Note: please see the update to this post – Updated financial model for deep-sea mining makes more sense, fewer dollars

This month, once again, the delegations from 169 countries will gather in Kingston, Jamaica to continue the negotiations on the Deep-sea Mining Code. At this point, I’ve written extensively about the potential environmental impacts of deep-sea mining, the opportunities and costs of developing the industry, and the progress on the negotiations. More and more, this year, I find myself thinking about the raw numbers and whether or not deep-sea mining really has the potential to be as profitable as is claimed.

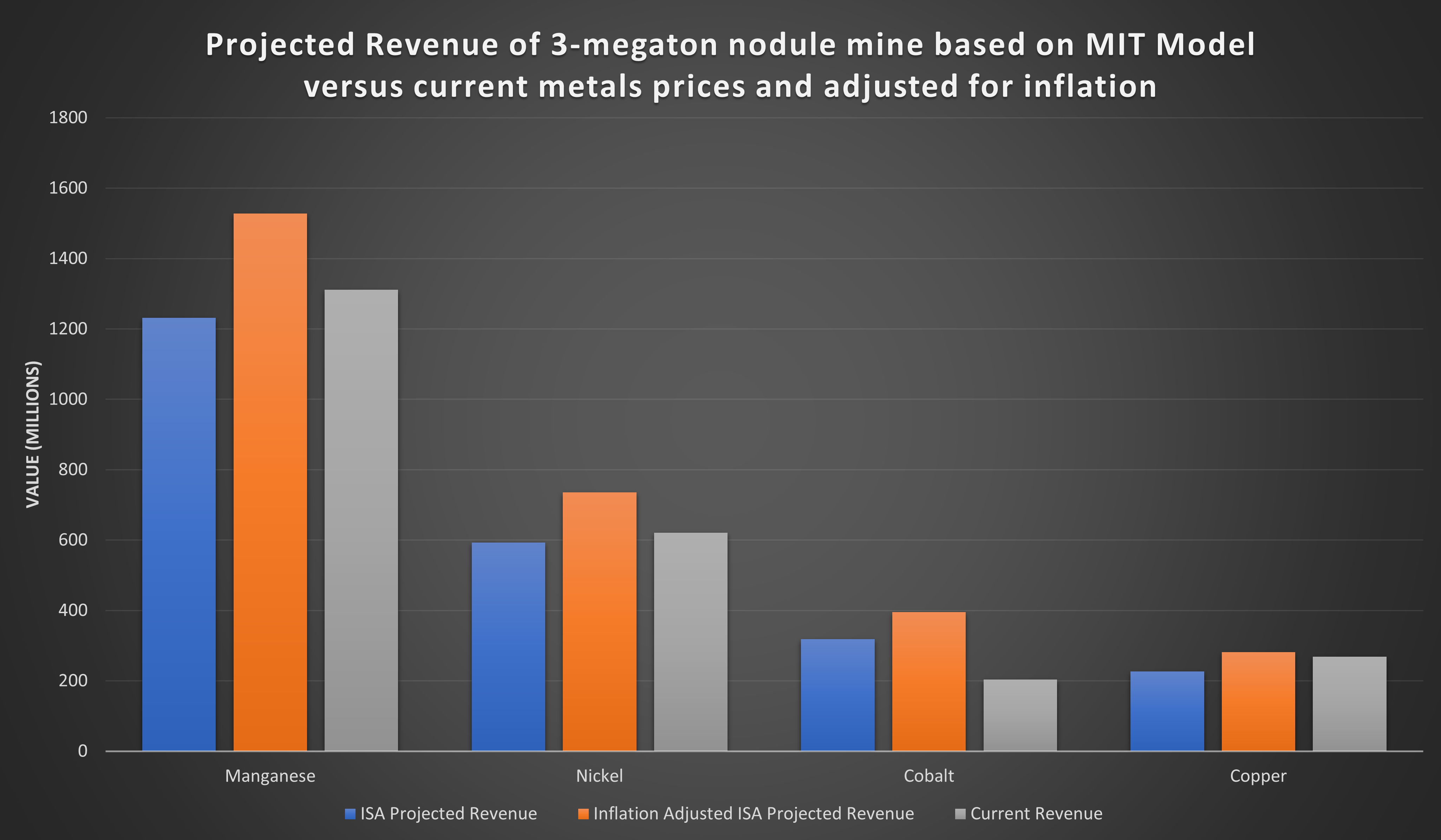

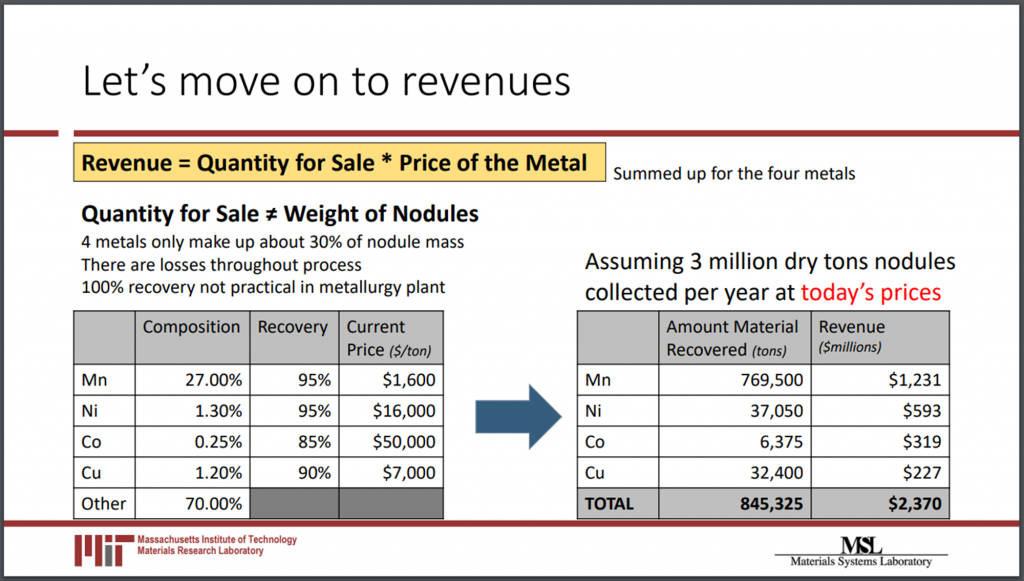

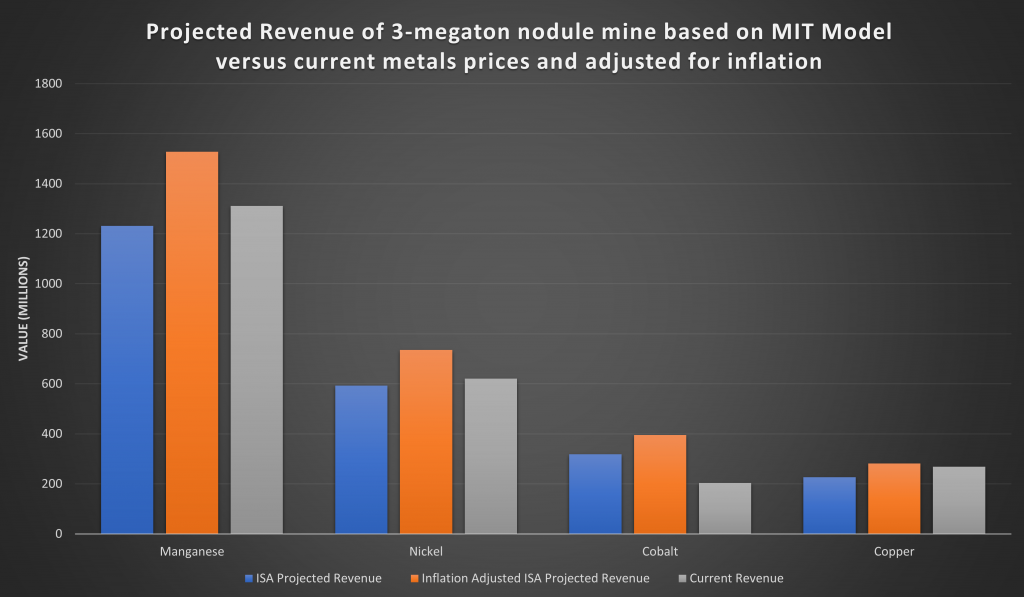

To better understand the potential value of a polymetallic nodule mine, the ISA commissioned MIT to develop a financial model based on a hypothetical commercial deep-sea mining operation. This proposed mine consists of a single mining vessel harvesting 3 megatons of polymetallic nodules from the Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone. When proposed in 2018, the total value of the mine came to about $2.3 billion per year, of which $1.2 billion is manganese, $600 million is nickel, $300 million is cobalt, and $200 million is copper.

Adjusted for inflation, that $2.3 prospect would be worth about $2.9 billion today.

Except, it isn’t. Prices have changed a bit since 2018, so I reran those numbers and adjusted them for both inflation and changes in the commodities market.

All but copper have fallen in value since the original projection, but not by much. At current prices (actually mid-January 2024), the 3-megaton mine is worth about $2.4 billion dollars. $2.4 billion is still a lot of money, but that mean that over the last 6 years, this hypothetical deep sea mine has lost half-a-billion dollars in value.

The price of these metals is extremely volatile. Cobalt famously spiked to over $80,000 per ton in 2018 and again in 2022, before falling back to just below $30,000 per ton, today. Nickel has had a similar, but less dramatic history of booms and busts. Currently, both nickel and cobalt are sitting in a historic surplus which is expected to last until 2030. But as we’ve seen several times in the last decade, that could change in a moment.

What we do know is that the world produced about 3.3 million tons of nickel in 2022, much of which came from environmentally destructive mining operations, especially in Indonesia which began rapidly expanding its nickel production. The 3-megaton deep-sea mine would produce about 37,000 tons of nickel, or about 1% of global annual production. It would take 55 3-megaton deep-sea mining operations working in tandem to match Indonesia’s 2023 nickel output.

Cobalt isn’t produced in nearly the same quantities as nickel. The world mines about 200,000 tons of cobalt, with about 145,000 coming from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The 6,300 tons coming out of a deep-sea mining operation could account for a respectable 3% of that production. That still requires 23 3-megaton deep-sea mining operations to match the output of just the DRC.

I continue to assert that deep-sea mining of polymetallic nodules is almost certainly less environmentally harmful that terrestrial mining for cobalt and nickel, but that there is no practical pathway in which deep-sea mining replaces these terrestrial industries. The impact is additive. And because the impact is additive and the scale is orders of magnitude off from where it needs to be, the urgency to go to sea for our metals does not exist. We can afford to take our time and get it right, so that when and if deep-sea mining becomes a major contributor to the global metals market, it is also a model for maximum environmental harm reduction.

But then there’s manganese. The manganese math doesn’t add up for me. When the hype for deep-sea mining was ramping up in the 1970s, manganese was the rage. We needed manganese for lots of things, but we especially needed it in steel production. That hype subsided as more and more studies revealed that even a very modest-sized deep-sea mining operation would produce ten times the US annual demand for manganese. But that was the 1970s. We need a lot more manganese now.

Most manganese is sold as ore and goes for about $4.50 a ton, at 35% manganese. South Africa produces about a third of the world’s manganese ore. The CCZ nodules clock in at about 27% manganese, so it’s not exactly high grade ore. The price in the MIT model, however, is not the price of manganese ore, but the price of electrolytic manganese, which is pure, elemental manganese and goes for about $1700 per ton. That makes sense to me, since the manganese is extracted when the nodules are refined for nickel and cobalt, so it shouldn’t be priced it as an ore.

We don’t consume all that much electrolytic manganese, globally. In 2009, which is when I could find the last reliable production numbers for electrolytic manganese, global consumption was at about 700,000 tons per year. Assuming a generous 10% projected growth (most estimates for manganese ore demand hover around 3% to 6%, I couldn’t find any good estimates for electrolytic manganese), that puts demand for electrolytic manganese at 2.6 million tons. At the 2009 numbers, a 3-megaton deep-sea nodule mine would exceed the world’s annual consumption of electrolytic manganese. At the optimistic projection of 10% annual growth, one deep-sea mining would meet almost 1/3 of the world’s manganese demands.

Cobalt and nickel prices plunged on relatively minor surpluses. I can’t even begin to speculate on what a 30% to 100% surplus does to the price of electrolytic manganese.

Manganese is half the projected value of a hypothetical polymetallic nodule mine in the Clarion Clipperton Zone. I don’t see how that $2.3 billion revenue projection holds after the first year. Either the final product is not electrolytic manganese and that initial value of $1700 pet ton is off, or it is electrolytic manganese and it triggers a massive market surplus. Either way, I don’t see how the revenue projections for manganese hold.

Deep-sea mining has always been a high-risk, high-reward investment, but at this moment in time, I just can’t seem to make the math work.