Transcript available below.

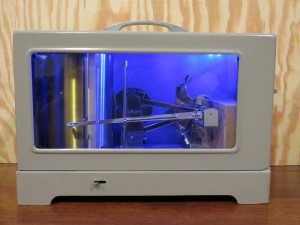

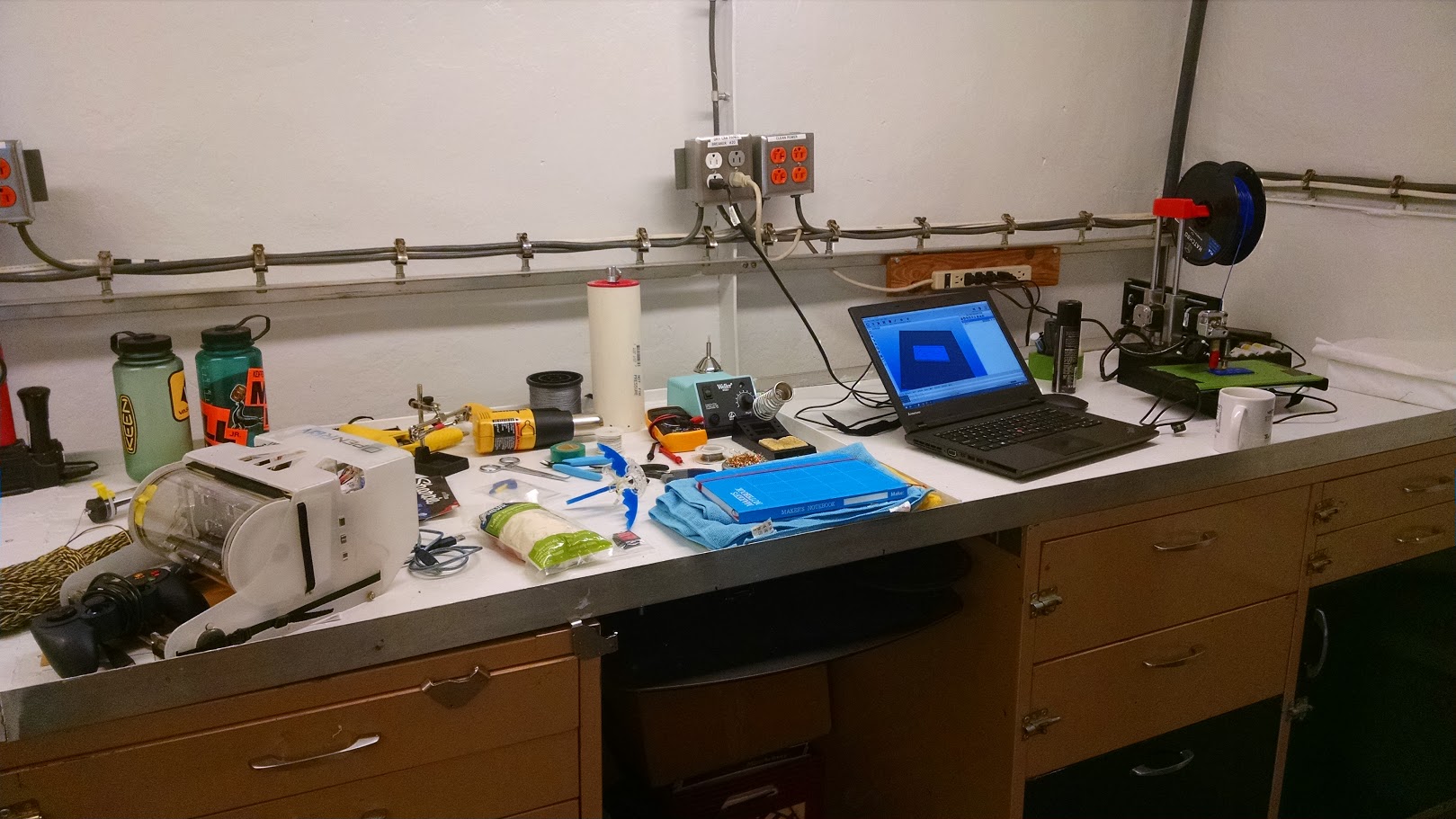

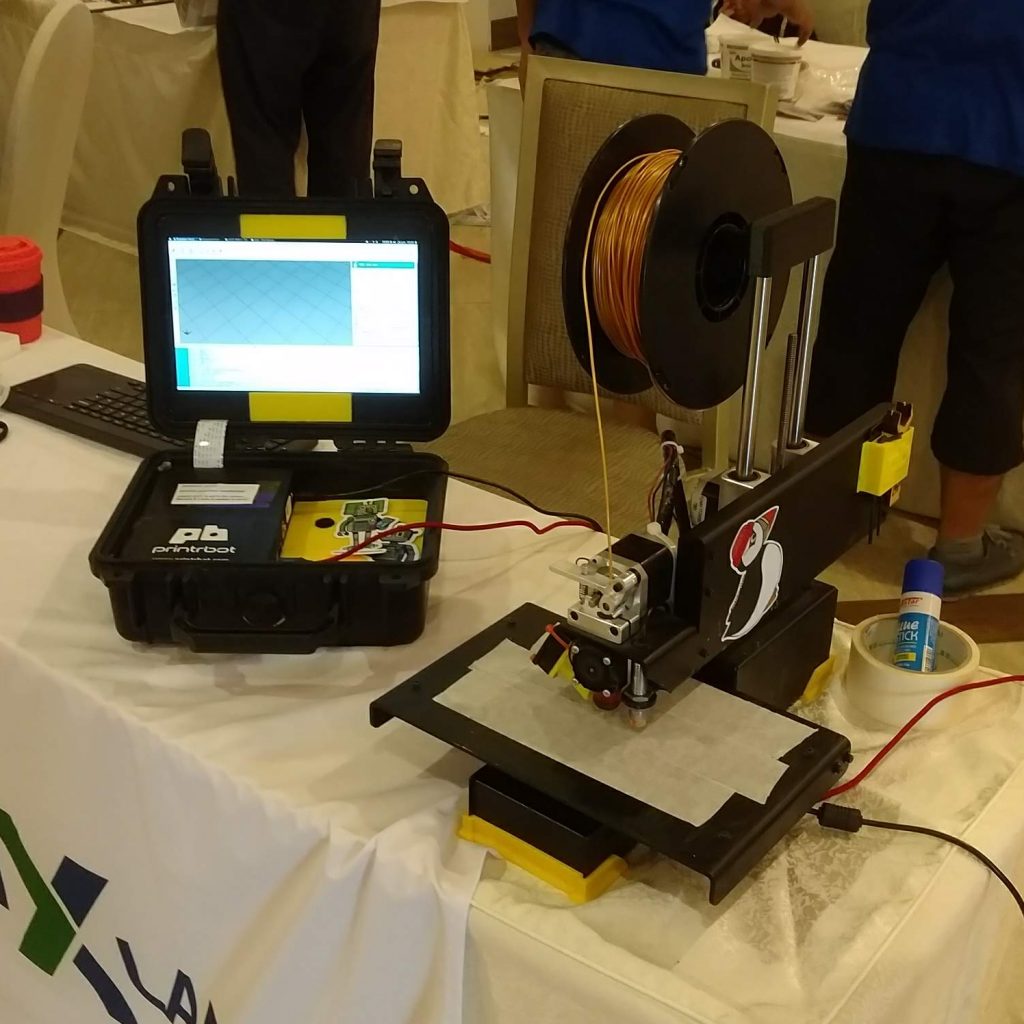

At the beginning of 2024, I made a commitment to make it the year of the OpenCTD. A CTD is an oceanographic instrument that measures salinity, temperature, and depth. It is an essential tool in the conduct and marine scientific research. Access to CTDs often present a barrier to communities and knowledge seekers interested in … Read More “Open-source science hardware for an Open Ocean: Reflecting on the Year of the OpenCTD” »

One-hundred-fifty meters hardly seems like anything at all.

One-hundred-fifty meters hardly seems like anything at all.