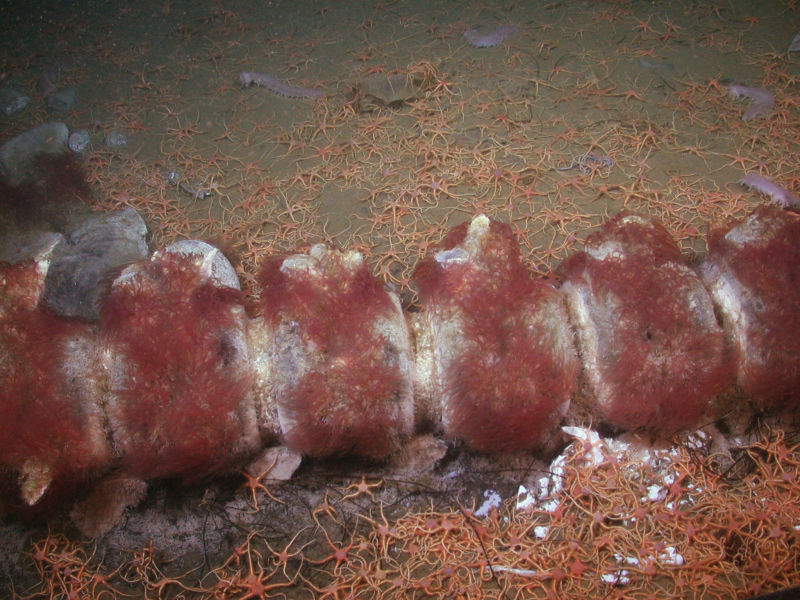

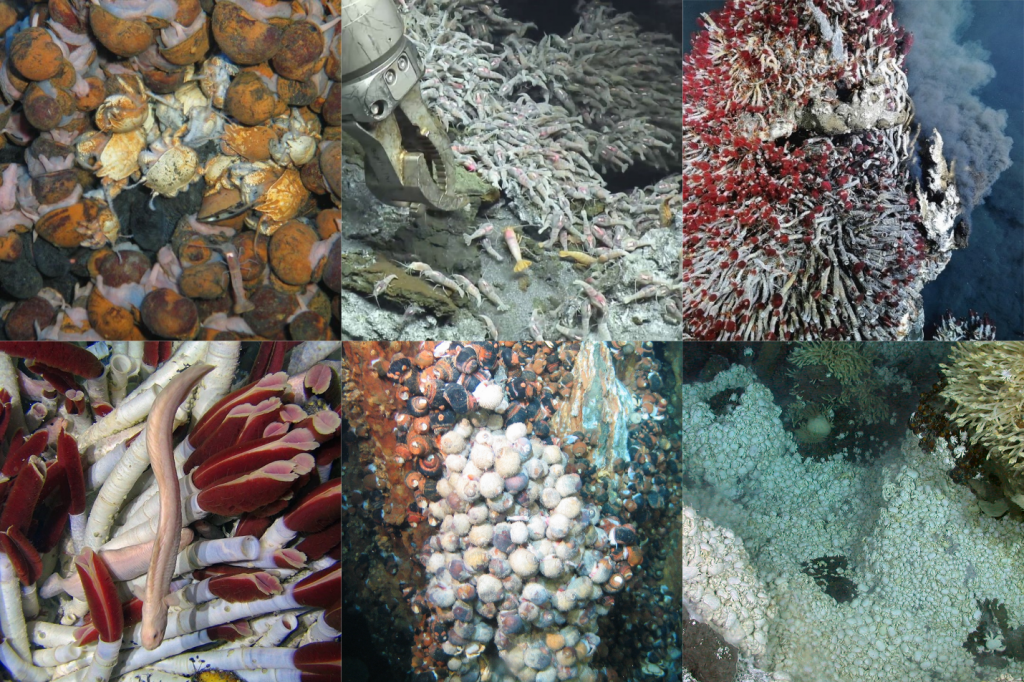

“When the RV Knorr set sail for the Galapagos Rift in 1977, the geologists aboard eagerly anticipated observing a deep-sea hydrothermal vent field for the first time. What they did not expect to find was life—abundant and unlike anything ever seen before. A series of dives aboard the HOV Alvin during that expedition revealed not only deep-sea hydrothermal vents but fields of clams and the towering, bright red tubeworms that would become icons of the deep sea. So unexpected was the discovery of these vibrant ecosystems that the ship carried no biological preservatives. The first specimens from the vent field that would soon be named “Garden of Eden” were fixed in vodka from the scientists’ private reserves.”

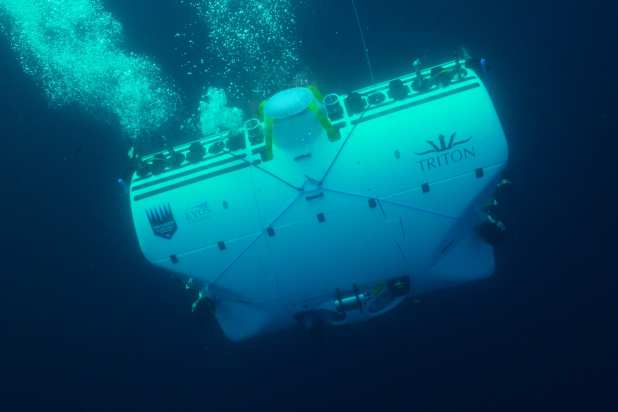

Thaler and Amon 2019

In the forty years since that first discovery, hundreds of research expedition ventured into the deep oceans to study and understand the ecology of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. In doing so, they discovered thousands of new species, unraveled the secrets of chemosynthesis, and fundamentally altered our understanding of what it means to be alive on this planet. Now, as deep-sea mining crawls slowly towards production, we must transform those discoveries into conservation and management principles to safeguard the diversity and resilience of life in the deep sea.

Though research at hydrothermal vents looms large in the disciplines of deep-sea science, relative to almost any terrestrial system, they are practically unexplored. Over the last 2 years, Drs. Andrew Thaler and Diva Amon have poured through every available cruise report that made a biological observation at the deep-sea hydrothermal vent to assess how disproportionate research effort shapes or perception of hydrothermal vent ecosystems and impacts how we make management decisions in the wake of a new form of anthropogenic disturbance.