Yesterday, we published a rundown of all the ways in which Trump’s Project 2025 would impact ocean science and conservation. Trump’s Project 2025 is an agenda, a glimpse at what a future administration might do. Trump already served one term as president. We already know what the Trump Ocean Doctrine looks like, and it doesn’t look good. In January 2021, when the dust had settled and President Biden had secured his presidency, we took a look at what four years of Trump leadership did to America’s oceans.

It’s worth reminding ourselves just how weird things got.

Donald Trump secures his legacy as the worst ocean president in American history.

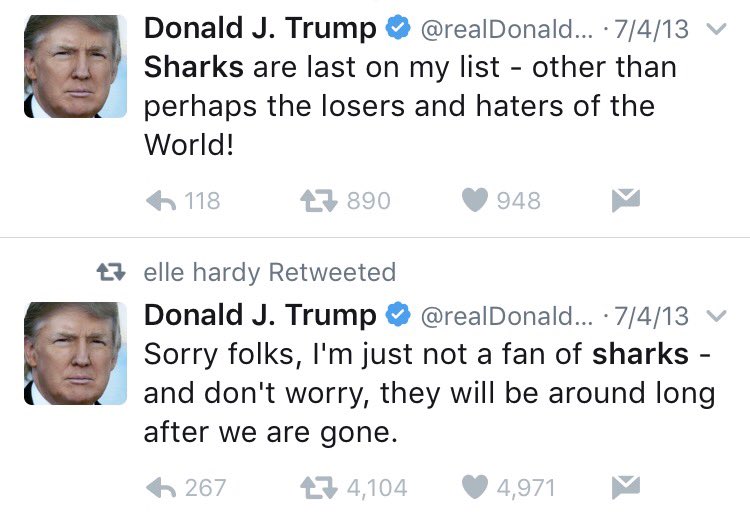

Donald F. Trump hates sharks. We learned that in 2013, when, during an entirely uncontroversial discussion about shark conservation foundations on Twitter, the would-be President of the United States of America blocked a small cohort of marine scientists.

Gracing David Shiffman and myself with a timeline blissfully free of his insufferable Tweets for eight years was the only good thing he has ever done for the ocean.

Initially, it appeared as though Trump’s war on the oceans would take a backseat to his other social, judicial, and environmental atrocities. Though a troubling selection for a host of reasons, Wilbur Ross’s appointment as Secretary of Commerce was seen as a relatively non-threatening move. His letter to NOAA staff, reassuring them that his department would continue to follow best-available science, was met with praise. His initial leadership appointments received bipartisan support.

It is clear now in hindsight, that that initial optimism was intensely naïve.

2017 started slow. The Trump Administration’s focus on dismantling the Department of the Interior left many insiders suspicious that leadership had simply not yet figured out that NOAA was in Commerce.

In April, the Administration unveiled an Executive Order for offshore energy which was severally lacking in a a plan for offshore wind but rather effectively returned the US to the Bush Era policy of Drill, Baby, Drill, opening vast swathes of the US coastline for offshore oil and gas exploration. Governors from both parties protested this move, which would harm tourism, fishing, and coastal environments. The order also opened up the High Artic for oil leasing.

June is usually declare National Ocean Month. In his first Ocean Month proclamation, the President raised alarms by declaring the ocean underutilized, echoing a commitment to exploitation rather than preservation.

Other moves would have huge ramifications on the oceans. The Trump Administration formally withdrew from the Paris Agreement, initiated a process to review all National Monuments for reclassification, launched their first budget war against NOAA (which would culminate in 2019), failed abysmally in its response to Hurricane Maria, and floated the idea of appointing AccuWeather CEO and serial sexual harasser Barry Myers as NOAA Administrator.

2018 is when the Trump Administration’s war on the Ocean really began to ramp up. President Obama’s National Ocean Policy, one of the most consequential pieces of ocean legislation since the Guano Islands Act, was rescinded and replaced with a milquetoast directive which erased climate change, environmental protection, and environmental justice from the directive. Trump’s ocean priorities were a litany of handouts, culminating with a mandate that “Federal regulations and management decisions do not prevent productive and sustainable use of ocean, coastal, and Great Lakes waters.”

“The policy reflects a shift from ‘use it without using it up’ to a very short-sighted and cavalier ‘use it aggressively and irresponsibly.'” said former NOAA Administrator Dr. Jane Lubchenco.

Trump’s new oceans policy washes away Obama’s emphasis on conservation and climate

Commerce Secretary Ross backtracked on his commitment to science-based policy, issuing directives to eliminate regulatory hurdles for offshore oil and gas exploitation. This included challenges to the Endangered Species Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, and the National Marine Sanctuaries Act. He also extended the Gulf of Mexico Red Snapper seasons against the advice of fisheries agencies. Later court cases would reveal that this was done knowing that it could causes massive overfishing. In addition, Ross overruled science-based fisheries quotas for summer flounder. According to the Center for American Progress, “It was the first time in the commission’s history that the secretary of commerce overruled its science-based policy determination.”

During the year, the Administration also issued more permits to allow seismic testing, causing significant harm to fragile marine mammal populations and continued to advance its plans to reduce marine national monuments.

That fall, Hurricane Florence, described by Trump as “tremendously big and tremendously wet”, ripped through the East Coast, dumping historic rainfall on North Carolina. While touring the wreckage, the President pointing to a derelict vessel pushed up on shore and told a man who had just lost almost everything “at least you got a nice boat out of the deal.”

There were few positives for American ocean policy in 2018. The Administration failed to hamstring the National Climate Assessment, which revealed that climate change would have major impacts on oceans and fisheries. The President also signed the Save Our Seas Act, giving NOAA the authority to declare severe marine debris events and coordinate ocean cleanup efforts.

This was also the year we learned far too much information about the President, his sex life, and his obsession with Discovery Channel’s Shark Week. Adult film star Stormy Daniels reported that Trump told her “I donate to all these charities and I would never donate to any charity that helps sharks. I hope all the sharks die.”

And that, my friends, is how it came to pass that half a decade later, the future President of the United States blocked me on Twitter.

2019 left ocean scientists, conservationists, and managers exhausted and appalled. It was the year that Commerce and the new acting NOAA Administrator, Neil Jacobs, unveiled a Budget to Decimate NOAA.

The Administration pushed rules to weaken the Endangered Species Act. Not only did Trump refused to recognize the threat of climate change to the Arctic, but his Secretary of State declared that melting sea ice would create the “21st century Suez and Panama Canals.” And the President continued his push for offshore oil and gas exploration.

This was also the year that the Trump Ocean Doctrine got weird. He started a fight with 16-year-old Greta Thunberg on Twitter (and lost, bigly). He seriously explored the potential for the US to buy Greenland, which launched a bizarre feud with the Danish Prime Minister (and which, for reasons which remain utterly inscrutable, the Washington Post decided to opine that the idea was “far from absurd”, despite it being patently absurd). And he announced that the US has formally met with the Prince of Whales (a strange claim since most whales are governed via a direct democracy, while orcas and pilot whales are anarcho-socialist collectivists).

There were victories in 2019, too. Trump’s plans to expand offshore drilling in the Artic and Atlantic were put on ice under judicial and legislative pressure. And after tremendous opposition from within and without, the nomination of serial sexual harasser Barry Myers, who had to pay settlement to 35 women after a federal investigation determined that his company subjected women to sexual harassment, collapsed. He would not serve at NOAA, leaving acting administrator Neil Jacobs in place, unaware of the oncoming storm.

And then came Sharpiegate. Sharpiegate was a clarifying moment within the civil service. It was a moment that transcended the superficial absurdity of circumstance. When history books are written about the Trump Era, Sharpiegate will mark a turning point. It wasn’t the first time the civil service fought back, but it was the largest rebuke of a sitting president by career civil servants in modern history.

We don’t need to revisit the specifics of Sharpiegate here. The event has been well documented. What hasn’t been as thoroughly touched upon is how deeply it affected the rank and file staff of the agencies under assault. They pushed back, with the public’s support. They made it clear that the politicization of NOAA’s weather forecasts could not be tolerated. They pelted acting administrator Neil Jacobs with vegetables when he attempted an appeasement tour of one of the weather centers. Allegedly.

There was fallout and, in the coming years, retaliation, but, for the moment, America had looked at the President’s behavior and said “hell no”.

2020 was a race to the finish line. Trump gutted the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument and he made a last ditch effort to push through more offshore oil and gas. He auctioned off US fisheries to the highest bidder and rolled back key fisheries management provisions. He appointed climate change deniers David Legates and Ryan Maue to key positions in NOAA.

And, on a positive note, he signed the Great American Outdoors Act, which provides funding for national park maintenance.

But new ocean policies were largely hamstrung by the singular dominant force of 2020 — the COVID-19 Pandemic. Even COVID relief wasn’t safe from Trump’s ocean rage. Though the CARES provides $300 million to support US fisherfolk, insiders report that they faced pressure from political appointees to remove that line item.

It isn’t just the big policy moves that solidify Trump’s legacy as the worst president for the oceans in American history. Within the bureaucracy, Trump appointees have gummed up the works in ways that will continue to stymie ocean research for years. Loyalists within the Office of Management and Budget, which oversees, among other things, agency compliance with the Administration’s policies, have mounted an unprecedented campaign against NOAA projects, grinding research to a halt for numerous projects which were already funded and are now years behind schedule.

The drumbeat of continuing resolutions, rather than actual budgets, prevented many Federal employees from performing their duties. It turns out that not being able to plan more than a few months in advance makes it hard to organize a major research campaign. The Executive Order that revises certain federal employees’ employment status has many civil servants worried about their future careers.

And it’s not just what the Administration did, but what it didn’t do that hurts. The lack of any major federal initiative to advance aquaculture has slowed the growth of the entire industry.

But here’s the good news: Very few of the Trump Administration’s actions have staying powers and President Biden can quickly sweep away most of the executive orders and roll back broken regulations. The real tragedy is the attrition of the federal civil service, the loss of expertise, and the loss of four critical years to turn the tide.

What we’ve lost, more than anything else, is time.

With impeachment looming following a failed coup, it’s unlikely that the last days of President Donald Trump will see any new policy. And yet, one of his last acts as president was to veto a bipartisan bill that would ban the use of gillnets in Federal waters off the coast of California. Having lost the House, the Senate, and the Presidency, been impeached twice, and facing demands for a swift removal before inauguration, President Donald Trump could not help but fire a parting shot at the ocean.

Southern Fried Science is free and ad-free. We use Amazon Affiliate links when we discuss consumer products, which provides us with a small kickback if you purchase through those links. If you enjoy Southern Fried Science, consider contributing to Andrew Thaler’s Patreon campaign to help keep the servers humming as well as supporting the development of open-source oceanographic equipment.