This is the first entry in Crowdsourcing ConGen. This entry is meant to be half of an Introduction which lays out the framework for what conservation genetics is, its philosophical basis in population genetics, and why it’s a meaningful method of inquiry for conservation. This first section is meant to outline foundational concepts in population genetics. It is not meant to be a detailed summery of population genetics, but needs to be accurate and clear.

This is the first entry in Crowdsourcing ConGen. This entry is meant to be half of an Introduction which lays out the framework for what conservation genetics is, its philosophical basis in population genetics, and why it’s a meaningful method of inquiry for conservation. This first section is meant to outline foundational concepts in population genetics. It is not meant to be a detailed summery of population genetics, but needs to be accurate and clear.

There is often a functional gap present in our understanding of the interaction between organism, ecosystem, and evolution. Organismal biology uncovers the life history of the organism, its physiology, and behavior. Ecology explains how organisms interact with each other, with predators, prey, and parasites, and maps the web which connects individuals to an ecosystem. Evolution reveals the deep history of life on earth, where species came from, how they are related, and how they’ve adapted to their environment. Between the organism and the ecosystem, where ecology merges with evolution, we find the population. Understanding the distribution of populations, where and how boundaries form between them, and historical patterns of colonization, migration, and isolation is crucial for determining the underlying ecologic and evolutionary processes which guide wise conservation initiatives.

Population genetics is the study of variation in the distribution of allele frequencies that occurs as groups of organisms from the same species separate from each other in space or time. The alleles chosen for population genetics studies are selectively neutral – they occur in non-coding regions of a genome and are not affected by natural selection. Under ideal circumstances, these alleles associate randomly within a population and are not linked to each other, or to coding regions of the genome. Alleles are not distributed evenly across all populations. Because each population has a different set of alleles that occur in different ratios, the distribution of alleles within a group of individual organisms can be used to define discrete populations and determine the extent of interbreeding that occurs among them.

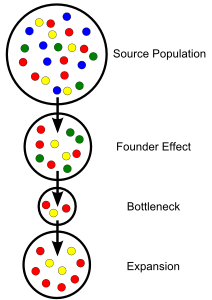

Several processes determine how allele frequencies within separate populations differentiate. Conceptually, the simplest way for allele frequencies to diverge is through mutation. New alleles that arise in a population after it has become isolated will only occur in that population. Founder and bottleneck events can also create variation in allele frequencies. A population that has been founded by a small group of individuals isolated from a larger (or more diverse) population may not possess all the alleles that occur in the source population. Likewise, if an isolated population experiences a large decline in numbers, less common alleles may be completely removed from that population, resulting in a reduction in total genetic diversity and a shift in allele ratios.

Genetic drift is a more subtle way for large changes in allele distributions to occur. Two populations which become isolated from each other may begin with the same allele distributions, but because alleles associate randomly and mating is random with respect to those alleles, random changes in allele frequencies will accumulate with each new generation. This accumulation is independent of other populations. Both populations may have the exact same alleles but in completely different ratios. Eventually, drift will cause some alleles to become fixed (they occur in all members of the population), while others disappear.

By examining these patterns of allele distribution, population geneticist can unlock the deep demographic history of a species. Historical patterns of expansion and contraction, migration and colonization, isolation and ultimately speciation, can be uncovered through examining the genetic changes that accumulate in populations.

Any comments regard substance or style are appreciated.

~Southern Fried Scientist

I really like the topic, and am eagerly awaiting additional entries. I’m happy that you don’t include in-text citations as they can be distracting, but it would be nice if you recommend books/papers/etc… at the end for those of us who want to read more or refresh our memories on the ideas and terms that you use.

I’ll have a recommended reading at the end of each section, as well as an executive summery.

As a former population and conservation geneticist, I sincerely appreciate your efforts in trying to communicate the importance of the field to non-technical audiences. As you point out, policy makers and managers need to have a solid understanding of the importance of genetic information in making conservation and management decisions. Explaining some of the basics of the science should lead to more effective management.

As you think about this project, I’d encourage you to think hard about the specific audience for the piece. Policy makers, managers, and the general public come in a variety of flavors. If you want to speak to congressmen, their staff and/or the general public, your focus will probably need to be more general and should ultimately focus on specific examples and results. You will have to justify ideas that are self explanatory for the trained geneticist (e.g. maximizing genetic diversity is beneficial for species survival). If you aim to affect federal agency managers, you will want to think about what level you are targeting (political appointees, agency scientists?) and dial in your language appropriately.

Especially for an introduction, I would make this as broadly applicable and understandable as possible, so that it might be useful to a wide audience. You might think about questions like “What makes genetics important for conservation?” “What are some common species where genetics has informed or should inform conservation? What were the outcomes?” “Why do we even care if specific species go extinct?” Once you put the field in the broad, society level concept, then you might narrow in on the concepts that inform conservation genetics.

I look forward to reading more of your posts.