The hot new thing on the internet is the latest revival of a centuries-old musical tradition. The humble sea shanty has taken the internet by storm, with remixes of remixes getting millions of views. The phenomenon written up in The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and CNN, and inspired an SNL skit.

As a marine biologist who learned to sing many of these songs to pass time on research vessels while honoring maritime traditions, I’ve loved watching this style of music spill all over my social media feeds, letting a new generation experience them. (Watch this man’s skepticism quickly fade to joy as he listens to Wellerman and tell me it’s not one of the purest things you’ve ever seen).

However, reading people’s explanations of why Sea Shanties are The Next Big Thing has made me realize something important: I didn’t know as much of the history of this style of music as I thought I did, and I’m not alone—much of the information contained in the articles I linked to above is oversimplified or even incorrect (Wellerman is a maritime song, but isn’t really a sea shanty, for one egregious example). As I began to ask around, I realized that there isn’t a single authoritative and thorough article about the history and culture of the sea shanty written for lay audiences anywhere on Al Gore’s internet. So I decided to dig into the literature, speak to experts, and write one myself. I hope you enjoy it!

What is a sea shanty?

“A sea shanty is a song used to coordinate work and effort, especially rhythmic effort, onboard ship,” Craig Edwards, the former director of the Mystic Seaport Music Festival, told me. Basically, the songs would allow sailors to know exactly when to pull on a line, or whatever task they were assigned, so they could do it all at the same time and therefore concentrate their force.”

One common task involved everyone pulling hard on a line all at once, which, if done correctly, would allow crews to get a second smaller pull in before they needed to reorganize and reset. The shanty “Blow the Man Down” is designed for coordinating such a task as everyone sings the lyrics together: “As I was a walking down paradise street, WAY [EVERYONE DOES THE FIRST BIG PULL] hey, BLOW [EVERYONE DOES A SECOND SMALLER PULL] the man down.” Edwards notes that even if a song tells a story, you stop singing it when the job is done even if the story isn’t done. And if you need to keep working, you can either start the song over or sing a different song designed for the same movement and effort and rhythm.

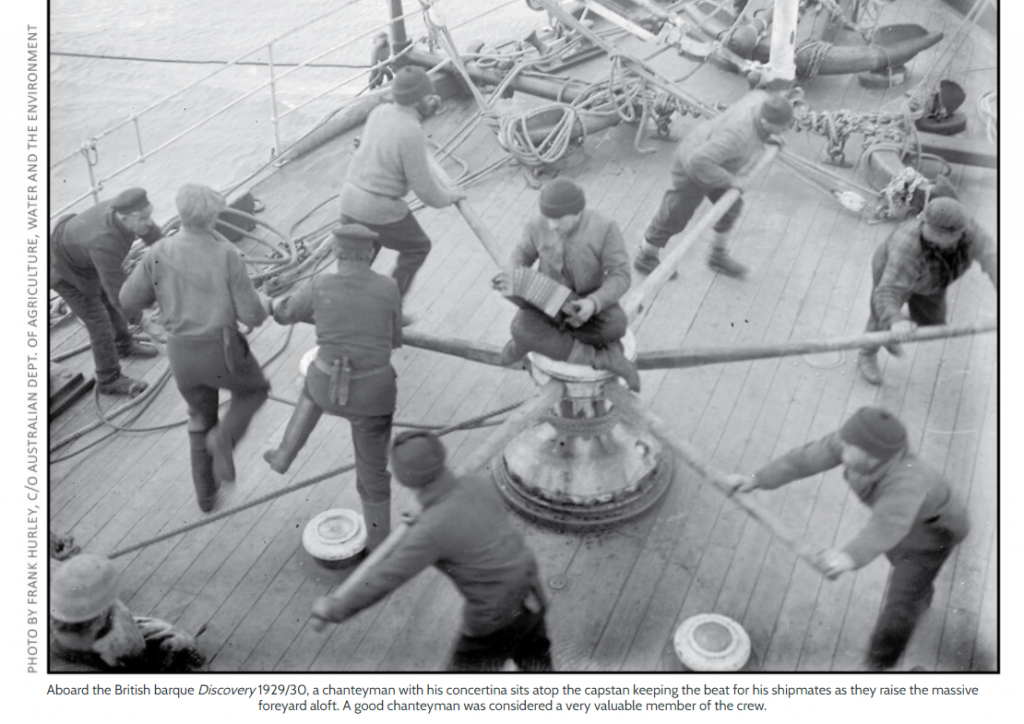

According to Dr. Jamie Goodall, a staff historian at the US Army Center for Military History, there were a few main types of shanties. “Short haul shanties were sung when tasks required rapid and quick pulls in a short amount of time. Halyard shanties, or long-drag shanties, were used for heavier work that required more setup time between pulls. Capstan shanties were used for long, repetitive tasks that required a sustained rhythm. The songs had to be simple melodically and lyrically in order to keep everyone on beat and in sync.”

A key element of Shanties is the call and response format, Chris Koldeway, a music teacher who worked with Mystic Seaport’s Chantey staff, told me. “This means that a solo singer sings verses, and the response is a full chorus or short refrain from the crew,” he said.

“Sea shanties make hard work easier, sometimes just by distracting from a repetitive job, but also by allowing a small group of workers to time their work to the rhythm of the job,” Mary Mallory, who taught in the Sea Semester program for 25 years. “You could just do that same thing by saying ‘ok everybody, 1, 2, 3, HAUL!’ but a song is nicer.”

In recent years, the term has been used colloquially to refer to any song about sailing or maritime life. “Most people use ‘sea chantey’ to refer to any song that has nautical or maritime vibes,” Dr. Joe Maurer, a teaching fellow in the Humanities at the University of Chicago told me. “Academics and folk revivalists will insist that these songs are not shanties, and they’re correct technically, but this is the broadly public accepted meaning of the term. It’s important to distinguish the technical definition from the colloquial definition even if you accept both as valid as I do.”

The sea shanty has its roots in West African worksong

Craig Edwards notes that in European history, most heavy lifting involved draft animals, and there weren’t songs for workers moving heavy slabs of stone to build cathedrals and castles because it was horses and mules doing much of that stuff. But these sorts of “worksongs” were very commonly used among many cultures in Sub-Saharan West Africa.

“Work song means a song sung while actually performing labor, as opposed to an ‘occupational song,’ which is a broader category that also includes songs about work or a particular working community,” Steven Winick, a specialist at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, told me. He notes that “Wellerman” is a sea song, a song about sailors, but not a song used to coordinate work about ship, and therefore not technically a sea shanty! He also notes that whaling vessels rarely used worksongs, because the act of whaling required so many people to help that worksongs coordinating effort was rarely needed.

Mary Mallory told me that these songs traveled with enslaved people to the Caribbean, where they became incorporated with work onboard ships. And as Black crews worked alongside white crews, it resulted in an amalgamation, with Anglo and Irish lyrics put to African rhythms. Craig Edwards notes that this resulted in a nationalistic myth, spread by British folklorist Cecil Sharpe, that shanties must be a long-standing English tradition. Rachel Elliott, the education director of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, told me that the historical role of Black sailors has not always been appropriately understood and valued.

Lately, there’s no doubt that African musical tradition was a major influence on sea shanties. And despite some criticism of whitewashing the history of shanties, “there has never been any real question that Black people were central to the development of this musical style,” Stephen Winick said. “Scholars have been arguing against this wrong impression, and for the central importance of Africans and African-Americans, for over 100 years.”

Dr. Gibb Schreffler of Pomona College’s Department of Music says that though sea shanties have a particular historical romanticization to them, this whole genre of music took place far more frequently on land than at sea. “We need to stop thinking about the sea and sailors to know chanties,” he told me. “One has to accept that the place of performance (sea) doesn’t define the genre. The same songs, and many more like them, were sung much more often in contexts outside of ships. Understand that there are comparatively few times during a sailing voyage to be singing chanties—keeping in mind that chanties aboard ships were sung with only certain work tasks. By contrasts, the people on shore singing these songs at their labor were doing so effectively all day.”

Dr. Schreffler noted that despite a sometimes-held (and false) aura of whiteness surrounding sea shanties, this isn’t really a case of cultural appropriation. “Non-Black singers in the historical period acculturated into chanty singing,” he told me. “It was not a case of stealing something and taking credit for it, but rather of white laborers assimilating into a cultural practice established by Black laborers.”

Indeed, Black sailors were common in the early United States. “Work as a sailor was especially appealing for free African-Americans,” Roger Bailey, a professor of history at the US Naval Academy, told me. “As many as 1/5 of sailors in the early 1800s were Black. There was still racism, but the ship’s hierarchy placed black men on more even footing than they would have enjoyed on land. Plus, as a sailor you could learn a skilled trade and eventually make relatively good pay compared to the limited opportunities available ashore to black men. The whaling industry in particular placed a premium on a sailor’s skill at hunting whales, so it wasn’t uncommon to see talented African Americans, Native Americans, and Pacific Islanders serving as mates and petty officers aboard whalers. All this is to say that current and former slaves were an integral part of the maritime community, and there’s no doubt that African Americans were a major influence on sea shanties.”

When were sea shanties used?

To understand the cultural context of the sea shanty, it’s important to know the history of modern maritime exploration.

“1492 was the beginning of a paradigm shift in the use of maritime power in world history, with European maritime nations fanning out across the world to establish colonies and trade routes, causing wealth to flow across the face of the world at an exponentially greater rate than ever before,” Craig Edwards told me. “That movement of wealth attracted a great amount of violence, with predictable technological and political and policy responses, and by the 1550’s a typical English merchant ship looked a lot like a warship in important structural elements, including cannon and supports for them. The need to maneuver the ship while also loading aiming and firing the cannons required a big crew.”

During this time in maritime history, the risk of getting into a shootout with a hostile vessel from a foreign competitor was omni-present. Because of this, Edwards told me, large merchant crews often followed the naval tradition of working quietly just in case a lookout needed to be able to get everyone’s attention in a hurry, which lasted for centuries, until approximately the end of the Napoleonic wars around 1815. After that, the risk of a deadly encounter at sea went way down, and ships began to focus on speed and profit.

“To save money, merchant vessels hired fewer sailors,” Edwards said. “There were formulas for the minimum number of men needed on a merchant ship to operate safely.” Some ships went from having 100 men or more per watch to just 20 men per watch, and “with smaller crews, coordination of muscle and effort, and concentration of force, becomes much more important. Shanties didn’t work well for the rhythm of shipboard tasks with larger crews, but they work great for work like this, when you have to move the same amount of weight with fewer people!”

Shanty, shantey, or chanty? The experts I spoke to used a variety of different spellings, sometimes interchangeably, sometimes to refer to different time periods in the development of this musical genre. A Washingtonian article noted that technically “the correct way to spell the name of these tunes is sea chanteys, not shanties.”

Sea Shanties today

After World War 2, carrying cargo by sail was essentially nonexistent, according to Craig Edwards. But with the rise of “sail training,” teaching people who use far more high tech vessels how ships used to operate, came a revival of sea shanties. “When you go on board these vessels now, if you hear shanties, it’s with crews who sing them off duty but never use them at work,” he said. “For everyone on the modern-day sailing vessels, there’s skepticism that these songs were ever used to coordinate work, because the way they do things now doesn’t need this kind of coordination.”

Nowadays with the Mystic Sea Shanty Festival, Edwards said, “all of a sudden there’s a big crowd of people, and somebody sings out a line, and the whole crowd joins in, and after the concerts we’d retire to local pubs and people would drink beer and sing, and anyone who wanted to sing could start a song and everyone would join in!” He notes that a maritime music festival he attended in France a few years ago had millions of attendees, and that one of the world’s largest festivals is held every year in Krakow because of the role of a 1970s sea shanty resurgence in protesting harsh Soviet rule.

(And don’t forget the central role of sea shanties in “Assassin’s Creed: Black Flag!”)

What do experts think of the Sea Shanty moment we find ourselves in?

“Every generation of kids should be enchanted with shanties,” Stephen Winick said. “But I’ll speculate that as the pandemic pushed more and more of our social lives online, people with musical talent were looking for ways to collaborate without being in the same room, and TikTok offers a nice platform than that. Additionally, group singing is something that lots of folks can do even without technical skills, instruments, or musical training, and they require less harmony than barbershop quarter singing, and less religious zeal than spirituals. Updating the songs to be palatable to their friends and modern audiences is honoring the traditions.”

“Group singing is terrific,” Mary Mallory said, “and there are too few opportunities for people to engage in it today outside of church. My college students loved to sing together on Sea Semester ships. The online community embracing it through TikTok answers a basic human need to sing, and to sing together.”

“We’ve been so excited to see the enthusiasm for sea shanties that has exploded into the public consciousness,” Rachel Elliott told me. “Everyone engaging with these traditions, and making them their own, is contributing to keep the flames of tradition alive by making it relevant to modern life. Sea shanties are an excellent way into folk songs and music more generally.”

“I firmly believe that these TikTokers are honoring the tradition,” Joe Maurer said. “This is the 21st century version of the folk music process! These renditions are quite different from the shanty singers of the past generation, but I think that’s fine and good. They’re making it their own, which is what will allow this fun and fascinating musical tradition to continue!”

Maurer also had a theory as to why this is happening now. “There is something suggestive about peoples’ desire for a simpler life, like a lumberjack or a sailor,” he said. “This fasciatnion speaks to the complexity and dismal nature of modern life. The appeal of another life and another world grows as one’s own world seems to offer less possibility. Folk revivals are always about a fantasy of the past, and the symbolic weight of that fantasy shifts in response to anxieties of the present.”

“It’s wonderful because the enthusiasm is there, there’s so much participation and enjoyment,” Chris Koldeway said. “Music and culture is a living, breathing thing, with constant change and flux. These songs have a connection to the folks who came before we did. We can make connections to our past and help to inform our future. So go out there, find others to sing with, and have a great time!”

FURTHER READING

African-Americans in the Maritime Trades

Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail

Black Sailors and Sea Shanties

Boxing the Compass by Gibb Schreffler

An Introduction to English Sea Songs and Shanties

TikTok’s sea chanteys – how life under the pandemic has mirrored months at sea

A 3 hour playlist of sea shanties and maritime songs on Spotify