As a marine biologists just beginning my deep-sea education, conservation as a priority was an alien concept. The deep sea was the last true wilderness, distant and alien, impossibly difficult to access. We knew that exploitation was coming, companies had been exploring the potential of deep-sea mining for decades, but they always seemed to be generation away. Conservation was a question for my scientific descendants. For my peers and me, we still had a few good decades left in the golden age of exploration that began in the 1970’s with the first discovery of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. That age is about to end.

As a marine biologists just beginning my deep-sea education, conservation as a priority was an alien concept. The deep sea was the last true wilderness, distant and alien, impossibly difficult to access. We knew that exploitation was coming, companies had been exploring the potential of deep-sea mining for decades, but they always seemed to be generation away. Conservation was a question for my scientific descendants. For my peers and me, we still had a few good decades left in the golden age of exploration that began in the 1970’s with the first discovery of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. That age is about to end.

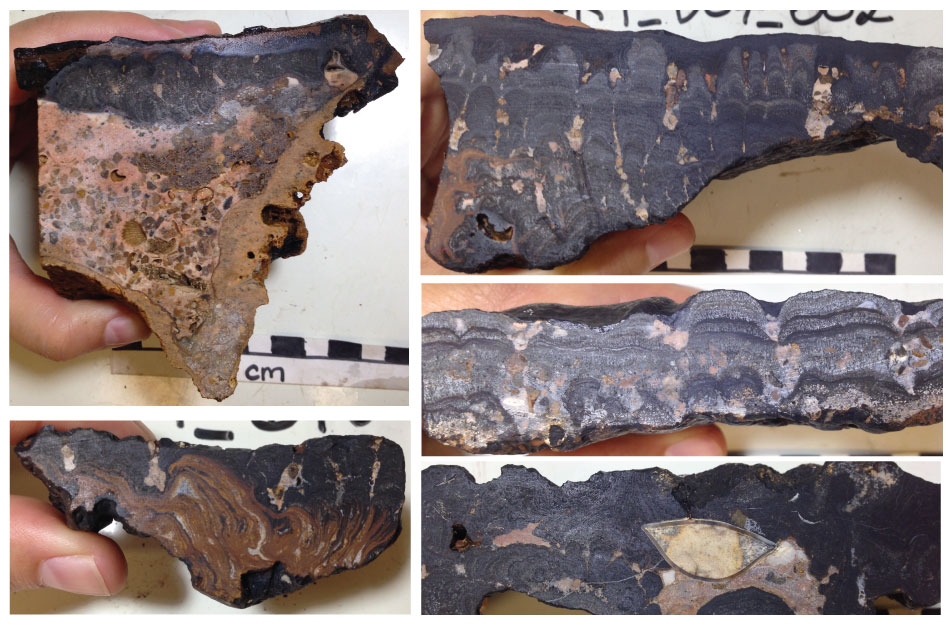

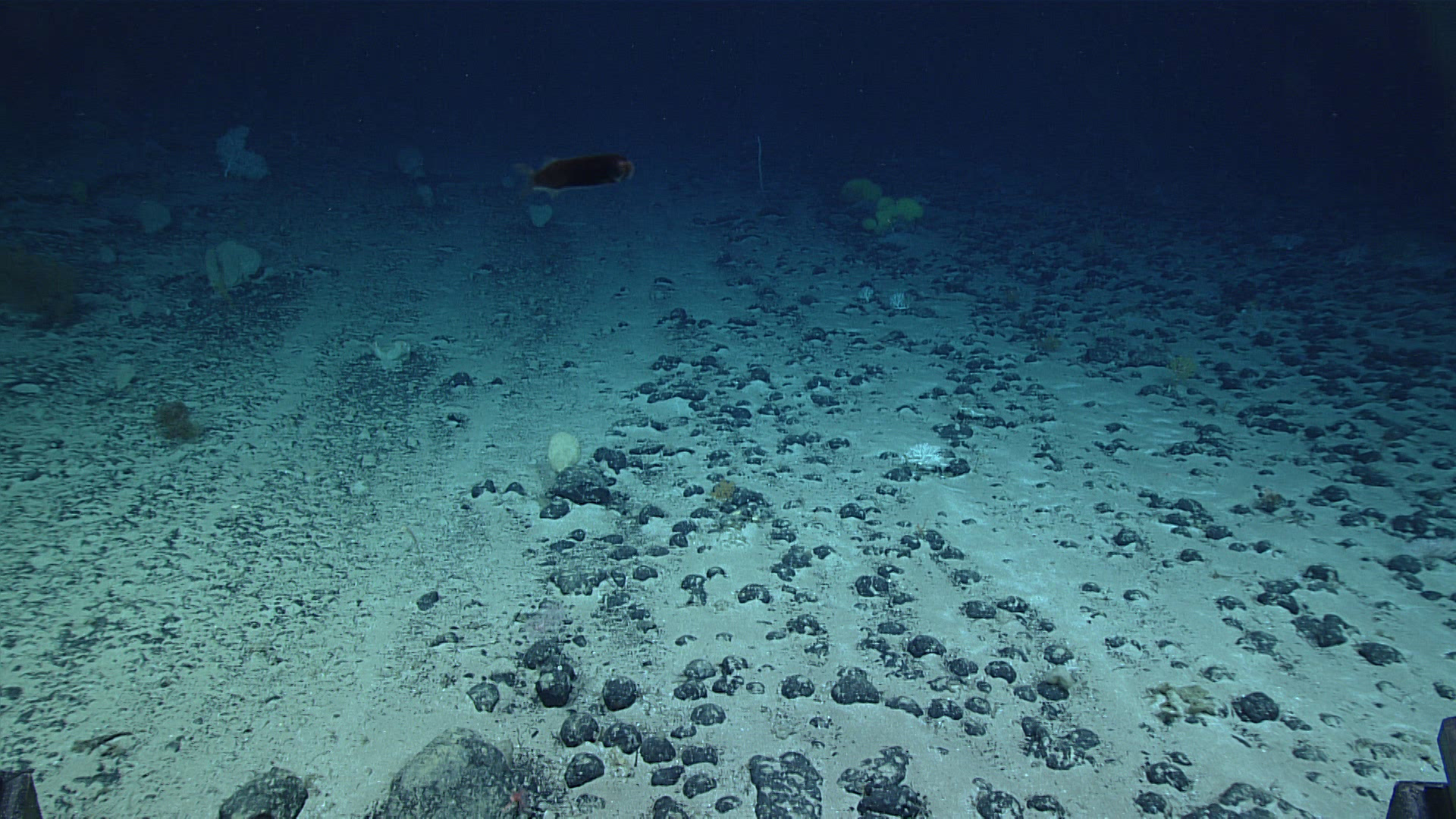

The reality of deep-sea exploitation is imminent. The first hydrothermal vent mining lease has been issued in the territorial waters of Papua New Guinea. The International Seabed Authority, which regulates seafloor extraction in international waters, has approved the first two mining exploration permits for seafloor massive sulfides in international waters. Manganese nodule extraction, once quashed by a global decline in metal prices, has recently reappeared. Crustal metal deposits are fast becoming a viable resource. The isolation of rare earth elements from the seafloor, a newcomer in deep-sea exploitation, could open up new, massive deposit for critical electronic components. All of these are likely to occur within the next few decades.

It is important, in these situations, to remember that industry is not, by default, the enemy. I would love nothing more than total protection from all exploitation for deep-sea hydrothermal vents, but that is an idealistic goal. We have a growing, upwardly mobile human population that demands resources. We recognize the inherent right of human beings to improve the quality of their lives, both individually and as a society. Development is not something that can be stopped, but it can be controlled, it can be regulated, and it can be done responsibly. While outright opposition to development may delay the inevitable, it will rarely halt it outright. As biologists and conservationists, we owe it to the systems we study to guide industry towards responsible practices, and minimize and mitigate the ecological insult from industrial exploitation.

Despite their apparent rarity, hydrothermal vents are present throughout the world ocean at volcanic hot spots and active spreading centers. Everywhere that we have predicted hydrothermal activity, we have found them. These are highly dynamic ecosystems, subject to frequent natural disturbance, and have evolved to be highly resilient to even catastrophic natural disturbance. How resilient they are to the added insult of anthropogenic disturbance remains to be seen.

Over the last week, ~40 scientists, conservationists, and industry and governance representatives gathered (some virtually) in Galway, Ireland to discuss the mining of deep-sea hydrothermal vents and establish methodological standards for baseline assessments of the geology, ecology, and connectivity of hydrothermal vent ecosystems, outline best-practices for establishing biological reserves and off-sets, and formalize the process of creating an Environmental Impact Assessment for hydrothermal vent mining. Representatives from the mining industry, the International Seabed Authority, geneticists, ecologists, and geologists or all stripes (including myself) participated in the first of what will hopefully be many VentBase working groups.

The importance of baselines

The central focus of the VentBase workshop was to establish best practices for conducting an environmental survey prior to exploitation. Baselines matter. With a robust environmental baseline we can assess the diversity and abundance of species within a vent system, identify critical habitats , determine the degree of connectivity among hydrothermal vents in a region, and locate areas of exceptional and representative biological diversity to be set aside for preservation. By standardizing methodology, we can ensure a minimum level of quality so that independent reviewers will be able to critically and confidently assess a company’s Environmental Impact Assessment. Standard methodology enables comparisons among multiple vent regions and contribute to our scientific understanding of hydrothermal vents.

These formalized recommendations will be submitted to the International Seabed Authority to be considered for incorporation into their requirements to receive an exploration permit for hydrothermal vent mining.

Critical to this baseline process is identifying preservation or reserve areas. The central question of the biological team boiled down to “what makes a good reserve?” Should a reserve be representative of the total biodiversity of the mining site? Should it be a well-connected upstream site that has the potential to recolonize a mined site? Should it be representative of the general biogeography of hydrothermal vents in the region? These questions are still being discussed, but without an accurate, rigorous, standard, environmental baseline, it would be impossible to identify a reserve that fulfills any of these goals.

While I cannot speak for the whole group, for me, personally, the big questions are: If a vent ecosystem is wiped out, will the community eventually recolonize from other sources and, if it doesn’t recolonize, will we have lost irreplaceable biodiversity in a particular biogeographic province?

Outcomes and future directions

The goal of the first VentBase meeting was to standardize environmental baseline assessments during the exploratory phase of deep-sea mining. These baselines will not only allow us to locate potential preservation sites, but to assess changes to the community after mining has completed. Our first set of recommendations, which will be presented to the International Seabed Authority in the upcoming weeks, do not address environmental monitoring during extraction, or long-term monitoring after mining has concluded. These are critical issued that must be addressed in the near future.

We are currently in an unprecedented situation where conservation considerations precede exploitation. Although deep-sea hydrothermal vents are among the most inaccessible ecosystems on the planet, few other ecosystems will have been as well-studied before industrial exploitation begins. Ecosystem changes from anthropogenic influences will be well-documented, conservation efforts will be informed by thorough ecologic studies.

Research at hydrothermal vents is expensive. Only a few nations have remotely operated vehicles capable of scientific sampling and even fewer have human occupied submersibles that can conduct this sort of research. Currently, the only institutions with the financial resources to support these rigorous baseline assessments are those that stand to benefit from deep-sea hydrothermal vent mining. It is only through partnerships with industry that we can conduct the kinds of baseline studies we need to assess the ecologic impacts of deep-sea mining. It is possible for industrial exploitation to proceed while retaining a conservation and stewardship ethic. Armed with detailed baseline information, scientists, conservationists, and industry can (slowly) move forward with environmentally responsible development.

Thank you for this interesting post. I heard about this event and being based in Galway, was going to gatecrash it to come and meet you! Perhaps next time.

Thanks Andrew, very valuable info – I didn’t know VentBase existed, so greatly appreciated and I thoroughly share your perspectives. Having being directed/diverted from deep sea fishing only a few months back from Mission Blue and other pages, I have been following this issue as best I can keep up considering the many species and Oceanic conservation concerns, yet upon exploring the InterRidge, Census of Marine Life and the affiliated pages, it certainly raised the eyebrows, especially then reading many of the PLoS ONE documents as well as the letter to I.S.A from InterRidge – that indeed raised some quite serious questions. Understandably, development progress is inevitable and unstoppable, but business, as on land, not only does not have brakes, the accelerator seems to be manipulated beyond any cruise control, driving the way with marketing – I thought Nautilus was a gentle passive creature from the depths of our Ocean as well as history!… I reckon this should be abated in the same marketing manner as visualised for Tobacco – Plain Packaging with warnings!

Interesting^^