The deep-sea mining world was thrown a curveball last week when, as the spring session of the International Seabed Authority came to a close, the Metals Company, one of several commercial ventures seeking permission to mine polymetallic nodules in the Clipperton-Clarion Zone, announced that they would seek permission to mine directly from the United States, rather than through the international organization created by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea tasked with overseeing the industry. The United States is the only major economy that is not signatory to UNCLOS, though it accepts UNCLOS as customary law, and has a series of laws related to the exploration and exploitation of the deep sea which predate the Law of the Sea. These include the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act, the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, and, for a variety of logistical reasons, Section 27 of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, otherwise known as the Jones Act.

This is entirely new policy territory for the United States, and how the Hard Minerals and Lands Acts practically function for deep-sea mining in a post-UNCLOS era is going to take a few more days to digest, but my immediate reaction to The Metals Company announcement is that they are going to have a serious Jones Act problem.

The Jones Act is a protectionist law that regulates maritime trade within the United States. It is primarily focused on Cabotage, the movement of goods, among US ports. The Jones Act does several things relevant to a deep-sea mining company that wants to work exclusively under the aegis of the United States regulatory regime. The act requires that vessels operating in the transport of good between US ports be built, owned, and operated by US citizens. Jones Act ships have to be built in US shipyards. Jones act ships have to have US owners. Jones Act ships have to be crewed by US sailors (with several exceptions). The Jones Act also establishes health and safety rights for seamen.

Though they have created a US-based subsidiary, The Metals Company is a Canadian company. They operate two vessels, the Hidden Gem, owned by Allseas, a Dutch offshore contractor; and the MV Coco, owned by Magellan, a deep-sea logistics company headquartered on the British Crown Dependency of Guernsey. Neither vessel, of course, is Jones Act compliant. This is a particular problem for the Hidden Gen, a custom-converted vessel designed exclusively to operate The Metals Company’s seafloor production tools.

The big question, of course, is: Does the Jones Act apply to a deep-sea mining vessel extracting mineral resources in the high seas, beyond the US exclusive economic zone? Under the current regulations, and thanks to precedent established by the offshore wind, oil, and gas industries, the answer is “Yes.”

All Ocean Law is Weird Ocean Law. That’s true in the international regime as much as it is true in the US federal regime. There are a series of determinations work against The Metals Company. The first is found within the Deep Seabed Hard Minerals Act (which I will be digging more into later). Under this act, companies which have a license to mine the high seas issued by the United States have to land those minerals in a US port for processing in a US facility. The Jones Act cares about two points: the location of the vessel when cargo is offloaded, and the location of the vessel where cargo is onloaded. If both of those points fall within the US aegis, the Jones Act applies. Which leads to a second question: Does the seabed count as a US point?

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, which dictates how seabed resources can be exploited within the US EEZ extending outward to the extended continental shelf, also extends the definition of US points to the seabed. “U.S. laws extend to the subsoil and seabed of the outer continental shelf (OCS) and all artificial islands, installations, and devices attached to the seabed or erected thereon for the purpose of exploring, developing, or producing resources, including mineral.” But, of course, things also get weird. Pristine seabed that may become a future production site are not “US Points” until the seabed has been modified. There is also a lot of exceptions and carve-outs for non-production operations. Exploration, sampling, scientific research, and environmental impact assessments don’t create “US Points”, but commercial production of ore to be transported to a US port most certainly does.

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act concerns itself with areas that fall within the United State’s extended territory. The Metals Company wants a license to mine the high seas, in the Clipperton-Clarion Zone, in the middle of the Pacific, well beyond the United States’ boundaries. And for that, we need to determine if that mining site would also count as a “US Point”.

A funny thing happened in the Gulf of Mexico.

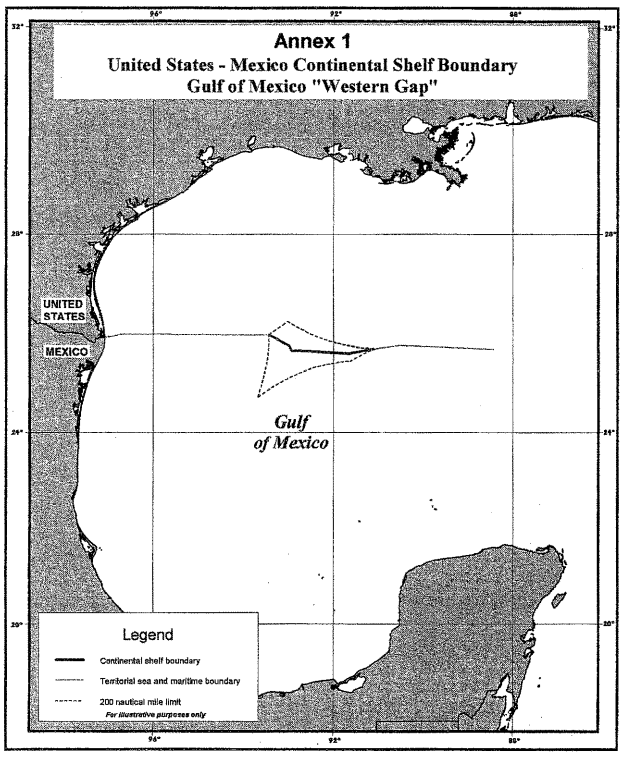

Within the Gulf of Mexico, there are two High Seas Pockets, regions that fall outside of any national jurisdiction but which are entirely surrounded by national borders. The Eastern Gap is bordered by Cuba, Mexico, and the United States. The Western Gap is bordered by only Mexico and the United States. These pocket seas should be high seas territories under international jurisdiction, but the convention within the UN is that bilateral treaties governing wholly contained High Seas Pockets take precedence. So in 2000, the US and Mexico made a deal. The United States claimed the seabed resources of the northern half of the Gap, Mexico claimed the seabed resources of the southern half of the Gap. In asserting that claim, the US also established jurisdiction over a portion of the high seas, for which US laws, including the Jones Act, apply.

So here we are now: The Jones Act says that vessels delivering cargo from “US Point” to “US Point” must be Jones Act compliant. The Deep Seabed Mineral Resources Act says that deep-sea miners operating under US licenses must deliver their ore to a US port for processing in a US facility. The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act says that production sites on the seabed count as a “US Point”. And the Western Gap Boundary Treaty extends those definitions to include “US Points” that would otherwise be considered areas beyond national jurisdiction. If the US claims it has jurisdiction over a high seas resource, the Jones Act applies to vessel operators working that resource.

The Metals Company has a Jones Act problem.

There’s a lot that is still up in the air right now. All we know for sure is that The Metals Company has put out a press release about working with the Trump Administration coupled with a leak from anonymous sources that there is a draft executive order floating around. There could be an EO released as soon as today or it could never come. Repealing the Jones Act has long been a goal of certain factions within the GOP, but that requires congress. NOAA both lacks the staff necessary to review a Deep Seabed Mineral Resources Act application and is under both a hiring and contracting freeze. All of which is happening under an administration that has a casual relationship with the rule of law.

When the Metals Company started discussion on building nodule refining capacity in the US, I perhaps surprised some of my colleagues by being generally supportive. If nodules have to be processed somewhere, the US is a smart location. Its unique relationship to the Law of the Sea gives it access to privileged markets, without which I don’t think the raw economics of deep-sea mining makes sense. Without the ability to separate deep-sea mining derived metals from terrestrial stock, there’s no mechanism to shut down terrestrial mining and the most compelling environmental argument for deep-sea mining disappears. But that depends on support from both the ISA and the United States, coupled with robust and transparent enforcement of a Mining Code.

This is a risky move by the Metals Company. Burning their existing relationship with the ISA for an All-American business pivot is incredibly precarious. Deep-sea mining is a multi-decade venture and depending on a single US administration for support is a huge gamble. It could pay off, but I don’t think it’s the gamble you make if you’re coming from a position of strength.

Southern Fried Science is free and ad-free. Southern Fried Science and the OpenCTD project are supported by funding from our Patreon Subscribers. If you value these resources, please consider contributing a few dollars to help keep the servers running and the coffee flowing. We have stickers.