As in-person negotiations on the future of exploitation in the deep ocean resume this week in Kingston Jamaica, we reflect back on the last two years of development as reported on our sister site, the Deep-sea Mining Observer. This article first appeared on May 22, 2020.

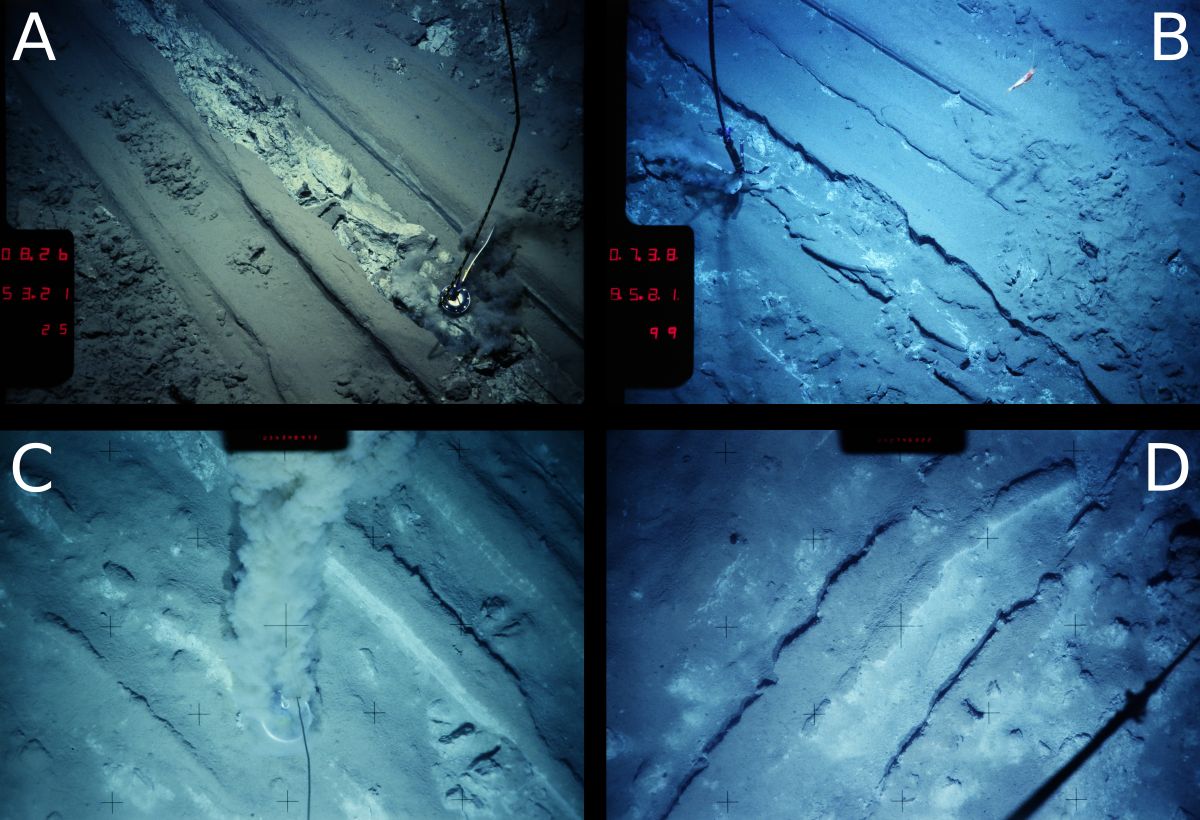

In the late 1980s, as the first wave of deep-sea mining exploration approached a decade of hibernation, researchers launched an ambitious experiment to understand the long-term environmental impact of harvesting polymetallic nodules from the abyssal plain. The Disturbance and recolonization experiment in a manganese nodule area of the deep South Pacific (DISCOL) remains the most ambitious attempt to understand how nodule extraction affects deep ocean ecosystems. Though interest (and funding) waxed and waned with the prevailing interest in deep-sea mining, now, more than 30 years later, DISCOL provides the only large, multi-decade impact study from which contractors, regulators, and environmental advocacy groups can draw inferences about the recovery and resilience of deep-sea ecosystems following mining-induced disturbances throughout the lifetime of an ISA-issued mining exploration or exploitation lease.

The 1980s saw a surge in interest for deep-sea mining. The successful early campaigns of the late 1970s, bolstered by CIA funding for Project Azorian, presented a future of seemingly limitless profit scattered across the seafloor. That the early financial projections were supported by covert government funding was not yet widely known, and, even for those who were privy to the operation, regardless of initial funding the value had been established, the ship built, the technology sea-trialed. The profit potential was there. What was still tabula rasa was the environmental consequences of extraction on an almost completely unknown ecosystem.