A curious vessel sits atop a few struts in the Barcelona harbor. Passing tourists could be forgiven if they thought the small, wooden craft was a prop from the golden age of film or a quiet monument to the work of Jules Verne. It is neither. This ship, built from olive wood and clad in copper, is perhaps the most remarkable seagoing vessel of its time. She is Ictíneo II, the first true submarine.

Narcís Monturiol i Estarriol was a Catalonian revolutionary, utopian iconoclast, and proto-feminist writer who argued that the government, rather than the church, should oversee marriage licenses. He founded several newspapers–which were often shut down after a few issues–including La Madre de Familia “to defend women from the tyranny of men” and Spain’s first communist newspaper, La Fraternidad.

After temporary exile in 1848, he returned to Spain, under the condition that he retire from publishing.

And so, this accidental aquanaut turned his eyes to the sea.

It was with a keen eye towards the plight of the worker that Monturiol focused his attention on the coral harvesting industry. After witnessing divers face sharks attacks, become entangled in coral, and drown, he committed himself to building a self-contained machine that would allow men to dive to great depths safely. In September 1859, after several years of fundraising, research, and experimentation, Ictíneo I made her first dive in Barcelona harbor.

The silence that accompanies the dives; the gradual absence of sunlight; the great mass of water, which sight pierces with difficulty; the pallor that light gives to the faces; the lessening movement in the Ictíneo; the fish that pass before the portholes—all this contributes to the excitement of the imaginative faculties. . . . there are times when nothing can be seen outside by natural light, when one sees nothing but the obscurity of the deep; all noise and movement stops; it seems as though nature is dead, and the Ictíneo is a tomb.

Narcís Monturiol i Estarriol. source.

Ictíneo I was sleek and capable, but she still depended on human muscles to power her through the water. Her oxygen supply was limited. After more than 50 dives, the poor submarine was wrecked when a freighter collide with the berthed vessel.

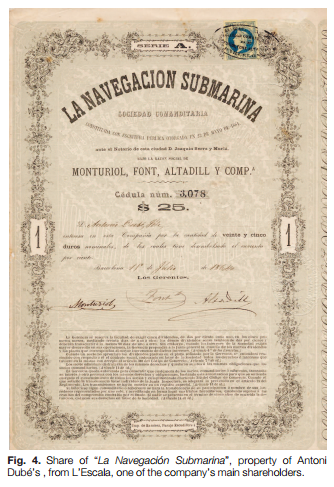

Buoyed by the success and popularity of the project, Monturiol went to work on the second iteration of his submarine. Unfortunately, the Spanish government was unwilling to fund his project, so he turned to a model that would not have a name for another 150 years. He crowdfunded it. In a “letter to the nation” he implored the people of Spain and Cuba to contribute a few pesetas towards the new submarine. He raised 300,000 pesetas, the equivalent of over $3.5 million today. With that influx of crowdfunded cash, Monturiol founded La Navegación Submarina and began work on the Ictíneo II.

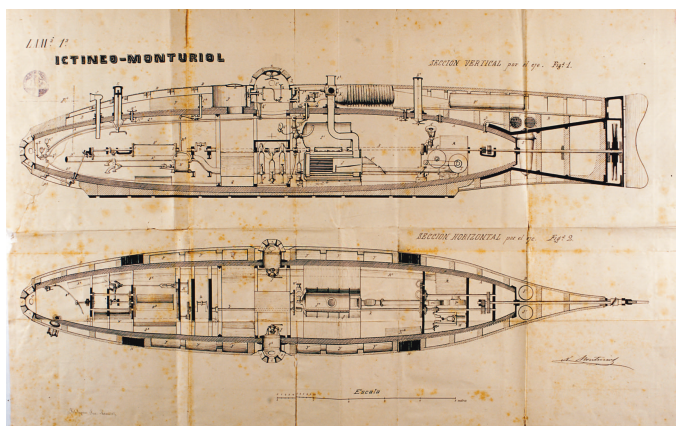

It’s nearly impossible to describe how huge a technological leap forward the Ictíneo II was. She was the first submarine with a double hull, the first with a self-contained air system, the first with wedge-shaped portholes that used the pressure of water to make their seals tights. But, most astonishingly, was her engine.

Ictíneo II used a steam engine unlike any steam engine used before. A submarine couldn’t burn wood or coal like a conventional boiler, the fire would consume precious oxygen. Instead, Monturiol unraveled the chemical reaction that turns manganese dioxide, potassium chlorate, and zinc into heat and oxygen. As long as her engines were fueled, Ictíneo II would not run out of air.

Unlike their American contemporary, the Hunley, the Ictíneos had a perfect safety record. The first dove over 50 times with no incident, succumbing to her briny fate while docked, thanks to an inattentive freighter captain. The second met a less dignified end. After several dozen dives, Monturiol found himself and his company bankrupt. His creditors stripped the most advanced underwater vehicle of her time for parts. The motor went to a textile factory. The portholes would adorn the shipbreaker’s bathroom.

Monturiol published his magnum opus, Ensayo sobre el arte de navegar por debajo del agua, Essay on the Art of Navigating Under Water, the first manual on submarine construction and operation, posthumously.

I find Monturiol’s story fascinating, not only for the technological contributions that he made, but also for the seeming contradictions of his life: from Utopian idealist to would-be arms merchant. In his final attempts to save the Ictineo II, he courted governments (first Spain, and then the US) with the military potential of his invention, demonstrating its stealthy ability to deliver cannon fire while submerged – but they were not interested at the time. An attempt to switch from Kickstarter to DARPA, perhaps?

(And reflecting on that apparent journey in Monturiol’s life, I can’t help pondering how many of the later advances in deep-submergence technology in the 20th century, which have now given us scientific access to “the common heritage of mankind”, were nurtured by a Cold War environment of military competition).

Agreed.

Though reading about his early life as a violent revolutionary, followed by his transition to pacifism, I see it more of a pragmatist picking the most effective tactics. I don’t get the impression he was ever, truly a “pacifist” but rather a very savvy political strategist reading the field.

WOW! Just wow!! What a fascinating story… impressive. Thanks Andrew.

That was really interesting. Thank You!