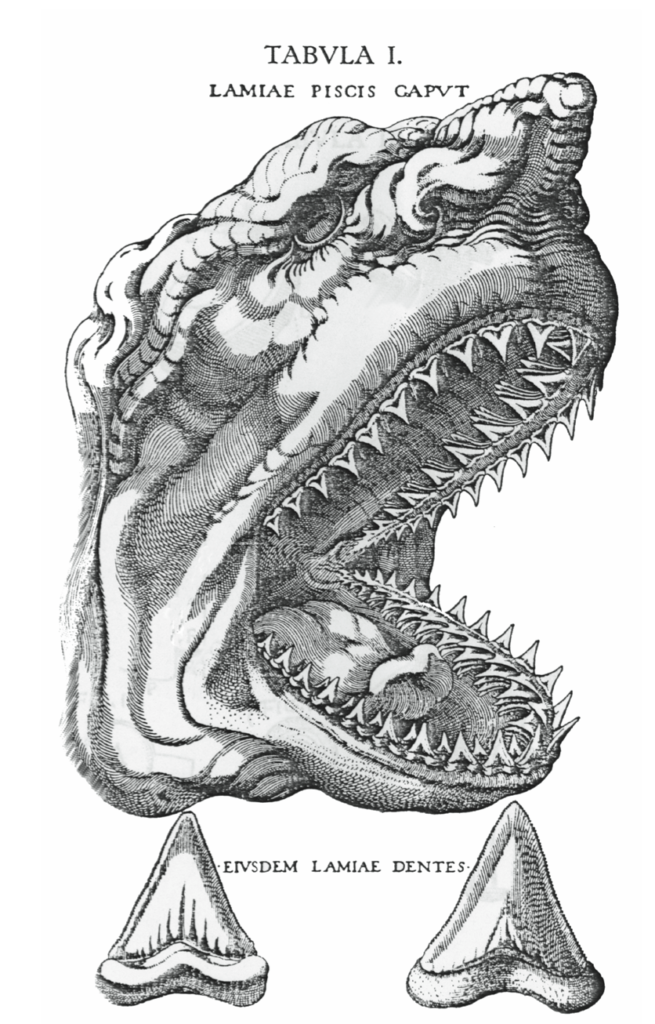

- This story from 1559, written down by a Spanish explorer in the New World, Las Casas, tells us of the sharks in the Caribbean:

“The tiburones (sharks) have admirable teeth and seize a man or a horse by the leg or by

the arm or any other part, and taking him deep, they kill him there, and eat him on their own time.”

So far, nothing special here. Now, let’s talk about the marrajos:

“The ‘marrajos’ are very much larger (than sharks) and have great mouths, and they can swallow a man on the first gulp.”

In his story, Las Casas describes how a pearl diver was attacked by such a monstrous fish. Witnessing this, his boat mates baited it with a hook and pulled it onto land:

“The Spaniard feeling that the fish was hooked, gave it enough line, and slowly returned towards the beach in his canoe or boat. Jumping to the land, he called for people to help him, they landed the beast, giving blows with axes and rocks or whatever they had, and killed it, opening its belly they found the unfortunate Indian and took him out, the Indian gave two or three gasps and he died there.”

Another Spaniard described the “marrajos” like this in 1535:

„The marrajo is a larger animal than the tiburón (shark) and fiercer, but not as swift (…). Of these I have seen some with nine rows of teeth…“

(all accounts from “On the origins of the Spanish Word “Tiburon” and the English Word “Shark” by Jose I. Castro, 2002)

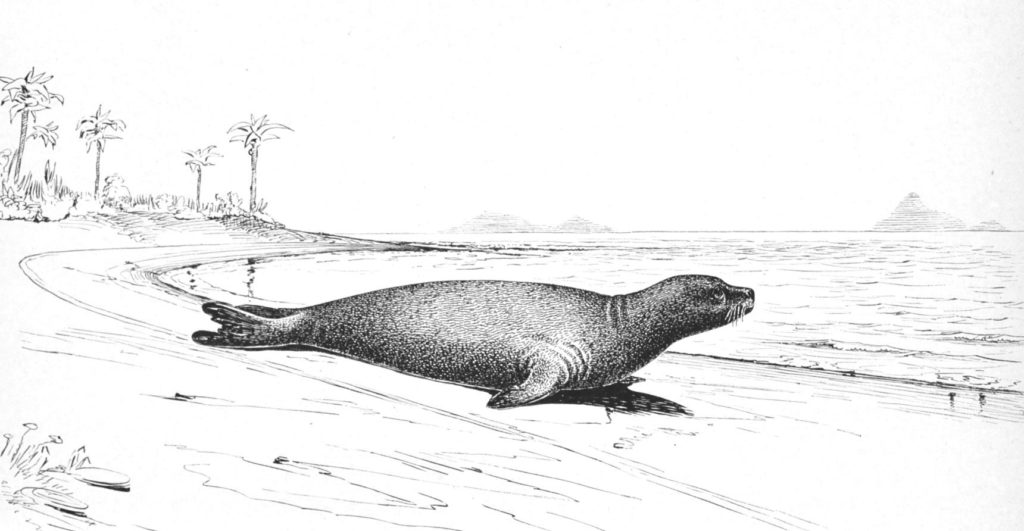

First off, the marrajo was probably a great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias). In the Caribbean, in the tropics? No way, you might wonder. But in the 16th century, Caribbean beaches were still inhabited by large colonies of the Caribbean monk seal (monachus tropicalis). Like seal colonies in Australia, South Africa or California, the monk seal aggregations probably attracted white sharks which patrolled the waters here. The Caribbean monk seal became so scarce by 1880 that is was considered almost mystical and finally went extinct in the 1950s, due to hunting pressure. And with it disappeared the great whites most likely.

Next up in the story, swallowed a man whole on the first gulp, so that he can be cut out of the shark’s belly unharmed again? This would be the first confirmed account of a shark attack where a shark actually wholly swallows a human. The majority of shark attacks result in the shark not taking any flesh at all. In most cases, sharks might bite, realize that we are not as tasty as their actual prey and let go again.

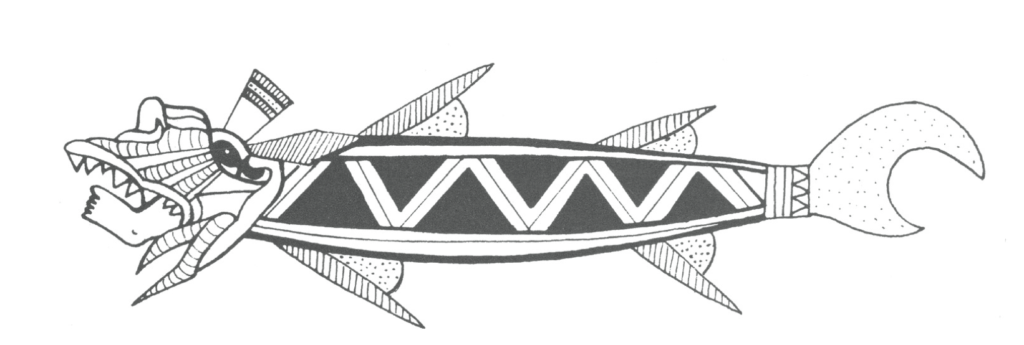

- There seems to be a sawfish (Pristidae) in every shark tank in aquaria around the world. Which is sadly also why many are not aware of how endangered this unique family of rays (yes, the are also known as carpenter sharks but they are actually rays) is in the wild. And apparently evil too:

“Among the dangers of the pearler in the Persian Gulf, the dreaded saw-fish may be mentioned as the chief enemy. This shark-like creature is furnished with a formidable weapon in the shape of a flat projecting snout, reaching a length of perhaps six feet, and armed along its edges with strong tooth-like spines. In the presence of such a terrific weapon the diver is almost powerless, and instances are recorded in which the poor fellows have been completely cut in two.”

(extract from the book “Travels in Arabia” – a record of the travels of Lieutenant J. R. Wellsted published in 1838)

No, sawfish do not cut people in half. They aren’t even dangerous unless provoked. The saw – or rostrum – is packed with sensors known as ampullary pores which can detect electric fields, which helps the fish to locate prey. However, sawfish can reach a length up to 7m, which is rather impressive and could have certainly scared ill-equipped skin divers two centuries ago. Habitat destruction and fishing pressure, both from by-catch and for ornamental purposes (people sadly want to get their hands on that rostrum – the sawfish saw), have decimated numbers so severely that it is unlikely for us today to encounter such large specimens anymore. But two centuries ago the population was most definitely larger and the sawfish larger, possibly growing up to their impressive maximum size.

- But everyone loves manta rays, right? Gentle giants, majestic filter-feeding rays flying through the oceans. Wrong again. Listen to this, written down by de Ulloa in 1748:

“The mantas squeeze them [the fishermen], enveloping them with their bodies or putting all their weight against them on the bottom; it seems that, not without reason, that the name manta [Spanish for blanket] was given to these fishes, from its shape and properties, the shape being as extensive and big as a blanket, it has the same purpose, of enveloping the man or other animal that it catches, squeezing it in such manner, that it makes [the victim] exhale its last breath by being compressed.“

(from “On the origins of the Spanish Word “Tiburon” and the English Word “Shark” by Jose I. Castro, 2002)

Mantas suffocating divers on purpose? I beg to differ. Mantas are known to sometimes tangle with mooring lines or boat anchor lines. So, it is likely that one of these gentle giants, swimming through the multiple lines dangling from a fishing boat, could catch one of the lines and pull an unfortunate diver against its side or pull it down, giving the appearance of enveloping the diver and dragging him to the depths.

So in the end, it was not Jaws after all that is to blame. The fear and the fear-mongering stories were already out there before, but confined to those who lived and worked around the sea. But with people starting to swim in the ocean for leisure and the new medium cinema things got blown out of proportion. If there is one thing we learnt, and keep on learning is that the more we know, the less we need to fear. Today we know that sharks don’t stalk humans, sawfish rostra are sensory organs and not superweapons and that mantas don’t want to drown people, as we learnt more about their behavior and biology. Let’s hope that shark week gets infused with a lot of that as well to put things back into balance.

And some of us wiser than others already knew this 2,000 years ago, as Pliny the Elder already stated in the 1st century A.D: “(…) a dog-fish is as much afraid of a man as a man is of it (…).“