As in-person negotiations on the future of exploitation in the deep ocean resume this week in Kingston Jamaica, we reflect back on the last two years of development as reported on our sister site, the Deep-sea Mining Observer. This article first appeared on June 30, 2021.

The spring and summer of 2021 will likely stand as the pivotal moment in the history of deep-sea mining. Months of intense protest amidst significant at-sea progress on environmental impact studies and prototype testing were capped off earlier this week by the explosive announcement that the Republic of Nauru, sponsoring state of Nauru Ocean Resources Inc, a wholly-owned subsidiary of The Metals Company (formerly DeepGreen), was invoking Article 15 triggering the 2-year countdown to complete the Mining Code.

An apparent sea change in the relationship between mining contractors, environmental NGOs, and other stakeholders, began in late March, when the Worldwide Fund for Nature announced a new campaign to get major corporations to pledge to exclude minerals produced from the deep sea from their supply chains until the impacts to the ocean were more thoroughly understood. These companies included BMW and Volvo, which have a major stake in electric vehicle manufacturing, and Samsung SDI, who produce small cell lithium batteries for electronic devices.

That announcement came just days before both GSR and The Metals Company were preparing for at-sea campaigns to continue their environmental baseline work and prototype nodule collector testing in the Clarion Clipperton Zone. The Metals Company’s Expedition 5B was one of several research cruises conducted over the last few years as part of a comprehensive plan to characterize the ecosystems, including pelagic communities, around their polymetallic nodule leases in the NORI-D contract areas and assess the potential impacts of their eventual nodule extraction operations. As DeepGreen, The Metals Company had previously lent the use of their ship, the Maersk Launcher, to the high seas plastic collection program The Ocean Cleanup.

Only days later, GSR launched its own four-week research campaign in collaboration with the EU MiningImpact program. During a month at sea, they tested the Patania II nodule collector prototype. The Patania II did suffer an engineering failure during sea trials which left the collector detached on the seafloor for several days before successful recovery to the surface, a scenario which is not unexpected during prototype testing. “This is pioneering engineering work and we were prepared for multiple eventualities.” said Kris Van Nijen, Managing Director of GSR in a press release. “…we were able to reconnect Patania II and we look forward to completing the mission, including further deployments of Patania II.”

With The Metals Company’s vessel, and two ships participating in GSRs programming, this may have been the largest simultaneous deployment of research vessels to the CCZ for the purposes of deep-sea mining research since the 1980s. But this time, they were joined by Greenpeace, who, in their first coordinated at-sea action against deep-sea mining, staged a protest against the Patania II trials, holding placards, painting “Risk!” on the side of the vessel, and sending a banner down to the seafloor. This action was complemented by matching land-based protests.

Back on shore, The Metals Company was also working to soften their image by collaborating with noted architectural design firm Bjarke Ingels Group to finalize the look of their integrated seafloor production system. The proposed collectors bear a domed shell, evoking the image of a giant isopod crawling across the seafloor, while the surface vessel deploys and retrieves the collector from a moon pool in its hull — not unlike the original design for the Hughes Glomar Explorer.

Protests on land and direct action at sea aren’t the only challenges that mining contractors are now facing. Greenpeace has launched a new front, targeting the permits for UK Seabed Resources, a subsidiary of US-based Lockheed Martin sponsored by the United Kingdom. In a letter directed to the British government, Greenpeace UK argued that the licenses were granted for an unlawful length of time, based on outdated legislation, violate the UK’s commitment to a precautionary approach to new exploitation, lack provisions for Environmental Impact Assessments, and outline an exploration area larger than UK Seabed Resources is authorized to operate within.

“What is most troubling about [Greenpeace UK’s] findings,” says Greenpeace representative and former EIC of the Deep-sea Mining Observer Arlo Hemphill, “is that a U.S. corporation has been using a foreign license to push a destructive new industry that the American people ultimately don’t want. By using foreign subsidiaries and potentially shady legal practices, Lockheed Martin is endangering our oceans and side-stepping the will of the American people for their gain.”

While press announcements draw attention to a variety of complaints that Greenpeace UK has lodged against UK Seabed Resources, the actual legal filing targets procedural issues regarding the timing of disclosure for key permitting documents and lack of compliance with existing UK laws regarding the issuance of mining permits. Notably, UK Seabed Resources currently only holds exploration permits to assess deep-sea mining prospects. They have not yet been issued any exploitation licenses from the International Seabed Authority.

In the wake of these protests, a collective of over 350 scientists and policy experts from 44 countries released a public letter urging a pause in the transition from exploration to exploitation while researchers work to characterize deep-sea ecosystems and better understand the potential impacts that deep-sea mining might bring. “We strongly recommend that the transition to the exploitation of mineral resources be paused until sufficient and robust scientific information has been obtained to make informed decisions as to whether deep-sea mining can be authorized without significant damage to the marine environment and, if so, under what conditions.“

And then, effective today, the Republic of Nauru invoked Annex I, Section 1(15) of the 1994 Agreement on the Implementation of Part XI of UNCLOS, colloquially known as Article 15, The Trigger, or the Two-Year countdown. In a letter addressed to the Council of the International Seabed Authority, the President of Nauru announced that they would be prepared to submit a plan of work in 2 years and thus requested the completion of the Mining Code be expedited pursuant to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

In a public statement, the Republic of Nauru provided additional details about its decision. “Nauru has proudly taken a leading role in developing the international legal framework governing seafloor nodules in the international seabed area (the Area). As the first developing country to sponsor an application for an exploration contract in the Area, Nauru helped realize the vision of the United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that this new industry be accessible and available to developing States. Given that Nauru Ocean Resources Inc (NORI), a Nauruan entity sponsored by Nauru, intends to apply for approval of a plan of work for exploitation, Nauru is following the appropriate procedure as detailed in the 1994 Agreement. The draft exploitation regulations for minerals of the Area have been under development for more than seven years and involved a series of transparent, inclusive discussions by the international community facilitated and led by ISA. Nauru considers that the process is nearly complete and stands ready to continue working diligently with ISA and all its Members and other stakeholders to finalize, negotiate and adopt a world class regulatory regime that allows for the responsible collection of seafloor nodules while ensuring the protection of the environment. At the same time, Nauru considers that there is urgency of concluding this work in order to provide the legal certainty required for this industry to move forward.”

Notably, Nauru indicated that the decision to invoke the Trigger was made by the government alone, and not at the urging of its mining contractor.

In a statement provided to the Deep-sea Mining Observer, GSR supplied additional context on the process of invoking Article 15. “It is important to understand that the adoption of regulations does not mean commercial activity can commence. Rather it provides a level playing field for contractors and will allow the submission of an application for mining under a set of pre-determined rules. These rules have involved extensive stakeholder consultation over the past seven years. Regulations will ensure that any future activity is subject to proper checks and balances, and they will also provide a rulebook for environmental impact assessments and monitoring. Having regulations in place does not mean an application will be approved.”

“The intransigence of the moratorium campaign has pushed Nauru and the contractors into a corner and a decision on the ‘trigger’ they would have preferred to avoid,” argues Dr. Saleem Ali, Professor of Energy and the Environment at the University of Delaware, who serves on the UN International Resource Panel and the science panel of the Global Environmental Facility, and has an advisory role with The Metals Company. “Engagement in a meaningful science-based consensus process on mitigation measures in good faith with the ISA by all stakeholders could have avoided this outcome.”

While some of the specifics regarding how the Trigger will be implemented are still to be determined by the Council, the process does not mean that mining will begin in two years. NORI and Nauru have declared that they intend to submit a plan of work within two years. This starts the countdown on finalizing the Mining Code itself. Should the Code remain incomplete at the two-year deadline, the plan of work will be evaluated on its own merits and any existing regulations that the Council has agreed upon.

“The press release on the ISA website suggests that NORI judges that within two years it may have reached a point where sufficient information has been gathered to apply for a plan of work. GSR is not in a position to comment on the environmental work that NORI has conducted or has planned, however, the current draft regulations foresee a one-year process (including public participation) to review applications, including an assessment of whether sufficient environmental information has been assembled. While the adoption of regulations does not rely on there being sufficient environmental information, the approval of a plan of work most certainly does.” adds GSR.

In response to the invocation of Article 15, the Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative, a registered Observer for the ISA, issued a letter of concern to the Council and Secretary General. “[It] is, at present, possible only to develop plans that will afford protection to these ecosystems using rules of thumb from the very different coastal ecosystems. Rushing the regulations to meet a two-year goal would run counter to the precautionary approach, which requires Member States to err on the side of caution. For example, the ISA has yet to agree on overarching Strategic Environmental Goals and Objectives, define ‘serious harm’ and associated adverse change, as well as specific criteria to operationalize, measure and monitor it, and put in place effective regional environmental management plans.”

“Additionally, we believe that triggering the two-year rule will not allow much of the relevant scientific research currently underway to be completed, communicated, and taken into account, preventing critical scientifically informed decision making. Two years is not a sufficient period for acquisition of the necessary scientific research to inform best environmental practices. The UN Decade for Ocean Science (2021-2031) offers a timely opportunity to gather the resources and expertise required to fill some of the deep-sea science gaps outlined above.”

In its statement, GSR also notes that there is a Sustainability Paradox at the heart of the deep-sea mining industry. “It may be important to recall why entities are looking to the deep ocean for metal in the first place. The climate and biodiversity crises are coinciding with a massive increase in global population. Decarbonising a rapidly urbanising planet will require huge amounts of primary metal. Obtaining metals from the planet, whether from land or the seafloor, will add to the carbon budget and impact biodiversity. This creates a paradox as the solution also contributes to the problem. All available approaches have impacts and effects. Global society needs to select solutions that have the least impact on the planet overall. Society needs to confront this reality so that the metals we all need can be

sourced in the most responsible way possible and for the benefit of all.”

“Society needs to confront this reality so that the metals we all need can be sourced in the most responsible way possible and for the benefit of all,” concludes GSR.

“UK Seabed Resources remains fully supportive of the ISA multi-stakeholder process that has resulted in a set of draft regulations, standards and guidelines which are intended to be both environmentally robust and economically viable,” says Chris Williams, managing director of UK Seabed Resources.

Dr. Lisa Levin, co-Lead of the Deep-Ocean Stewardship Initiative and Professor of Biological Oceanography at Scripps Institution of Oceanography argues that “Triggering this rule means that DOSI has an enormous amount of work to do, to bring deep-sea science to decision making and management of deep ocean ecosystems. That said, 2 years is a blink of an eye, especially relative to the time scales relevant for deep-ocean processes. Even at its most intensive pace, science cannot yield the information needed to manage this nascent industry in only 2 years. My hope is that the ISA will adhere to its World Ocean Day vow to increase global knowledge of deep-sea biodiversity for the benefit of humankind. This originates from its responsibility to ensure the effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects that may arise from such activities in the Area as well as to promote and encourage marine scientific research in the Area. Serious thinking is needed on how to achieve this mandate under the 2 year rule.”

We reached out to the International Seabed Authority and The Metals Company and will update if comments are provided.

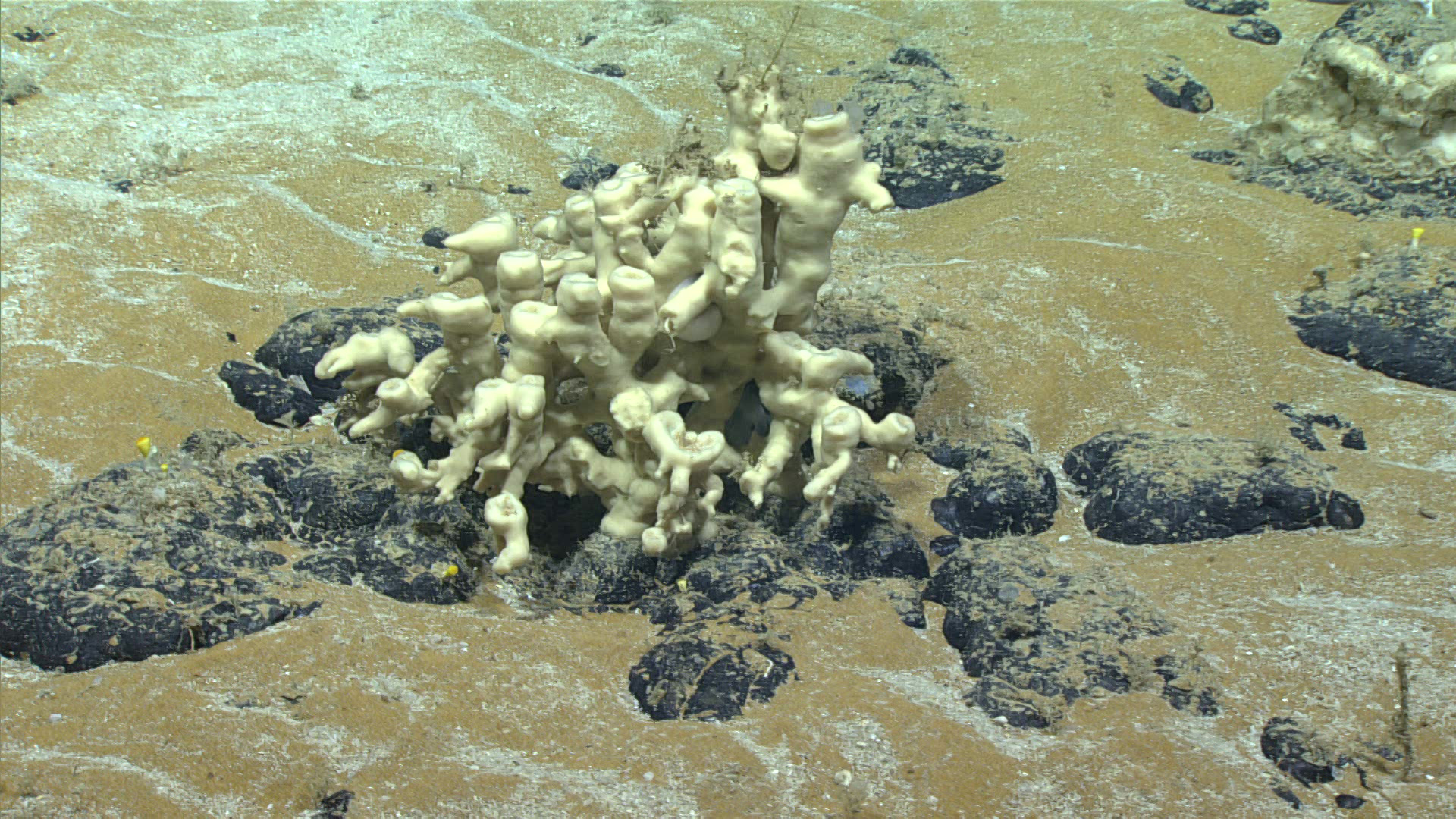

Featured Images: Sponges settled on a polymetallic nodule at a historic deep-sea mining test site off the coast of Florida. Photo courtesy NOAA.