President, Shark Advocates International

Sonja Fordham founded Shark Advocates International as a project of The Ocean Foundation in 2010 based on her two decades of shark conservation experience at Ocean Conservancy. She is Deputy Chair of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group and Conservation Committee Chair for the American Elasmobranch Society, has co-authored numerous publications on shark fisheries management, and serves on most of the U.S. federal and state government advisory panels relevant to sharks and rays. Her awards include the U.S. Department of Commerce Environmental Hero Award, the Peter Benchley Shark Conservation Award, and the IUCN Harry Messel Award for Conservation Leadership.

A new study confirming the mysterious deepsea Greenland Shark as the world’s longest lived vertebrate has made huge news in the last few days – from Science News and BBC to People magazine and the Wall Street Journal. While some scientists are questioning whether these sharks live quite as long as estimated (392 years ± 120), most agree they could well live for a century or two and – as a result — are particularly vulnerable to overfishing. Experts also warn that risks to Greenland sharks may be increasing as melting sea ice changes Arctic ecosystems and makes fishing in the region more feasible. Study authors are among those urging a precautionary approach to the species’ conservation. In other words, an incomplete picture of status and threats should not be used as an excuse for inaction. So what might be threatening Greenland sharks today, and which upcoming policy opportunities might warrant consideration, given worldwide interest in these jaw-dropping findings? To come up with some ideas, I first took a look back.

A new study confirming the mysterious deepsea Greenland Shark as the world’s longest lived vertebrate has made huge news in the last few days – from Science News and BBC to People magazine and the Wall Street Journal. While some scientists are questioning whether these sharks live quite as long as estimated (392 years ± 120), most agree they could well live for a century or two and – as a result — are particularly vulnerable to overfishing. Experts also warn that risks to Greenland sharks may be increasing as melting sea ice changes Arctic ecosystems and makes fishing in the region more feasible. Study authors are among those urging a precautionary approach to the species’ conservation. In other words, an incomplete picture of status and threats should not be used as an excuse for inaction. So what might be threatening Greenland sharks today, and which upcoming policy opportunities might warrant consideration, given worldwide interest in these jaw-dropping findings? To come up with some ideas, I first took a look back.

BACKGROUND

According to ICES, Greenland sharks are found from the Arctic Ocean to the temperate North Atlantic, off Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, and Ireland, with occasional records further south (including the US Gulf of Mexico). Scientists speculate that Greenland sharks venture even farther, but stay down deep where the temperature is to their liking (below 5°C/41°F) and are therefore rarely encountered. Greenland sharks are found from inshore zones to continental slopes and depths down to ~1,800 meters, nearing the surface only in areas with very cold water.

There are no scientific estimates of Greenland shark abundance (using traditional stock assessment methods). The IUCN Shark Specialist Group (SSG) classifies this sizeable dogfish as Near Threatened, according to Red List criteria.

History of fishing (based on ICES & SSG summaries)

Greenland sharks have been fished by Scandinavian, Icelandic, and Inuit cultures for centuries, as far back as the 1200s in Norway. While meat, leather, and teeth have been used, the species was historically targeted for liver oil, particularly from the late 1800s to mid 1900s. Icelandic fisheries, usually retaining only the liver, reportedly reached large scale proportion by the 1700s and peaked in 1867 when more than 13,000 (62 liter) barrels of shark oil were exported. Greenland’s catches reached ~32,000 sharks per year in the 1910s. After WWII, a reinvigorated oil market gave new life to the Norwegian fishery, which peaked in 1948 at nearly 60,000 sharks, and then declined rapidly due to the rise of synthetic oil. Experts surmise that these fisheries took a significant toll on the population.

Greenland shark catches reported to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) since 1957 show a peak of ~200 t around 1960 declining to ~50t since the early 1980s. Germany reported the highest catches during much of the 1960s; Iceland has reported the most ever since.

In the 1970s, in response to complaints by fishermen about Greenland sharks eating their catch, the government of Norway hired a few vessels to cull the population.

In the mid 1980s, fishermen from Greenland were reportedly brought into Inuit communities in northeastern Canada to teach local hunters how to longline for Greenland halibut through holes in the ice. The frequently caught Greenland sharks became regarded as nuisances.

Exploitation today

Greenland sharks are still targeted by small scale fisheries in Greenland and Iceland, and taken incidentally in broader scale trawl, longline, gillnet, and trap fisheries targeting other species, particularly Greenland halibut. There are no estimates of discard mortality for Greenland sharks. Observers report some animals being released alive from commercial vessels; severing their tails to remove them from ice hole fishing lines is pretty much fatal.

While uses for Greenland sharks in Greenland are reportedly now limited to dog food, in Iceland, the species’ potentially toxic meat is fermented and dried to make the delicacy, Hákarl.

Icelandic vessels reportedly landed 60t of Greenland shark in 2014. Small-scale longline fisheries still target the species using longlines, but most landings are the result of incidental catch in net fisheries, according to Iceland statistics.

Greenland sharks are among the most commonly caught species taken incidentally in Canadian gillnet and trawl fisheries for Greenland halibut. The management plan for this fishery notes concern over this bycatch, but does not regulate it. A study of bycatch in Spanish fisheries targeting Greenland halibut just outside Canadian waters found Greenland sharks made up 8.7% of discarded biomass.

Scientists reported a marked increase in Greenland sharks (more than doubling to 500+ animals) caught in Canada’s Cumberland Sound after 2009 when longline fishing for Greenland halibut (conducted through the ice) expanded from winter into summer months. Hooked Greenland sharks tend to roll and become entangled in the fishing line, often resulting in damage to gear and/or the severing of the shark’s tail.

Greenland shark sport fishing operations, often promoting catch and release, have developed in Norway and Greenland.

A note about Greenland

As a largely self-governing part of Denmark, Greenland maintains some independent treaties and participates in relevant international agreements, while Denmark controls foreign affairs, including representation in international negotiations related to fishing. Denmark is an EU member; Greenland withdrew from the EU in 1985 over a fishing dispute, although partnership arrangements persist. As melting sea ice increases many countries’ interest in Arctic fisheries, Ministers from the Faroe Islands and Greenland have called for the right to act independently of Denmark with respect to fishing.

CONSERVATION POLICY OPTIONS

Finning bans

Bans on the wasteful practice of finning (slicing of a shark’s fins and discarding the body at sea) are the most common, basic safeguards for sharks. The adoption of finning bans by relevant Regional Fishery Management Organizations (RFMOs) obligates most fishing nations to follow suit. If Greenland sharks happened to be caught by US or EU vessels, their fins would need to remain attached through landing, while many other countries, including Canada, merely require that the weight of fins not exceed 5% of carcass weight. Canadian fishermen have been cited for cutting off the tails of Greenland sharks to remove them from fishing gear, which could be considered finning. It is essential to note, however, that — whereas essentially all shark fins have some value — there is no evidence that Greenland shark fins are worth enough to justify shipping costs, and Greenland sharks are almost certainly not caught for their fins (Clarke, 2016, pers. comm., August 15).

Species-specific protections

The EU is the only fishing entity relevant to Greenland shark that has prohibited (at least temporarily) their retention. Starting in 2012, the EU deepsea shark total allowable catch limit (TAC), which specifically covers Greenland sharks, has been set at zero. This measure applies through 2016; TACs for 2017 and 2018 will be set in late 2016.

The conservation status of the Greenland shark has not been assessed by Canada’s Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in terms of possible listing and protection under the Species At Risk Act (SARA). The species is considered a “mid-priority candidate” relative to this process.

Iceland and Norway prohibit the discarding of fish; all sharks caught must be landed and recorded. Banning retention would run counter to this approach, although these governments may consider means to minimize profit associated with species of concern.

Bycatch reduction

The relatively recent Canadian Policy for Managing Bycatch — which applies to commercial, recreational, and Aboriginal fisheries — aims to ensure sustainability, minimize irreversible harm to bycatch species, and account for all catch (whether retained or not). The policy is being implemented over time, according to national and regional priorities, and resource availability.

Suggested actions that could result from Greenland sharks being prioritized under this process include data and educational initiatives, limits on bycatch, spatial management, and gear modification. Similar outcomes could be presented as goals for other relevant countries and/or RFMOs.

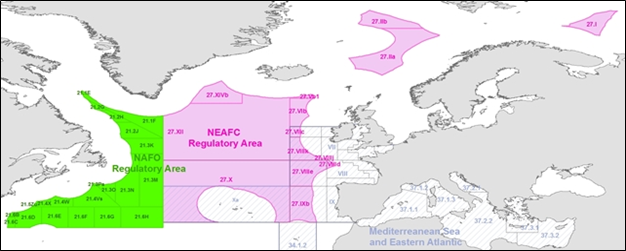

NAFO

Way back in 1949, during the development of the convention that would eventually underpin the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO), Denmark was reportedly instrumental in extending the Convention Area to include northwestern Greenland on the basis that species being fished in this region, particularly Greenland sharks, needed investigation and possibly protection. Today, NAFO Parties have yet to adopt any Greenland shark-specific safeguards. A 2005 binding NAFO measure does, however, ban shark finning, and obligate Parties to report shark catch data, ensure full utilization, encourage the release of live, unwanted sharks, and research, where possible, shark nursery areas and gear selectivity improvements.

NEAFC

The North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC) is the only international body to date that has taken policy action specific to Greenland sharks. In 2013, Parties — Iceland, Denmark (in respect of the Faroe Islands & Greenland), Norway, Russia and the European Union — adopted a binding measure to prohibit directed fishing for deepsea sharks, including Greenland sharks, in high seas areas under its jurisdiction, and encourage consistent action in national waters. The measure is set to expire in December 2016. A broader NEAFC measure on sharks adopted in 2015 obligates Parties to annually report shark catch data, require that all shark parts (except heads, guts and skins) are landed, prohibit at-sea removal of shark fins, encourage live release of unwanted sharks, and undertake (where possible) research into reducing shark bycatch and identifying key shark habitats.

New Arctic agreements

Melting sea ice is expected to create in the Arctic greater windows for fishing and a very different ecosystem. After years of talks, the five states that surround the central Arctic Ocean – Canada, Denmark (in respect of Greenland), Norway, Russia, and the US – signed in 2015 a voluntary declaration to prevent unregulated commercial fishing in high seas portion of this area, at least until stock assessments and management mechanisms are developed. They also plan a research program that takes into account Inuit knowledge to improve understanding of regional ecosystems. Iceland, China, Japan, South Korea, and the EU have since joined in negotiations. Further talks and a related scientific workshop are planned for the fall. Conservation NGOs are calling for a binding regional agreement, while urging more countries to follow the US in adopting precautionary fishing bans in national Arctic waters.

CITES

Concerns about international trade in deepsea shark liver oil and meat have been raised through the Animals Committee for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), but have been focused on gulper sharks of (Genus Centrophorus). Relatively little is known about the global market for shark products, with trade data on the relatively minor trade in shark liver oil and skin (compared to shark meat and fins) being extremely limited. As noted above, Greenland shark fins are not common in trade.

CMS

Greenland shark tagging projects are ongoing; recent results indicate that the species is sufficiently wide-ranging to qualify for listing under the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). However, Iceland and Canada (and several other potentially relevant countries) are not CMS Parties, and Denmark’s ratification of CMS does not extend to Greenland. Although CMS membership is not required for countries to participate in CMS conservation initiatives, this route seems rather indirect in terms of addressing Greenland shark conservation, at least for the moment.

So! What might be done to safeguard Greenland sharks?

Although there are many tools now available to help sharks, here are a few near-term policy actions that appear relatively feasible and relevant, given threats, previous commitments, and upcoming opportunities:

- At its annual meeting in November, NEAFC could renew its ban on targeted deepsea shark fishing, report on complementary national measures, and request further investigation by ICES of Greenland shark population status and risk;

- At its annual meeting in September, NAFO could establish a prohibition on fishing/targeting for Greenland sharks and/or all deepsea sharks, and request specific advice from the NAFO Scientific Council regarding status, needs, and means to reduce bycatch;

- Canada could prohibit landing and/or targeting of Greenland sharks (or all deepsea sharks) and work to minimize bycatch of this/these species in Canadian fisheries, as a matter of priority;

- The EU can extend its Greenland shark protection in late 2016 by setting 2017-2018 TACs for deepsea sharks at zero, and requesting specific scientific advice from ICES; and

- Arctic fishing countries could complete a binding agreement that prevents regional overexploitation and promotes a greater understanding of Arctic ecosystems.

I’m thrilled that this big, bad dogfish is getting so much love at this pivotal time! I hope the widespread, positive attention to remarkable new findings will spark not only further research into the biology of Greenland sharks, but also support for concrete actions to protect these exceptionally vulnerable animals from overfishing.

I love Greenland Sharks. The fact that people killed them for being a nuisance for fishermen sounds a lot like when the Canadian government used to kill Basking Sharks on purpose till 1970 for the same reason. It is sad that people kill things so freely without knowing hardly anything about them. Thank you for an interesting article!