Political ecology within the First World came from a gradual realization that the definition of the field did not only apply to exotic cultures abroad, but had resonance domestically. As first defined by Blaikie and Brookfield (1987), political ecology combines “the concerns of ecology and a broadly defined political economy. Together this encompasses the constantly shifting dialectic between society and land-based resources, and also within classes and groups within society itself” (17). Scholars returning from research in the Third World observed this shifting dialectic in their own countries, complete with struggles over power and access between sectors of society.

Political ecology within the First World came from a gradual realization that the definition of the field did not only apply to exotic cultures abroad, but had resonance domestically. As first defined by Blaikie and Brookfield (1987), political ecology combines “the concerns of ecology and a broadly defined political economy. Together this encompasses the constantly shifting dialectic between society and land-based resources, and also within classes and groups within society itself” (17). Scholars returning from research in the Third World observed this shifting dialectic in their own countries, complete with struggles over power and access between sectors of society.

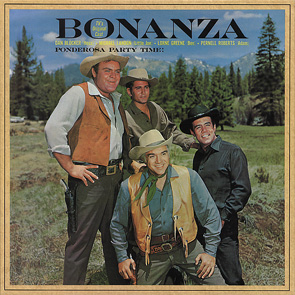

The first call to the political ecology community to consider applying their principles to the First World came from Louise Fortmann (1996) in her article “Bonanza! The unasked questions: Domestic land tenure through international lenses.” Although she admitted there are vast differences between home and abroad, she identifies six lessons from the international land tenure debate that could have traction in the United States: property as social process, customary tenures, common property and community management of resources, gender, the complexity of tenancy relationships, and land concentration.

Read More “Political Ecology at Home – Lessons from Abroad?” »