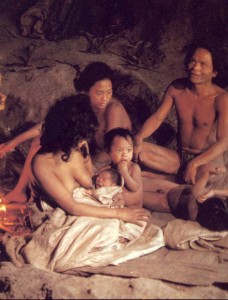

In 1971, a group of people known as the Tasaday were discovered on a remote island of the Phillipines known as Mindanao. They wore leafy loincloths and subsisted off what the forest could provide, possessing no knowledge of tobacco, corn, rice, or domesticated animals. They spoke a new dialect of Malay-Philipino language that included no word for outsiders, war, weapon, or enemy, giving them the title ‘The Gentle Tasaday’. The family unit was nuclear and the community has no formal organization or government outside of some loose food-sharing networks.

In 1971, a group of people known as the Tasaday were discovered on a remote island of the Phillipines known as Mindanao. They wore leafy loincloths and subsisted off what the forest could provide, possessing no knowledge of tobacco, corn, rice, or domesticated animals. They spoke a new dialect of Malay-Philipino language that included no word for outsiders, war, weapon, or enemy, giving them the title ‘The Gentle Tasaday’. The family unit was nuclear and the community has no formal organization or government outside of some loose food-sharing networks.

Today, Tasaday life is way different and matches more modern tribal life in the Phillipines, as documented on their website. The question is, however, whether this modernization was normal development post-contact or whether there was a hoax involved.

A hunter named Dafal first discovered the tribe while trapping with his father. He returned, leading Philipino official Manuel Elizalde, Jr, where they were met by 26 of the Tasaday. As a result of the discovery of these very primitive people, then president Marcos set aside 19000 acres of surrounding dense forest lands as a reserve. Access was restricted and all visitors had to be escorted by Elizalde.

After governance shifted under a new president, a Swiss team came to visit by themselves and discovered the Tasaday living in huts wearing t-shirts and blue jeans. They had apparently come from two other local tribes that had been connected to modern amenities for years, which they continued to trade with for cultivated food and more modern tools. They had been asked by Elizalde and other officials to remove their clothing and given fake stone tools to make them look more primitive. In addition, their language was really a dialect of Cotabato Manobo, spoken by most surrounding people.

Elizalde fled the Phillipines with $35 million of nonprofit money raised for the Tasaday. He died in Costa Rica addicted to drugs and impoverished. At least on the part of Elizalde, there was a hoax perpetrated.

On a more philosophical level, the Tasaday raised many questions about anthropological methods. Here’s the two big ones:

– How does one account for the masking effects of a tyrannical government and restricted access? In this case, that is what allowed Elizalde to dupe the scientists.

– What happens when a tribe asks for technology or an easy cure is available for a disease they’re suffering from? Does the anthropologist’s ethic lie in decreasing suffering or leaving their study culture as unperturbed as possible?

~Bluegrass Blue Crab

sources: 1987 NY Times article from right after hoax discovery, Time article from 1971 contact, and a follow-up 2002 BBC report, OSU website that admits both sides could be true

“Does the anthropologist’s ethic lie in decreasing suffering or leaving their study culture as unperturbed as possible?”

Great question, Amy.

When I studied abroad in Australia, we visited an Aborigine cultural center. A friend of mine was horrified to learn that most modern Aboriginals by their food at the grocery store and visit hospitals when they are sick- she always thought of them as living off the land and practicing traditional medicine. When she voiced this concern to our guide, he was shocked and asked her if she really wanted children to die of curable diseases so that her view of traditional cultures could be maintained. It was a very eye-opening discussion.

You’ve touched on the larger debate about the narrative of traditional systems: the romanticized idea of traditional livelihoods. Not only does that idea often leave out the challenges associated with such a lifestyle, but it ignores the many traditional societies that did not lead such a virtuous life (in terms of environment, peace, or otherwise).

Wait, you mean native cultures aren’t all exactly like Avatar and Dances with Wolves?

I would strongly recommend reading “Invented Eden” by Robin Hemsley. The Tasaday were not a hoax, although they were certainly misrepresented – they were never as isolated as they were said to be, for instance. The Tasaday’s own story of taking to the hills to avoid a small pox epidemic actually stands up very well – and is supported by independent evidence from the Spanish era that would not have been easily available at the time.

By the way, Elizalde died in the Philippines in May 1997 of cancer and was far from impoverished. Where did the nonsense about dying in Costa Rica come from?

Thanks for the book suggestion! It was actually really hard to find comprehensive sources, not just newspaper clippings from the episode.

I never fully said this, but the Tasaday community exists. It’s just the representation to the outside world that was a hoax – they weren’t their own tribe disconnected from everyone, just a remote community like many others around the world.

By the way, where did your info on Elizalde come from? Mine was from the BBC, which I consider a reputable source, but there are certainly lots of versions of this story flying around.

A friend of mine, a pleasant lady called Amy Rara nursed Elizalde in the last few weeks of his life.

Hemsley’s book is a must read. Hemsley had no particular commitment to any view of the Tasaday.

The Tasaday oral history says that they were in isolation for six generations. At 20-25 years for a generation that would place it in the late 19th century. Linguistic analysts who listened to recordings the Tasaday talking estimated that they can separated form Cotabato Manobo dialect for something over 100 years, placing the separation at around the same time as the Tasaday themselves said.

The clincher for me was a note in Ken De Bevoise’s Agent of Apocalypse, about historical epidemics in the Philippines, which I was reading in relation to other research I was doing. There was a serious smallpox epidemic in Cotabato in 1871, the only one, spread there by a boat from Zamboanga and recorded by the local Spanish medical officer.

I’ve since discovered that there is further evidence pinpointing the year of separation connected with disease but has not yet been published.

i will research related topic about them..