Cultural Heritage is a bit of a tough concept when working in areas beyond national jurisdiction. By definition, the places being considered for deep-sea mining by the International Seabed Authority exist at least 200 nautical miles from land and human habitation. Even most submerged archeological sites lie on continental shelves within nations’ exclusive economic zones. But humans have been explorers and voyagers since the very beginning, and places of significant cultural value do exist in the deep ocean. Some of those sites are the very ore deposits that the ISA seeks to exploit.

Deep-sea hydrothermal vents were first discovered in 1977 and have significant cultural and scientific value as sites of dramatic biological novelty. Hydrothermal vents have inspired generations of researchers, explorers, and filmmakers. The first deep-sea marine protected areas were established around historically important hydrothermal vent fields. The ISA recognizes within the draft regional environmental management plan for the Mid-Atlantic Ridge that there are sites in need of precaution which includes active hydrothermal vents that have been studied for decades. Several hydrothermal vent fields on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge fall within high seas marine protected areas through the OSPAR Convention.

Hydrothermal vents are the “easy” case for cultural heritage. They’re spatially discrete sites that have been extensively studied and have contributed materially and tangibly to expanding our scientific knowledge. And they’re stunning. Exploring a vibrant vent system is the closest any of us will come to exploring an alien world. They inspire scientists, but also artists, filmmakers, storytellers, and poets.

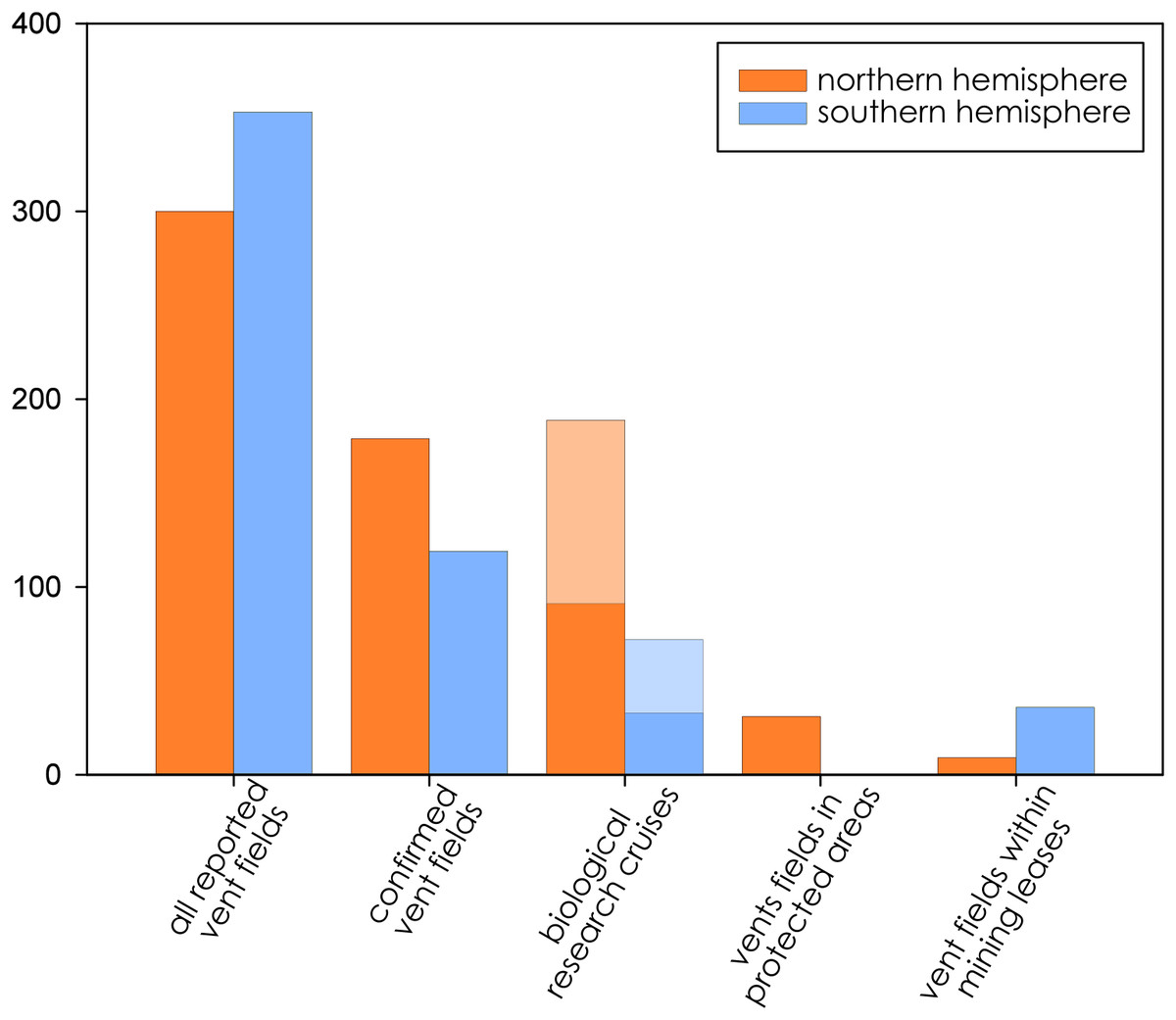

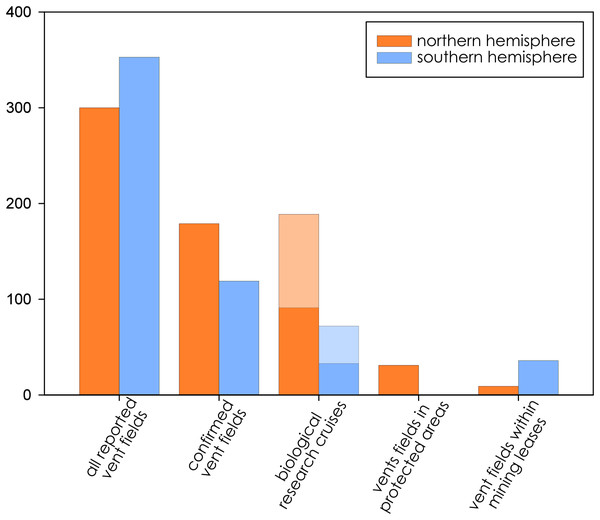

Beyond that, advocates for vent protection come from wealthy nations that have significant investments in deep-sea research capacity. In a study I conducted with Dr. Diva Amon back in 2019, we determined that the majority vents targeted for extraction (not just those within ISA lease blocks, but also those that fall those within national waters) were located in the global south, while all vents that fell within some form of protected area were located in the north. Part of that is down to the vagaries of exploration, but part of that is tied to who has the resources and influence to establish protected areas over potentially valuable mineral resources.

Voyagers have crossed the Pacific for thousands of years. ISA issued lease blocks in the northwest Pacific, particularly those in close proximity to the Mariana arc, are located in the path of traditional Micronesian voyaging routes. Deep-sea mining leases occur within Micronesian and Polynesian voyaging regions, areas where traditional navigators established and maintained millennium-spanning connections between remote islands.

Not all cultural heritage sites are places of excitement and discovery. The Middle Passage, a region of the Mid-Atlantic that reaches from West Africa to the Caribbean, encompasses the historic route through which millions of enslaved people were transported to the new world. Not everyone survived that journey. The Middle Passage is a vast maritime graveyard for up to 2 million enslaved men, women, and children. “The remains of the slave trade are tangible and intangible heritage that should be memorialized as the final resting place of the victims of the slave trade” said Ole Varmer, one of the co-authors on a paper advocating that the ISA recognize the tragic history of the region.

The Pacific is its own kind of maritime graveyard, with ships and planes from the Second World War scattered across the seafloor. Shipwrecks present a unique case, as they are both tangible cultural heritage and in some cases, are, themselves, strategic resources. Low-background steel is steel from vessels that sunk before the Trinity Test on July 16, 1945. All steel produced after the dawn of the atomic age contains trace radionucleotides which interfere with extremely sensitive scientific equipment, including neutrino and gamma-ray detectors, Geiger counters, as well as radiation detectors on spacecraft. Steel made before the first atomic bomb is essential for this equipment, and much of that surviving steel is found on wrecked ships from the world wars. Low background lead, like that found in the ballasts of even more ancient shipwrecks, has similar properties.

The deep ocean also represents an archive of the past. Because of the way that nodules and crusts form, polymetallic nodules may contain several million-year-old fossils, particularly shark teeth and crusts have been found with fossil embedded within them. One was just recently found during an EV Nautilus expedition.

All of which is to say that there are a many scenarios in which a deep-sea mining contractor’s claims may intersect with cultural heritage sites, both tangible and intangible. How that heritage is recognized and defined in areas beyond national jurisdiction where resource extraction is occurring presents a challenge that is unique to the work of the International Seabed Authority. The ISA Council will be discussing how we define intangible cultural heritage next Wednesday.

Southern Fried Science is free and ad-free. Southern Fried Science and the OpenCTD project are supported by funding from our Patreon Subscribers. If you value these resources, please consider contributing a few dollars to help keep the servers running and the coffee flowing. We have stickers.