On Friday, I posted about the financial model used to project the potential profits from a hypothetical polymetallic nodule mining model in the Clarion Clipperton Zone. This model, originally commissioned in 2018 and updated in 2021/22, had some puzzling prices for manganese in particular.

This model is extremely important. Beginning late this month, member states in the International Seabed Authority will continue negotiations on the mining code for the exploitation of deep-sea mineral resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Those resources fall under the Common Heritage principle, they belong to you, and they belong to me, and they belong to everyone. Revenue from the mining of these resources is supposed to be distributed to member states and the ISA in a just and equitable manner. How much those royalties will be, how and when they are distributed, how things like the an environmental mitigation and remediation fund are funded, are all currently being negotiated and that negotiation depends on having an accurate understanding of what the resources are actually worth.

In my blog post, I argued that, based on the 2018 model, the value of a deep-sea mine was off by about a billion dollars. I had the chance to chat with a few experts this weekend who helped clear up some those issues. The short answer is that the original model did not make sense when it was proposed in 2018 and does not work today. The value of manganese was extremely inflated based on 100% of recovery going to the electrolytic manganese market, a market that is much, much smaller that the manganese ore market.

Here’s the good news: an updated financial model was released at the last ISA session (warning, link downloads an excel spreadsheet).

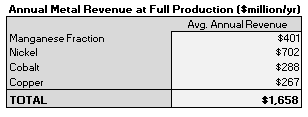

They’re no longer using the price for electrolytic manganese, but rather the fractional value of manganese in ore, at $475 per ton. The new model also feature a larger scale mining operation harvesting more nodules.

So where does that put the original 3-megaton nodule mining operation?

That looks a lot more believable. With the projections from 2023, the original 2018 mine is worth about $1.7 billion. Those projections are still pretty optimistic, with cobalt pinned at $60,000 per ton and nickel at $20,000 per ton. I don’t think we’ll see cobalt climb back up to $60,000 this decade. At current metals prices, we’re looking at a mining site worth about $1.3 billion per year.

The bad news, and the reason I started this whole dive into the financial model to begin with, is that I’m still hearing stakeholders cite the $2.4 billion value as gospel.

All together this means that that original conclusion, that the 2.4 billion dollar per year valuation doesn’t quite make sense, and I wasn’t off based to be confused by it. That $1.2 billion value for electrolytic manganese was the number running through the models when Nauru invoked the 2-year trigger in 2021. That value proposition was off by almost a billion dollars.

Fortunately, the constant refrain of the deep-sea mining negotiations is that “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed” and the financial regime for determining how revenue from deep-sea mining is distributed in accordance with the Common Heritage principle has yet to be finalized.