Last week, a team of 10 Australian scientists announced that they had found the world’s first “shark hybrids”, offspring of individuals from two different shark species which had interbred. During a routine survey of Australian marine life, 57 sharks were found that physically resembled one species of shark, but had genetic markers inconsistent with that species. Subsequent genetic investigation revealed that these 57 animals were hybrids between common blacktip sharks (Carcharhinus limbatus) and Australian blacktip sharks (C. tilstoni).

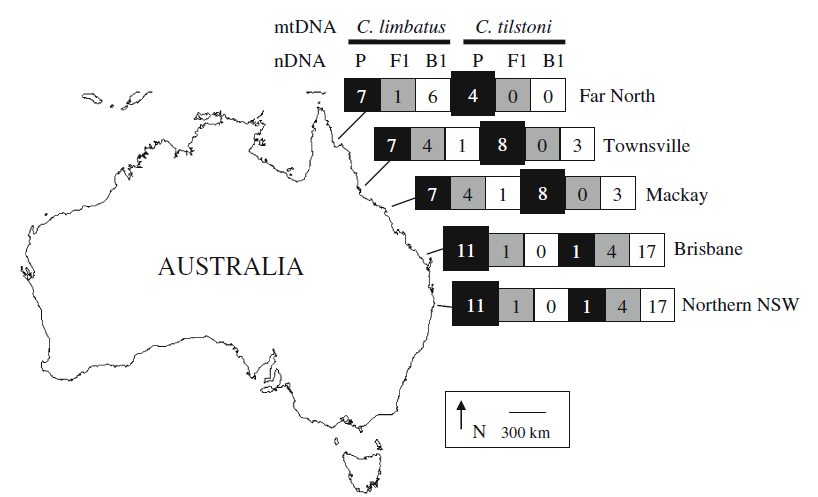

Some of these hybrids were “F1″, meaning that one parents was a common blacktip and one was an Australian blacktip. Others were “B+”(backcrossed), which means that one parent was a common blacktip/Australian blacktip hybrid, and the other was a “purebreed” of one of those two species. According to the study’s lead author, Dr. Jess Morgan of the University of Queensland, “our genetic marker tells us that these hybrids are ‘at least’ F1, and that these animals are reproductively viable and can produce an F2…the hybrids may be generations past F2 but the existing genetic markers can’t distinguish how many generations past the second cross have occurred.”

Genetic evidence and morphological characters have long supported the hypothesis that Australian and common blacktips are closely related, but distinct, species. They have detectable differences in their mitochondrial DNA, length at birth, length at reproductive maturity, and number of vertebrae. According Dr. Morgan, “The two blacktip species are very closely related (termed sister species) and this is probably why their hybridization has been successful. Over time the genes of species diverge away from each other due to random mutations.”

Common blacktips have a much wider distribution and are found worldwide, including throughout the more restricted range of the Australian blacktip. The area where the ranges of two species capable of interbreeding overlap is called a “hybrid zone”. Scientists expect to see more hybrid zones as climate change alters the ranges of numerous species.

Unlike most other species of fish, which reproduce by releasing eggs and sperm into the water column, sharks reproduce via copulation and internal fertilization. This means for each F1 hybrid, a male of one species physically mated with a female of the other. Different shark species often have varied mating behaviors, which was thought to make such hybridization extremely unlikely. Though hybrids have long been known in many other groups of organisms, this is the first time that hybrid sharks have ever been detected.

Additionally, both species are an important part of the Australian inshore shark fishery, and the discovery that they can hybridize has implications for the management of both species. Hybrids are often less reproductively fit, and if that is the case here, it means that both species may be less able to support a fishery than previously believed. However, Dr. Morgan says, “If the hybrids turn out to be fitter than their parent species then over time the two species will merge into one species, simplifying management.”

Finally, hybridizing with the more temperature-tolerant common blacktips has allowed for a range expansion beyond the tropical waters where Australian blacktips are commonly found:

This fascinating discovery has deservedly resulted in a great deal of media coverage. With many news stories involving sharks, climate change, or evolution, the mainstream media has a tendency misconstrue the science. This story involves all three of these issues, and the resulting news coverage hasn’t been entirely accurate. Presented below is a list of common inaccurate claims made by news reports about these hybrid sharks, and a summary of the relevant science.

Do other hybrid sharks exist?

The Huffington Post claims that these hybrid sharks are “unlike any other [shark] in existence”. While it’s true that none have ever been documented before, claiming that no other hybrid sharks exist is inaccurate because we simply don’t know. Just because something was only discovered recently doesn’t mean that it only came into existence recently, and just because we’ve never seen any others doesn’t mean that none are out there. This point was even raised in the press release associated with this discovery, which noted “other closely related shark and ray species around the world may be doing the same thing.” These animals are the first hybrid sharks to be detected by scientists, but are likely not the world’s only hybrid sharks.

“We suspect that there may be other hybrid elasmobranchs out there, and recommend that studies investigating sister-species with overlapping distributions consider including a nuclear DNA marker for species identification as well as using a mitochondrial DNA barcode (mitochondial DNA is maternally inherited and will miss hybrids),” Dr. Morgan said.

Is mating with a different species better than not mating at all?

The MSNBC article claims that this hybridization may be a reaction to overfishing, which has reduced the populations of both species. Basically, they are saying if an Australian blacktip shark has fewer other Australian blacktip sharks to mate with, it may be less resistant to mating with a common blacktip. In other words, “as fisheries are depleted, hybridization is a way to keep reproducing.”

While this is an interesting hypothesis, there is (so far) absolutely no evidence supporting it. Sharks have long generation times, so in order for backcrossed individuals (essentially grandchildren) to exist, the original hybridization detected in this study has to have been going on for at least several decades. That long ago, shark populations were much healthier than they are now.

Additionally, there is no evidence that individual sharks within a species struggle to find mates, even with today’s greatly reduced populations. Many species of sharks have mating aggregations, so even if populations were reduced, individuals could find each other. It is not known if either species of blacktip engages in this behavior.

The study’s authors did not mention this hypothesis in the paper itself, the press release, or any interviews that I can find. It seems to have originated in an interview with another shark scientist unrelated to this research project, and that scientist was merely proposing a possible explanation.

Dr. Colin Simpfendorfer, an expert on Australian shark fisheries and one of the study’s authors, said, “Both species of blacktips are target species in fisheries across northern Australia (including the area where hybrids were found). However, assessments suggest that they are relatively productive species and that populations are not at dangerously low levels. Unfortunately we know little about mating systems in these species (or most other sharks for that matter), including if they have specific mating areas, and if they do where they occur.”

Are blacktips planning ahead to protect themselves from climate change?

A common claim in news articles about this discovery was that the sharks were hybridizing to protect themselves from climate change. This was expressed most clearly in an AFP article (picked up by both Yahoo News and Discovery News), which stated ” the Australian black-tip could be adapting to ensure its survival as sea temperatures change because of global warming”. This claim displays an all-too-common lack of understanding of how evolution works.

While climate change can indeed negatively affect marine organisms like sharks, the logic behind this particular claim is a little hard to follow. It is unlikely (at best) that Australian blacktips would know that mating with common blacktips would result in offspring that could survive in more temperate waters. Additionally, evolution is not goal oriented. Females of many species look for a variety of traits before deciding which males to mate with (strength, fighting ability, size of antlers, etc.), but to my knowledge desired traits do not include a invisible ability to survive in colder water. Also, waters are getting warmer, so it is unclear why adapting to more temperate waters would be advantageous. Climate change is not specifically mentioned in the original article or in the press release, though both reference broader “environmental change”.

“We do not believe that climate change triggered the hybridization event,” said Dr. Morgan. “We do see that hybrid Australian blacktips have extended their range south into cooler waters suggesting that they may have a wider temperature tolerance than pure Australian blacktips. This increased temperature tolerance may make the hybrids better adapted to tolerate changes in water temperature in the future.”

Reader reactions

While the media coverage of these hybrid sharks has been occasionally inaccurate, reader comments left on the bottom of news articles are absolutely terrifying. CNN actually dedicated an entire blog post to their favorite reader comments from the original news story, and comments that didn’t make this list include rants against evolution, climate change, shark conservation, and science itself. Apparently, the scientists involved in this discovery hope to use it to simultaneously promote socialism and get incredibly rich while denying the Bible.

My favorite reaction to this discovery comes from conservative provocateur James Delingpole, who wrote a mocking post for the Telegraph’s blog entitled “Can climate change create deadly mutant sharks which kill us all?” It is often difficult to tell when Delingpole, the author of books such as “365 ways to drive a liberal crazy”, is being sarcastic or serious. However, it’s easy to tell (from this and many other posts) that he doesn’t understand science and is kind of a jerk.

Dr. Morgan has a message for these naysayers. “Please read our research article in Conservation Genetics before you attack the science. Not everything you read in the paper, see on the news or find on the internet is true,” she said. “I have enjoyed some of the rants, my current favourite is mutant sharks with lasers. ”

The bottom line

Kudos to this team of scientists for a fascinating discovery with important implications. I look forward to seeing follow-up studies determining if hybrids have different life histories, and how these life histories impact fisheries management. I also look forward to discoveries of many more hybrid sharks, which I expect will happen soon, and studies of how the presence of hybrids impacts forensic technology like DNA barcoding. However, these sharks are probably not the only hybrids in the world, they did not intentionally hybridize for the purpose of becoming more resilient against climate change, and they are not going to evolve frickin’ laser beams on their heads.

Allendorf, F., Leary, R., Spruell, P., & Wenburg, J. (2001). The problems with hybrids: setting conservation guidelines Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16 (11), 613-622 DOI: 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02290-X

Cheung, W., Lam, V., Sarmiento, J., Kearney, K., Watson, R., & Pauly, D. (2009). Projecting global marine biodiversity impacts under climate change scenarios Fish and Fisheries, 10 (3), 235-251 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2008.00315.x

Lavery, S. (1992). Electrophoretic analysis of Phylogenetic relationships among Australian Carcharhinid Sharks Marine and Freshwater Research, 43 (1) DOI: 10.1071/MF9920097

Morgan, J., Harry, A., Welch, D., Street, R., White, J., Geraghty, P., Macbeth, W., Tobin, A., Simpfendorfer, C., & Ovenden, J. (2011). Detection of interspecies hybridisation in Chondrichthyes: hybrids and hybrid offspring between Australian (Carcharhinus tilstoni) and common (C. limbatus) blacktip shark found in an Australian fishery Conservation Genetics DOI: 10.1007/s10592-011-0298-6

Pratt, Jr., H., & Carrier, J. (2001). A Review of Elasmobranch Reproductive Behavior with a Case Study on the Nurse Shark, Ginglymostoma Cirratum Environmental Biology of Fishes, 60 (1/3), 157-188 DOI: 10.1023/A:1007656126281

WONG, E., SHIVJI, M., & HANNER, R. (2009). Identifying sharks with DNA barcodes: assessing the utility of a nucleotide diagnostic approach Molecular Ecology Resources, 9, 243-256 DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02653.x

ok i am a 15 year old guy and i have a passion for sharks and honestly i understand mostly what this article says but can you plez explain how the ummmmm kind of how the genetics work? and could you plez tell me how i can get the word of that sharks need help or the ecosystem will crash and we are apart of that ecosystem so plez post more and e mail me if you have the time

Hi, Nick! I’m happy to explain anything you’d like in more detail, but could you please be more specific in your request?

For the first time I have learned that hybrid shark also exists.

ok well for one whats the F1 F2 mean ?

and i know this has nothing to do with this article but can i ask your opnion on the magalodon shark?

Fascinating write up, thanks for your thoughtful explanations and media critique. One question: you states “Hybrids are often less reproductively fit,” — but what about hybrid vigor? There are many examples of hybrids showing more adaptable traits than their parent species. In this very example, the hybidization has allowed for a range expansion.

Hybrids are not always less fit, but sometimes they are.

See “Muhlfeld CC, Kalinowski ST, McMahon TE, Taper ML, Painter S, Leary RF, Allendorf FW (2009) Hybridization rapidly reduces fitness of a native trout in the wild. Biol Lett 5:328–331”

Also, in this case a range expansion occurred, but with unknown effects on life history (age at reproductive maturity, number of offspring per litter, etc). Follow-up studies will answer those questions.

F1 is first generation (i.e. children), F2 is second generation (i.e. grandchildren) of original parents.

Great write up David, and good work keeping the media on task. I’m still not convinced that what’s reported are actual hybrids. Given the dataset they’ve used, I wouldn’t be able to rule out parapatric speciation and I’d be hesitant to base species ID on maternal markers, since mitochondrial introgression could be rampant in a secondary contact zone.

At minimum, I’d like to see more sequence- and frequency-based nuclear markers and an assessment of Isolation by Distance away from the contact zone. If IBD is very strong, it would be a good case for incipient speciation and not secondary contact.

I am pro-megaladon.

ok thank you i cant wait to read more

ok i have another question would this change their diet in any majour ways or aggression?

Check out the “Best of SFS” tab at the top of this page for a sampling of some of our favorite posts about many topics, including sharks.

Wonderful post WSM! I love the fact-checking spirit. Sadly, a lot of the media nonsense about climate change driving this possible hybridization was debunked by climate change skeptics eg WUWT while most of the science-o-sphere remained silent, until now!

Expect pushback from scientists that wrongly think the factual accuracy of the message doesn’t matter, eg, dopey scoldings like “don’t be such a scientist” via Gregor Hodgson on the coral-list here here: “For those scientists who continue to want to nitpick I strongly suggest that you read the excellent book by our colleague Randy Olson on why scientists are such poor communicators and how we can learn to do better.

http://www.dontbesuchascientist.com/

Note the title of the book isn’t Don’t Be A Scientist!

Thanks again David.

Thanks John!

If these are indeed separate breeding populations then some odor or visual cue involved in mate selection has allowed for the isolation despite C. tilstoni’s range being a subset of C. limbatus’s range. So if the hybrids are new- why now? If its not an alee effect- as Whysharksmatter posits- what changed? (My gut says if its not an alee effect then these hybrids are far more common than we thought and breeding occurring perhaps at the intersect of the two species size range.)

I have more knowledge about salmonids than sharks where the question of assortive mating would arise and why the larger common blacktop is mating with the smaller Australian blacktip. In salmonids we often see hybrids as an alee effect and I don’t think we can so readily assume that mate finding as a result of fishing pressure is not an issue as the above post assumes. Shark over harvest has been a problem for a lot longer than the recent increased publicity of finning.

And I think as has been posted we should not assume hybrid vigor as a given. In kokanee and sockeye crosses as an example we see a loss of vigor and we even call them the same specie.

I’m left with some questions as to how the U of Queensland press release was written http://www.uq.edu.au/news/index.html?article=24232:

A warning? A warning about what?

“Dr Jennifer Ovenden, an expert in genetics of fisheries species and a member of the scientific team said this was the first discovery of sharks hybridising and it flagged a warning that other closely related shark and ray species around the world may be doing the same thing.”

I’m not sure how they support this statement:

“Wild hybrids are usually hard to find, so detecting hybrids and their offspring is extraordinary,” Dr Ovenden said

The HRM-PCR assay method they used to identify the hybrids seems like it was developed within the last year or so.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03023.x/abstract

Whysharksmatter correctly points out we are looking at multigenerational hybrids. Its my understanding that C. tislstoni wasn’t accepted as a separate species until 1980. Given the fact that even the vertebrate count partially overlaps for these two species- I’m just not sure how they support the claim for these hybrids being extraordinary or recent. What seems to be recent is the assay and the sampling using the assay. In fact in one interview it was claimed that in some areas 20% of the population were comprised of hybrids. This would lead me to believe hybridization has been going on for quite some time and is not extraordinary. Unless someone shows me using the same type of assay work showing these hybrids are historically unique – I’ll remain skeptical. As I will about shark hybridization in general.

What range expansion? They have not shown that the hybrid has any better temperature tolerance than C. limbatus. Or for that matter C. tilstoni

“We do not believe that climate change triggered the hybridization event,” said Dr. Morgan. “We do see that hybrid Australian blacktips have extended their range south into cooler waters suggesting that they may have a wider temperature tolerance than pure Australian blacktips. This increased temperature tolerance may make the hybrids better adapted to tolerate changes in water temperature in the future.”

This paper in 2010 says C. tilstoni is not a tropical shark and extends over 1000km further south than was believed and well into temperate waters. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02770.x/abstract

I see nothing to show that C.limbatus and C tilstoni don’t completely overlap in their Australian range as there is evidence of the C. tilstoni as far south as Sydney. So I’m a little unsure how there has been any range expansion beyond what is found for either parent. Even if we limit C. tilstoni to tropical waters contrary to some recent work showing their range extending over a 1000km to the south and temperate waters– the hybrid would have no greater range than that of the common blacktop. So how does this quote by Dr. Overdon to Perh News make sense?

“Hybridization could enable the sharks to adapt to environmental change as the smaller Australian black tip currently favours tropical waters in the north while the larger common black tip is more abundant in sub-tropical and temperate waters along the south-eastern Australian coastline.”

Why do the scientists bring the issue of environmental change to the forefront when there seems to be no temperature gradient among the parent species and no extension of range for the hybrid? Or am I missing something?

Hi, Pat, and thanks for commenting! I was not an author on the paper and my background isn’t in genetics. I’ve also alerted the paper’s authors to your question, so hopefully they’ll answer your questions.

An interesting article. However is this really a hybridisation of two distinct species? Both sharks belong to the genus Carcharhinus, thus are closely related via a recent common ancestor. The two sharks therefore show vast genotypic, and (evidently enough from name alone), phenotypic similarities (both are still easily distinguishable as ‘black tips’, but are they clearly distinguishable from one another? I, for one, am uncertain). Both sharks live in similar habitats (although importantly separate ones normally (with the exception of the ‘hybrid zone’ where habitats overlap)). Given this, is the case not really that these sharks have begun to exhibit a founder effect from geographical isolation from one another, leading to gradual genetic drift so they show evidence for genetic variation beyond the average two members of the same species, but yet not enough of a difference to yet be two distinct species. What I am suggesting is that perhaps these two shark are still in the early days of divergent evolution to the extent that on rare occasions they are able to still currently interbreed – a ‘half way’ before the two have fully diverged into separate species. It is unlikely two distinct species would interbreed due to varying breeding habits and courtship behaviour. Moreover, it is important to know the fitness of the F1 generation as to whether they are sterile or not, as we often define a species as being able to produce viable (non-sterile) offspring. A thought provoking and interesting read!

Why Sharks Matter,

Thanks-I’ll be interested in hearing the response. I am always concerned about the potential for fishery management issues being taken hostage by the crisis of the day. Salmon restoration as an example has suffered terribly as the result of being more important as the poster animal for various environmental campaigns than as a restored fishery. (Admittedly my bias). Sharks unfortunately have much more to worry about currently than climate change -so am a little sensitive that resources might be diverted to this “popular” threat rather than increasing our much needed basic understanding of their biology, ecology and harvest pressures.

Good luck with your shark research and you might enjoy this fishery history written by one of the old guys:

http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/history/stories/fsh_sci_history1.html

WhySharksMatter,

Look at the map in your post and the distribution of the pure C. tilstoni– it looks like C. tilstoni is found across the entire study range– in fact peaking midrange along the coast rather than the more tropical northern waters. And seems to be a fairly small sample size to make any range expansion claims especially given the researchers do not show any site that has hybrids and no C. tilstoni.

Understandable concerns. For what it’s worth,know Dr. Simpfendorfer is an expert on all aspects of Australian shark fisheries and I can’t imagine him letting managers ignore important threats because of this.

Sure, animals move outside of normal ranges all the time (my lab tagged a Great Hammerhead that swam 1,000 miles north of their traditional range), but I think their point is that C.tilstoni is typically found in more tropical waters, and hybrids are found in higher concentration than C. tilstoni in coler waters.

“are they clearly distinguishable from one another”

They have different maximum sizes, different ages at reproductive maturity, and different numbers of vertebrae.

I’m a little surprised by the skepticism and “surprise” of some of the readers, particularly those who are biologists. But the discussion is fun…evolution is such a great topic. But these sorts of things happen all the time; populations diverge and speciate, or diverge and then subsequently converge again. Even recognized species can be stable while maintaining a hybrid zone where they overlap…there’s a good parrot example (also from Australia). These things keep life interesting…if you really want a lively debate we should talk about Hypoplectrus!

What a great topic! I’m a bit surprised by the skepticism and “surprise” by some of the readers, particularly those that are from trained biologists. These sorts of things happen all the time. Populations diverge and speciate, or they diverge only to subsequently re-converge and meld back into a single population. There also examples of recognized species maintaining hybrid zones where they overlap…sometimes the hybrid gets a species designation (there’s a good parrot example, also from Australia). That’s the nature of natural selection. If you really want a lively debate, we should talk about Hypoplectrus!

I remain unconvinced David

As you know, size really doesn’t matter – and when two sharks produce fertile hybrids and are identical to the point of having to cut them apart and use electrophoresis to tell them apart, I remain skeptical.

Occam whispers that they were not two valid species from the outset and that some taxonomist just wanted to immortalize a “national” endemic here – much like the recent spate of newly described “South Pacific” anemonefishes etc.

But the concept of species is of course the subject of innumerable debates, and my guru tells me that the best definition of a species is what a good systematist says it is, so who am I to raise any doubts!

“the best definition of a species is what a good systematist says it is”

Ha! Who’s your guru??!! Systematists argue over “species or not species” all the time. Thus the terms “lumpers and splitters.” There will always be examples of “diverged populations” in a state of flux…either moving towards speciation or away from it. Ultimately it is only the animals themselves that can decide whether not they are a species; that is why, for my dissertation, I heavily weighted my mate selection experiments when deciding what to do with the troublesome serranid genus Hypoplectrus. Now, 20 years later, the molecular crowd still have not been able to dispute the findings of a “bucket biologist.” Determining species from a gel can be pretty arbitrary…no offense…it is a powerful tool but field work is still important.

As for true systematists…I miss them…we are losing them each year and there are not many “new recruits.” I wish I had paid more attention in my own mentor’s class (C. Richard Robins)!

My argument of course would be that the animals themselves have decided that they are NOT a species! 🙂

This business seems to call into question exactly what we mean by ‘species’. Wikipedia is vague on the point.

It would hardly be news that Chinese people can interbreed with San Bushmen. Though they enjoy some morphological and genetic differences, and occupy different geographic and ecological niches, these facts hardly make them separate species.

I’d be interested to see an attempt to define ‘species’ with some explanation of how it applies in the case of these animals.

Awesome write up though I am still a bit on the fence. Either way it is great to see the issues in popular media addressed and informed discourse to boot 🙂

Great article David! You broke down every point so well and made it easy to understand that this was a great discovery and more research is needed to fully understand the implications of the hybridization of the two shark species.

“They have different maximum sizes, different ages at reproductive maturity, and different numbers of vertebrae.”

— So do many species along a large latitudinal gradient where temperature goes from tropical to temperate

[David Starr] Jordan’s Rule

Great points made by many. Speaking from a scientific perspective, I agree with Mike-we are always making discoveries and learning new things. I think it is important to realize that as our technologies advance, so can our understanding of the natural world. And while I am not a molecular expert, our capabilities with these tools are a constant evolution.

It’s easy to label new findings as the next big explanation for natural selection–but evolution is far more complex than we give it credit for. We should embrace these findings–they are another piece of the puzzle for a group of species that continues to fascinate and surprise us. And it is exciting as hell to be part of that!

Not sure there is generally much variation in vertebral count within a species regardless of latitudinal variation in range. Also these two species have different tooth counts which can vary some within a species.

I’ve really enjoyed watching the discussion here and think it’s a prime example of scientists interacting with the public on interesting topics. I see three main issues represented here being addressed to different degrees.

1. The novelty of the hybrids. I don’t spend a lot of time working with sharks, but apparently this is one of, if not the first, case of shark hybrids. That novelty certainly makes it newsworthy, but hybridization has been well documented in many marine systems, vertebrate and invertebrate, and the discovery of shark hybrids speaks more to sampling effort than to the uniqueness of this case.

2. Some people think about “species” on an ecological time scale as discrete units while others think of speciation on an evolutionary time scale, where “species” is more a category of convenience when describing a system, and the continuous process of speciation is what’s interesting. As an unapologeric member of the later camp, I’m less interested in whether x and y are distinct and more interested in the ecological processes that are driving the interactions between these two groups. Are they truly distinct, reciprocally monophyletic groups with secondary contact following complete differentiation or are they parapatric groups in the late stages of speciation that have reached, but not yet surpassed the threshhold of “species”. Both would be fascinating cases of evolution in action. That leads us to the third issue at hand:

3. The study does not adequately support the author’s conclusions. With apologies to the researchers, the design is tautological – species ID is determined by mitochondrial COI without addressing the potential for mitochondrial introgression (though the authors do acknowledge that in the discussion). The single microsatellite marker is insufficient to positively ID hybrids, though by using sequence polymorphisms, it is more accurate that a single size-based frequency marker. I’m not trying to be cynical, it’s a nice study and the authors are clear about the limitations. As the initial publication of a larger project, it provides a great intellectual framework for ongoing investigation, but it is certainly not the final word on blacktip hybrid zones.

The process of speciation runs along a continuum. Two populations become reproductively isolated from each other and over time DNA mutations accrue so that eventually the two populations become distinct species that are no longer reproductively compatible. The two blacktip species are on the edge of the population-species boundary. If the two species were freely and regularly hybridizing we would expect the mixed offspring to lose their species differences and take on intermediate characters. Over time this would merge the two species into one. This does not appear to be happening with the blacktips. Most of the animals caught are pure species suggesting that there may be a fitness cost to being a hybrid. We currently know nothing about hybrid fitness but would like to investigate this in the future.

We also know nothing about the timing of hybridization. The widespread discovery of hybrids suggests that the two species have been crossing for a long time, or at least hybridized a long time ago. However, the maintenance of pure species and, the absence of unique hybrid DNA, suggests a more recent time frame. We hope to answer this question by screening more nuclear DNA markers.

An important difference with this system compared to other fish hybrids is that the sharks have internal fertilization. Fish have external fertilization which limits mating preferences as eggs and sperm are released into the water column to mix. Mate choice provides an additional reproductive isolating mechanism for sharks.

The warning to researchers is to flag that mitochondrial DNA barcoding, the classic genetic method for identifying species, fails to detect hybrids. This is because mitochondrial DNA is only inherited from the mother. If the species under investigation are closely related, with overlapping distributions, then scientists should consider including a nuclear DNA marker in their species identification toolkit. We had been genotyping the mitochondrial DNA of the sharks in our study for 2 years before we discovered the DNA:morphology mismatch. Without the mismatch we would never have known the hybrids were there.

Thanks to everyone out there for your interest in this research. It is great to have so much support and encouragement.

Jess Morgan