The following is the transcript of a talk I gave at DC Nerd Nite on September 16, 2023. Enjoy!

I need to begin with a disclaimer: It is impossible to talk about Project Azorian and the Glomar Explorer without sounding like you’ve gone deep into Dale Gribble territory. Azorian has everything a conspiracy theorist could ever want: Cold War espionage, a government coverup, a shady partnership with a celebrity entrepreneur, military contractors with their own plots for profiteering, and, in the middle of it all, there is a very big boat.

You’re going to get some cameos from Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon, as well as the guy who stole J. Edgar Hoover’s underwear.

Azorian was the OG Vast Government Conspiracy.

Even if you’ve never heard of the Glomar Explorer, these story beats are going to feel very familiar to you. There’s a good reason for that. Project Azorian was, and likely still is, the largest and most expensive covert operation in US history, but in its declassification, it also became the model for a generation of paranoid storytellers, from the X-files to Alex Jones.

Because of that, we can learn a little bit about how conspiracy theories work by looking at the foundation upon which many of them were built.

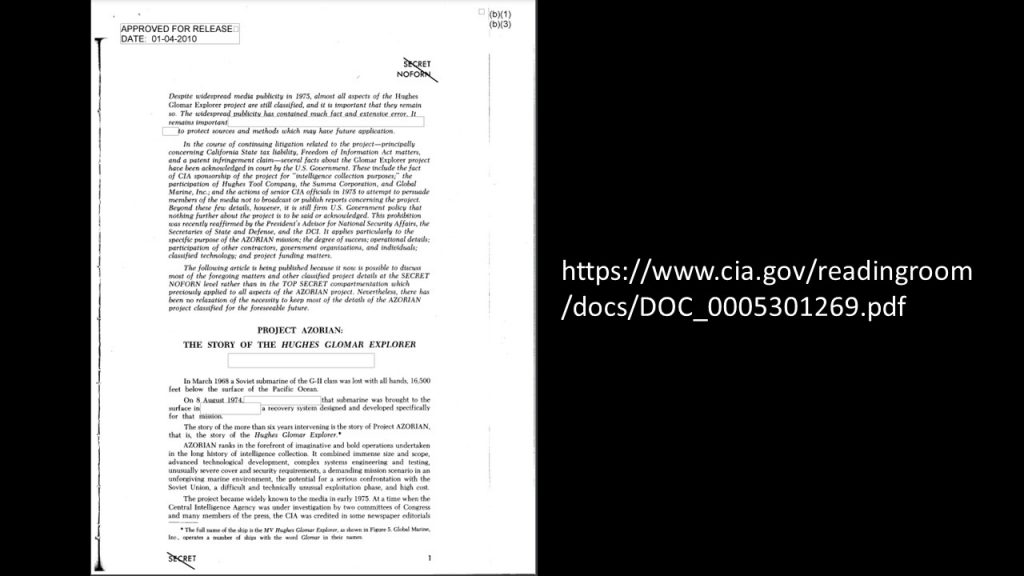

I have a link for you: https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0005301269.pdf

It’s the declassified report from the CIA describing the broad strokes of the operation (you can also find it by just searching for project azorian pdf). It is heavily redacted, but this was cleared for release in 2010 and you are allowed to read it and share it and store this document in your bathroom until your valet accidentally drains your pool into it.

It is entirely possible that there are parts of this mission that remain completely classified, and that some of the narrative has been changed to hide other objectives, so the only assurance I can give you tonight is that everything about this story that is true, is true.

It starts with a submarine. In April 1968, the Soviet K-129 sunk 1600 miles northwest of Hawaii, in water almost a mile deep. The US Navy detected the implosion on the same hydrophone array the Roger Payne used to record his album Songs of the Humpback Whale and managed to triangulate its location to within 5 miles of the wreck. The Soviets were looking for it, but they were looking in entirely the wrong spot.

The Navy then sent a specialized reconnaissance submarine called the Halibut to locate and photograph the wreckage.

We wanted this sub. K-129 carried an array of extremely valuable Soviet documents as well as three nuclear-tipped torpedoes. In the late 60s, no one thought a wreck could be raised from that depth. As far as the Soviets were concerned, those intelligence materials were safely out of reach.

Recovering the submarine, in secret, would give the US a huge intelligence advantage over the Soviet Union.

It took several years to turn ideas into action, but in 1970, then National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger proposed a wild and implausibly complex plan to President Nixon.

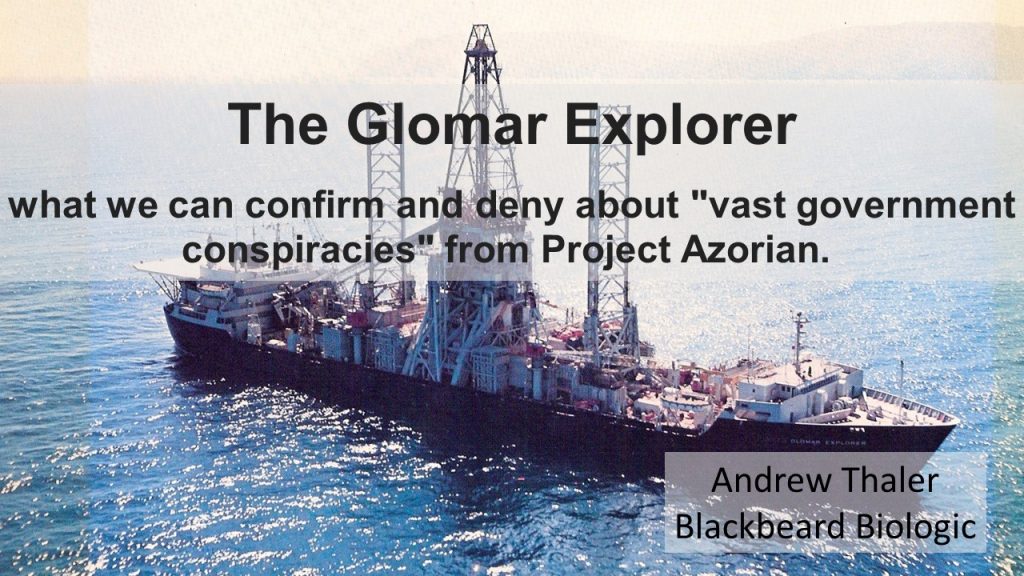

This was the plan: They would build a boat. Not just any boat, but a boat large enough that an entire Soviet nuclear submarine could be hidden inside its hull. And to facilitate the getting of that submarine, the boat would have a massive moon pool.

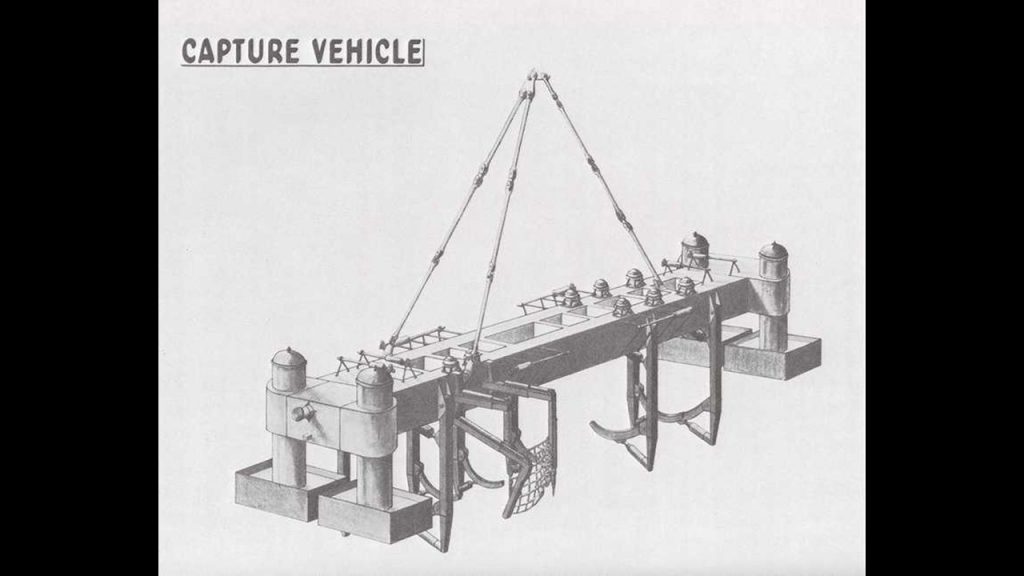

A moon pool, incidentally, is what we, in the oceangoing community generally refer to as A Hole. From that hole a capture vehicle would be lowered via almost a mile of cables to the seafloor, collect an entire wrecked submarine, and raise it into the hull, all without any outside indication that they were doing it.

Henry Kissinger wanted to build the world’s biggest claw machine.

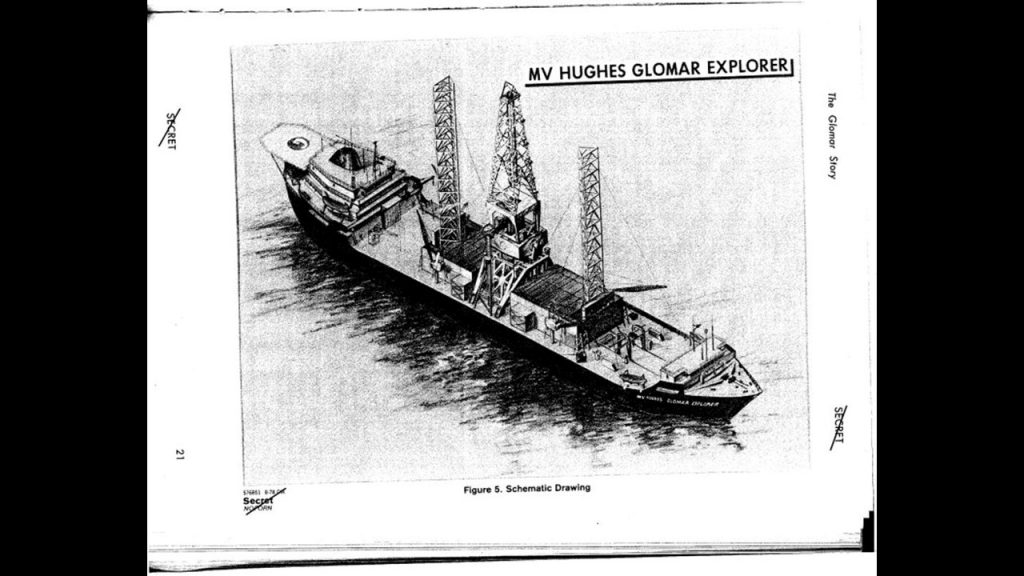

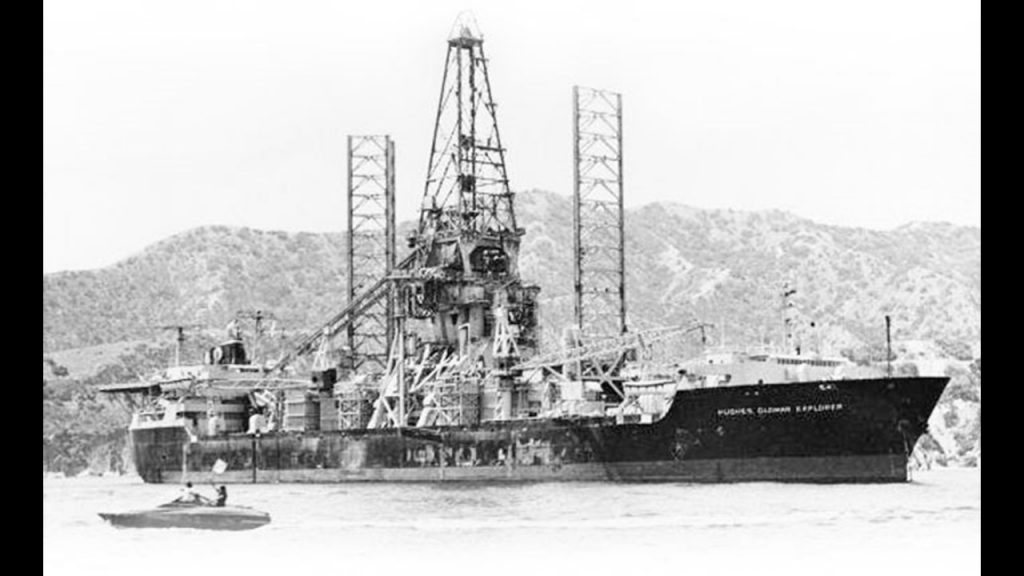

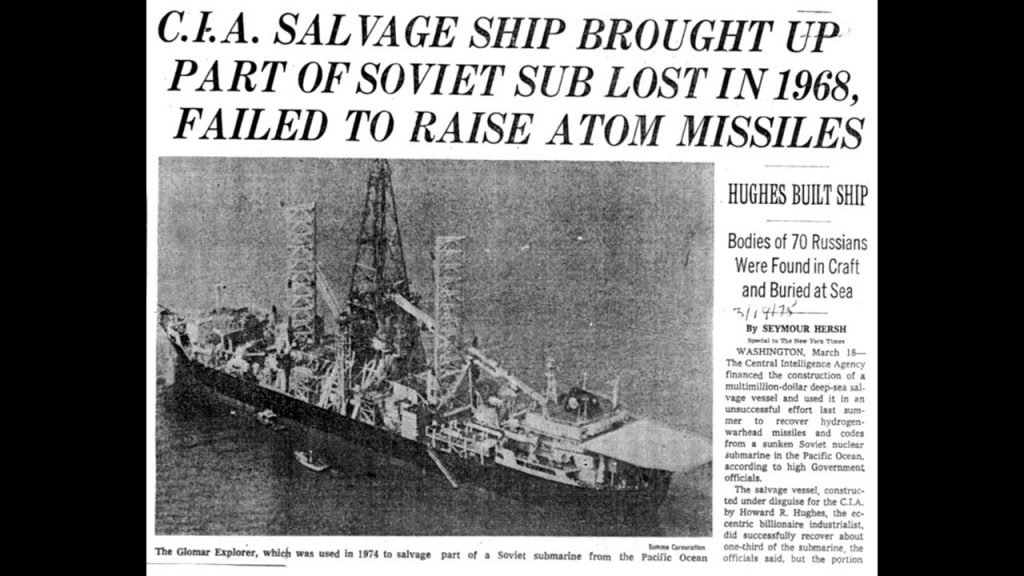

This is the boat they built. On the outside it looks like a drill ship. A little lumpier around the middle than a conventional drill ship, but it is still relatively unassuming. The massive hull hides its secret. Inside is the crane and gantry system that allows it to lower its capture vehicle to the bottom of the ocean and raise a shipwreck from the abyss. Work on the ship, dubbed the Glomar Explorer, began in 1972, four years after the submarine went down.

It should go without saying that this is not a great design for a boat. Generally speaking we like to avoid having a massive hole in the hull. In a traditional drill ship, the moon pool is tiny, barely bigger than the drill and certainly not sized for a nuclear submarine. When all the cable handling equipment is hidden away inside the boat, there’s a lot less room for things like, well, rooms. So the boat was big. And the boat was awkward. And the boat was very uncomfortable. But maybe, just maybe, it might do the job.

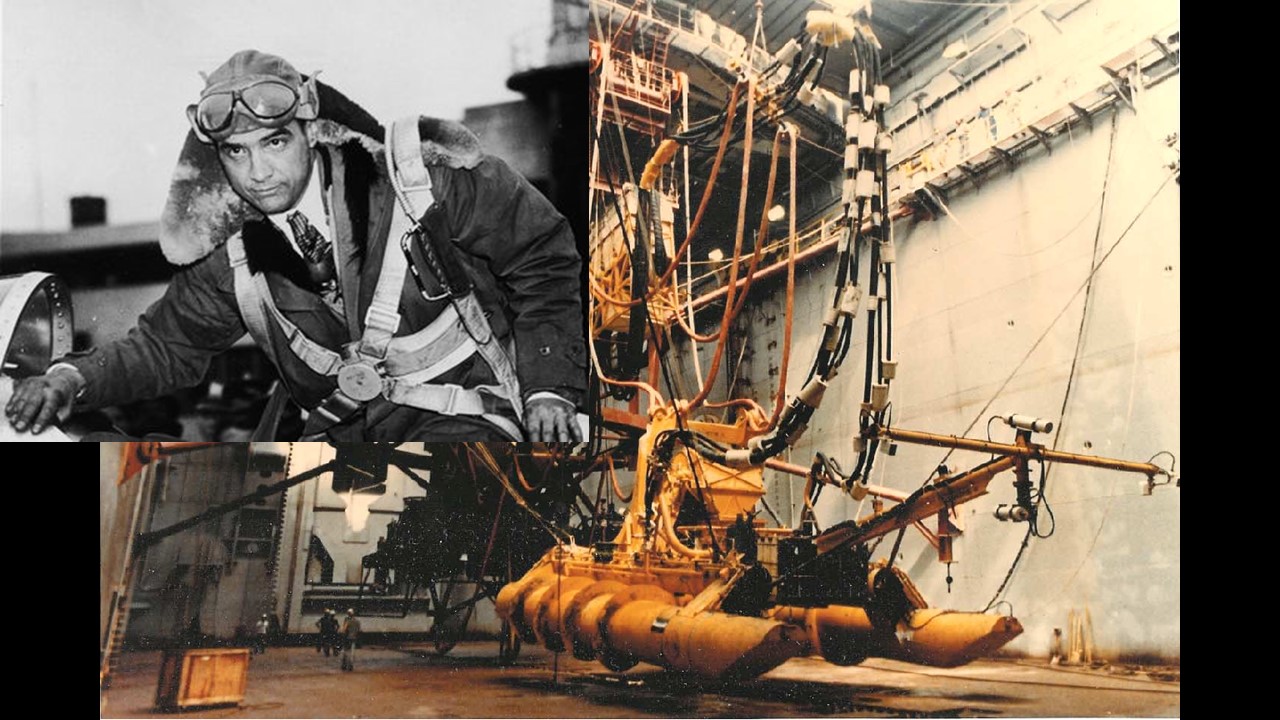

And to help make sure that job got done, the CIA needed someone with a vast resume of technical credibility, a businessman with broad international appeal, and most importantly, they needed a filthy rich weirdo who could credibly do a whole mess of ocean nonsense, without arousing suspicion.

And that brings us, at last, to Howard Hughes.

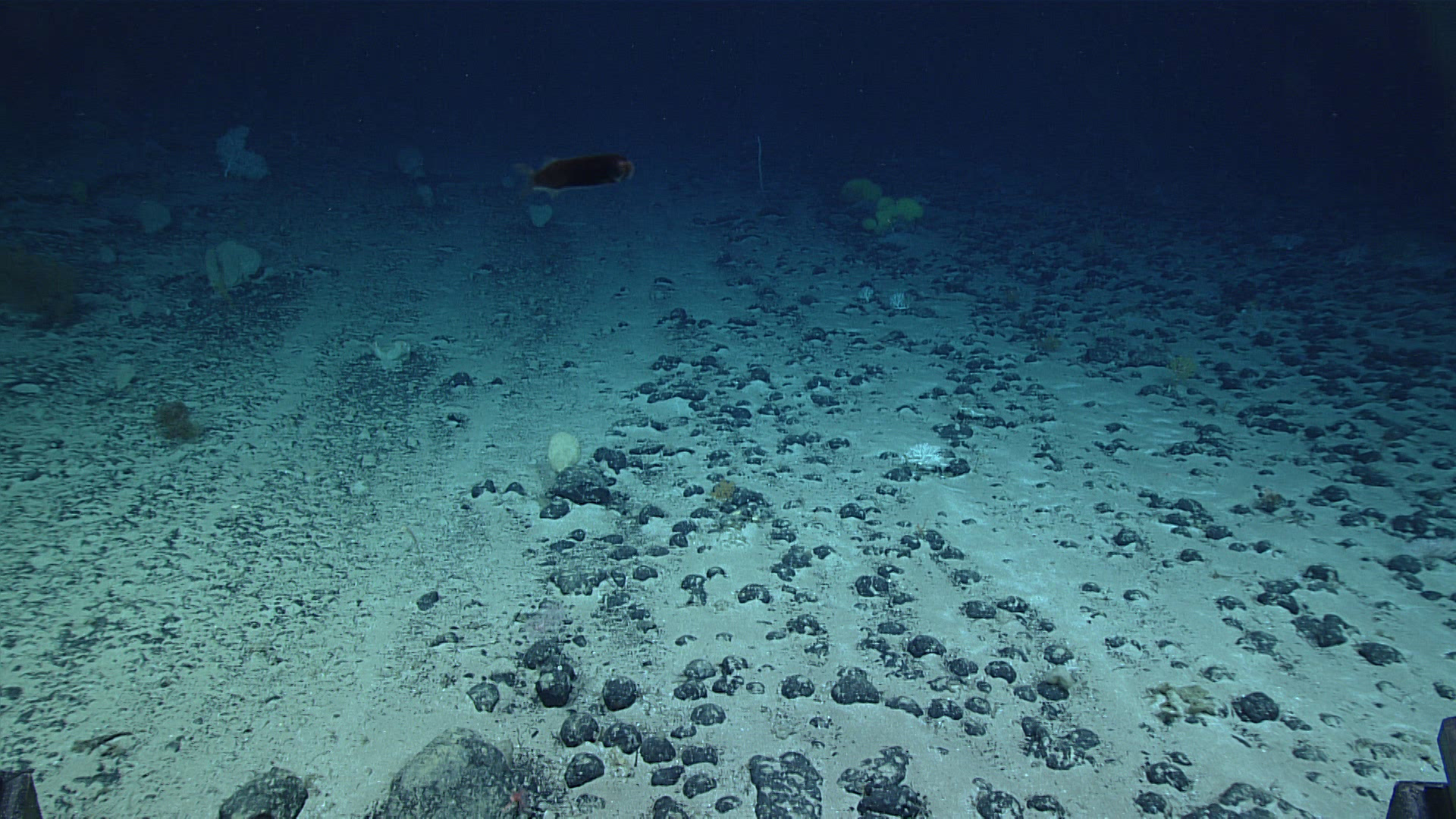

Howard Hughes, fascinated by the potential mineral wealth at the bottom of the ocean in the form of polymetallic nodules, would commission Lockheed to build the Glomar Explorer, the world’s first deep-sea mining vessel. From this ship, they would scrape the seafloor, bringing up ore samples from the abyssal plain. Deep-sea Mining was the cover story.

The ore is real. These nodules are rich in manganese, but also cobalt, nickel, and copper. And they look like this (hold up nodule). This is one of the nodules collected by the Glomar Explorer, as part of a later expedition.

To help sell this cover story, the CIA funded research into the financial viability of deep-sea-mining, hosted, through proxies, workshops and scientific meetings about the industry, some of which included Soviet scientists, and drummed up media attention about the wealth of mineral resources at the bottom of the ocean. This all happened while the world was in the midst of negotiating the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, and deep-sea mining, despite being an industry that did not actually exist, took center stage in these negotiations.

As the Glomar Explorer was being built, they also sent research ships into the general area of the wreck, to reinforce the lie and probe the Soviets’ reaction to ships in the area.

The deep-sea mining industry exists in its current form largely because of the groundwork laid by Project Azorian. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The actual mission is, oddly enough, one of the least interesting parts of this entire adventure. When the Glomar Explorer left US waters, it almost immediately picked up a tail from a Russia warship, who followed them at a distance throughout the operation. When they got onsite on July 4th, 1974, they spent almost a month trying to connect to the wreck, Soviet ships watching them the whole time. Finally, they locked onto the sub and began raising it to the surface, but partway up, two thirds of the wreck broke free and returned to the bottom.

For more on Project Azorian, check out Neither Confirm nor Deny: How the Glomar Mission Shielded the CIA from Transparency along with a recently released documentary under the same name.

We almost certainly don’t know everything they recovered, but what we do know is that two nuclear torpedoes, several code books, and the bodies of six sailors, along with the ships bell, were brought up from the seafloor. The CIA had their own documentary crew recording the entire operation, but that footage remains classified, with one notable exception: The crew held a burial at sea for the six Soviet sailors, and footage of that ceremony was later presented, along with the ship’s bell, to the Soviet government.

Now, the boat leaked because it had a giant hole in the middle of it, but the entire operation also leaked, and it leaked almost immediately. New York Times reporter Seymour Hersch was ready with a story while the operation was still underway, but the CIA managed to convince his editors to hold off on publication in order to avoid an international incident.

Investigative reporter Jack Anderson, who famously once had his staff dig through J Edgar Hoover’s literal trash and who Richard Nixon honest-to-cod tried to assassinate for unrelated reasons, then broke the whole story less than a month later, forcing the New York Times to rush out their own story with an explanation of why they chose not to publish. But it was already out there. Local papers had been speculating on the real reason for the Glomar Explorer’s construction since the very beginning.

When asked why he didn’t feel the need to hold back the story, Anderson replied “Navy experts have told us that the sunken sub contains no real secrets and that the project, therefore, is a waste of the taxpayers’ money.” And the CIA itself concluded that the Soviet Union took no action after the story was revealed.

The general consensus from Project Azorian was that the mission was an impressive technical achievement but also a complete intelligence failure.

Project Azorian cost the equivalent of $4.7 billion today. In comparison, the direct costs for Apollo 11 were a measly $3.0 billion, so collecting 1/3 of that submarine cost more than a moon landing.

Something really wild happened in the aftermath of Project Azorian: deep-sea mining became a viable industry, at least on paper. Lockheed continued to operate the Glomar Explorer, testing equipment and recovering polymetallic nodules from the middle of the Pacific throughout the 70s and 80s. Because so much of the initial cost of jumpstarting an industry was essentially fronted by the defense department, those early entrepreneurs had an enormous advantage. In some analyses, without Azorian, there would never have been enough interest and initial financing for the industry to get off the ground. At least, not for many more decades.

And that’s where I come into this story because I’m a deep-sea ecologist that studies how deep-sea mining will affect ocean ecosystems. In the early 90s, the rules dictating who and how people would be allowed to mine the deep ocean beyond national borders was codified in an annex to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, a treaty, by the way, which the United States has never ratified. Lockheed remained active in deep-sea mining until just last year. The Glomar Explorer itself continued operating into the 21st century. It was only laid to rest just a few years ago.

Arguably, the biggest outcome from Project Azorian was the acceleration of the Deep-sea Mining Industry.

This isn’t a deep-sea mining talk, but I’m here and there’s a bar if you want to chat about the industry as it exists today.

There are a few key lessons we can learn about Vast Government Conspiracies from Project Azorian. The first of which is that, for the most part, conspiracy theorists aren’t really all that creative. So much of modern conspiracy theory relies on this template that it acts like signal flair for quackery. And while the government absolutely engages in clandestine activities, yesterday and today, government is just a big word for people, and people are really bad at keeping secrets. Azorian was almost certainly the most expensive and complex clandestine operation in US history, and not only did it leak pretty much immediately, but it’s almost certainly true that the Soviets knew what was up from the moment the hull was laid.

Penn Jillette once gave an interview about how he creates great magic tricks, and in it, he says “the secret must be ugly.” The way to keep your audience from figuring out how a magic trick works is to make the real explanation so boring that there’s no reward for figuring it out. There’s no great “aha” moment. Knowing the secret kills your joy, and so you keep searching for a more exciting explanation. Both magic and espionage are exercises in misdirection. Secrets stay secret not because they’re kept in iron clad vaults, but because no one gets excited by the ugly answer. The boring answer. Clandestine operations aren’t hiding world changing knowledge, they’re hiding incremental gains in technology and intelligence that provide small advantages over perceived threats.

Even with Project Azorian being too exciting to keep secret, there were pundits arguing that it couldn’t possibly just be a mission to recover one submarine, there had to be a more exciting explanation. But in almost all cases, the fantastical story is the cover, not the operation. The best kept secrets aren’t just ugly, they’re boring. Boring secrets don’t leak.

There is one final epilogue to this strange chapter in American Espionage. After the initial leak and follow-up stories about the CIA’s attempts to quash that story, investigative journalist Hank Phillippi Ryan submitted a Freedom of Information Act Request to the CIA for any information pertaining to the Agency’s attempts to keep Project Azorian a secret. The CIA responded with what is now, probably, the most famous line in all of spycraft, which is known as the Glomar Response:

“We can neither confirm nor deny the existence of the information requested.”

Southern Fried Science is free and ad-free. Southern Fried Science and the OpenCTD project are supported by funding from our Patreon Subscribers. If you value these resources, please consider contributing a few dollars to help keep the servers running and the coffee flowing. We have stickers.