Tangier Island is sinking.

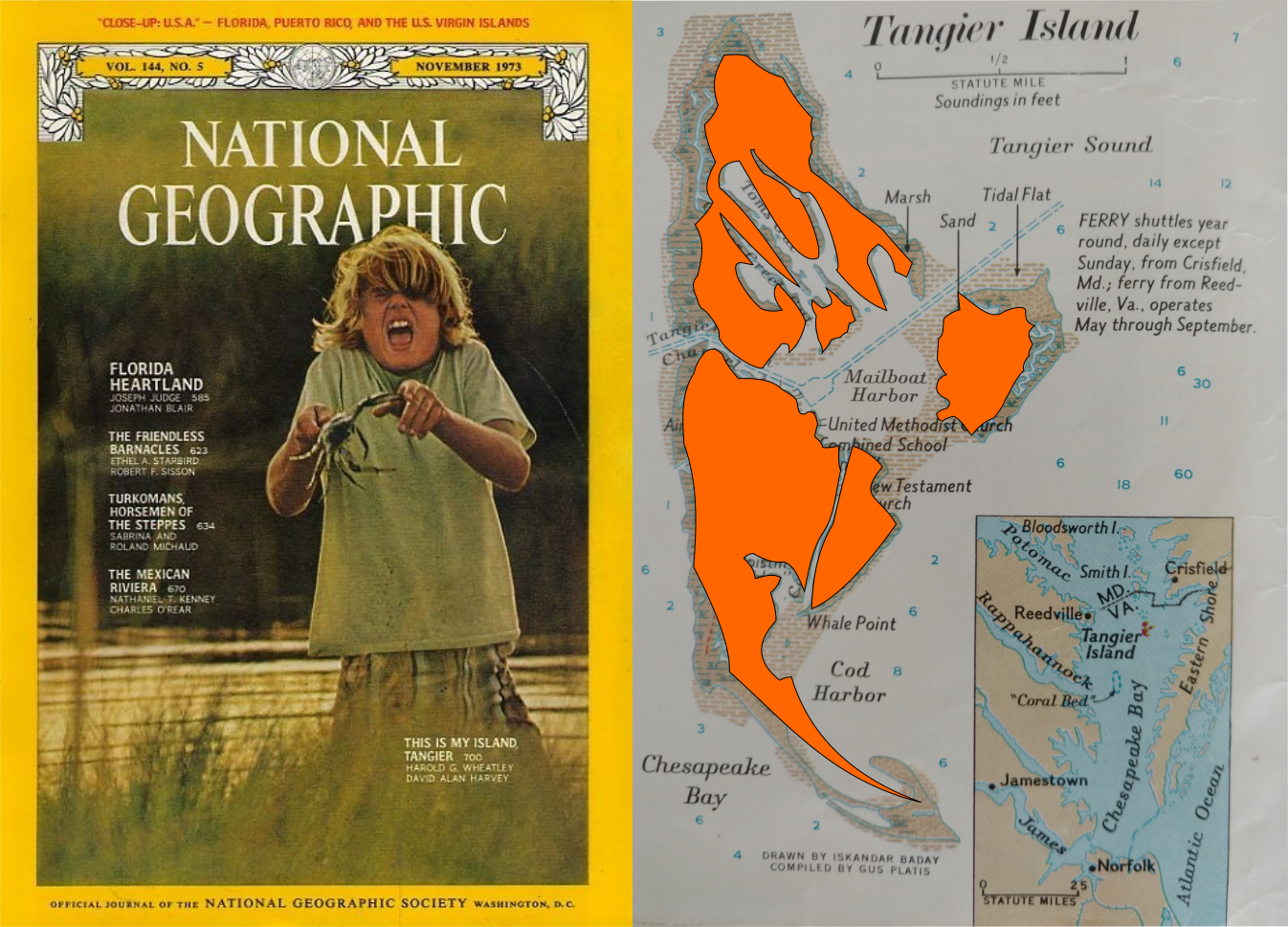

The last inhabited island on the Virginia side of the Chesapeake Bay covers barely 740 acres of marsh and sand, 1/3 of the area it had when it was first mapped in the 1850s. Tangier suffers from the dual onslaught of erosion and sea level rise. In a good year, the island loses 7 to 9 acres of land, while the westernmost beach recedes 4 meters, exposing homes, gardens, and even graves to the Chesapeake’s unrelenting waves. The town, situated on three sandy ridges, rises to a high point just 1.2 meters above sea level. As salt water incursion and erosion deplete trees and other vegetation, erosion will increase. With a conservative projection of mean sea level rise of 4.4 millimeters per year for the southern Chesapeake Bay, the highest point in town, if it manages to stave off the inexorable erosion, would be completely underwater in 270 years. Tangier will be uninhabitable centuries before that.

The Chesapeake Bay and mid-Atlantic coastlines are hot spots for climate change, expecting greater than average sea level rise and more frequent and intense storms. Though the residents of the conservative community on tangier are skeptical, the evidence for human-induced climate change’s impact on the island and the effect of sea level rise is undeniable. Intensifying storms and more dramatic temperature shifts have and will continue to exacerbate erosion. Many residents believe that, had Hurricane Sandy made landfall over the Chesapeake Bay, rather than further north, Tangier would already be largely abandoned. Even the glancing blow from Sandy left significant damage in its wake.

One big storm could spell the end for this 350-year-old community.

- Schulte and friends (2015) Climate Change and the Evolution and Fate of the Tangier Islands of Chesapeake Bay, USA. DOI: 10.1038/srep17890.

Tangier is a crabbing town.

One could argue that Tangier is the crabbing town. Despite its small size, Tangier is home to the most valuable blue crab fishery in the Chesapeake Bay. Until recently, crabbing, and other fisheries, were the island’s sole source of income. Now, many residents spend weeks away, working tugboats and other maritime trades. Tourism now plays an increasingly important role in the community, with ferries from the Maryland and Virginia mainlands visiting daily.

Amy and I had the pleasure of visiting Tangier for a weekend last month (head over to my Facebook page for more photos a 360 images of the trip). Too small for most cars, islanders commute across the island in golf carts and ATVs. With barely 450 residents (and that’s an optimistic estimate), the island still felt busy. More than once we had to duck out of the way of a speeding golf cart. There were more than enough restaurants for the small group of tourists that disembarked with us, and the 50s-style ice cream shop was lively on that hot Sunday afternoon. The public beach, though smaller than it once was, still offers expansive views of the sometimes rough Chesapeake Bay.

Famously, town residents speak a unique Cornish dialect which hearkens back to the earliest settler days.

All of which is to say that Tangier is a town. Unlike some of the communities I’ve worked in, which are comprised of just a few dozen hold-outs in what are, essentially, abandoned townships, Tangier still has a strong, multi-generational community with enough children to support a school on-island. Were it not so isolated from the mainland, there would be no debate about protecting its waterfront.

Tangier has an ambitious plan to protect its shoreline: a massive seawall.

The $20 to $30 million seawall would armor the Uppards, the extension of Tangier that provides the bulk of the island’s protection against storms. The Uppards once housed an offshoot of the main town, now it’s unoccupied. Once the Uppards goes, there will be little to protect Tangier from further erosion, leading to even faster loss of the little remaining land. But not all Virginian’s see the value in saving the island or its community, with some arguing that any seawall would just be delaying the inevitable and taxpayer money is better spent helping Tangier’s residents relocate. Despite erratic promises from the federal government, Tangier’s seawall remains in limbo. The longer it takes to build a seawall, the less of Tangier will be left to protect. A much smaller project to reinforce the main harbor is progressing, but residents acknowledge that without protection for the Uppards, the jetty will be ultimately ineffective.

Beyond sand loss or sea level rise, whether or not a seawall is ever built, Tangier suffers from an entirely more fatal form of erosion. As we traveled through the small town, talking with residents and watching the numerous documentaries featured in the Tangier History Museum and on “Tangier TV” at Four Brother’s Crab House, one consistent theme kept rising to the surface: “There are no opportunities for women, here.” Tangier is a town built by watermen. Crabbing on Tangier is a career that only men pursue. The few limited options for careers for women include the post office, the school, and the few restaurants, inns, and other outlets for seasonal tourism. Young women who leave for college discover that the mainland offers far more opportunity.

Comments on work opportunities for women begins at 14:42.

In Drawdown, perhaps the most comprehensive publication to discuss solutions to climate change, the authors list educating women and girls as one of the single most significant steps that can be taken to limit the effects of global warming. Opportunity breeds innovation, and allowing all citizens to fully participate in a community has profound, far reaching impacts. In my travels throughout the world, I’ve found this to be just as true for community resilience as it is for environmental resilience.

In the details, Tangier Island is unique, but it is also very much like many small, isolated fishing communities from North Carolina to Papua New Guinea to Rota to the Faroes. As access to both information and travel increases, those who feel that their island has few opportunities for them will leave. If, as we heard consistently from residents on island and in clips chosen to represent the island’s way of life in both internally and externally produced documentaries, the young women of Tangier feel that the island offers them few opportunities, they will leave. Long before erosion and sea level rise returns Tangier to the Chesapeake Bay, the community will fade.

Against that, no seawall can hold.

Tangier is the traditional hunting ground of the Pokomoke people, who were driven from their territory by disease, ethnic cleansing, and forced displacement by the federal government.

Hey Team Ocean! Southern Fried Science is entirely supported by contributions from our readers. Head over to Patreon to help keep our servers running and fund new and novel ocean outreach projects. Even a dollar or two a month will go a long way towards keeping our website online and producing the high-quality marine science and conservation content you love.