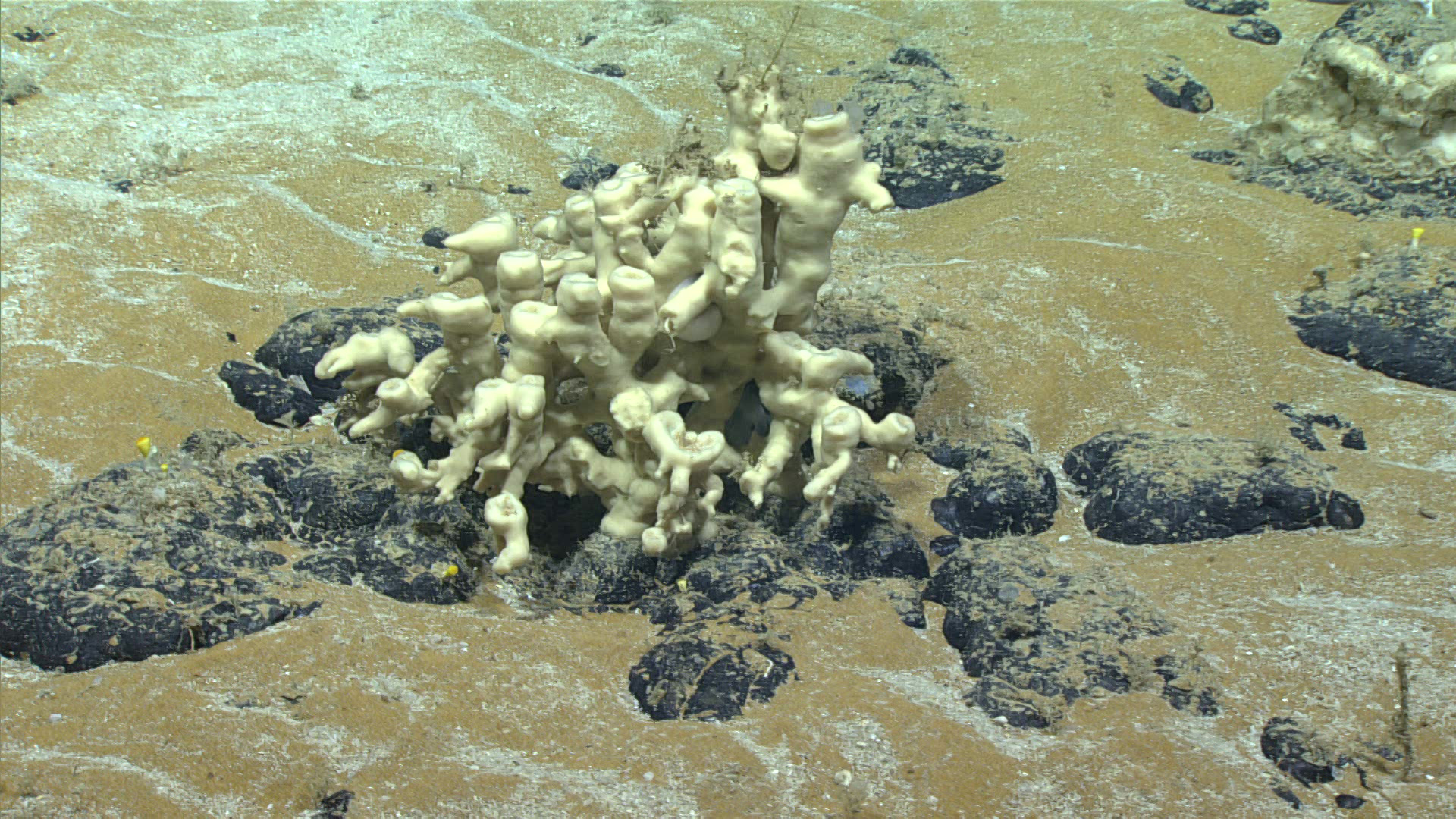

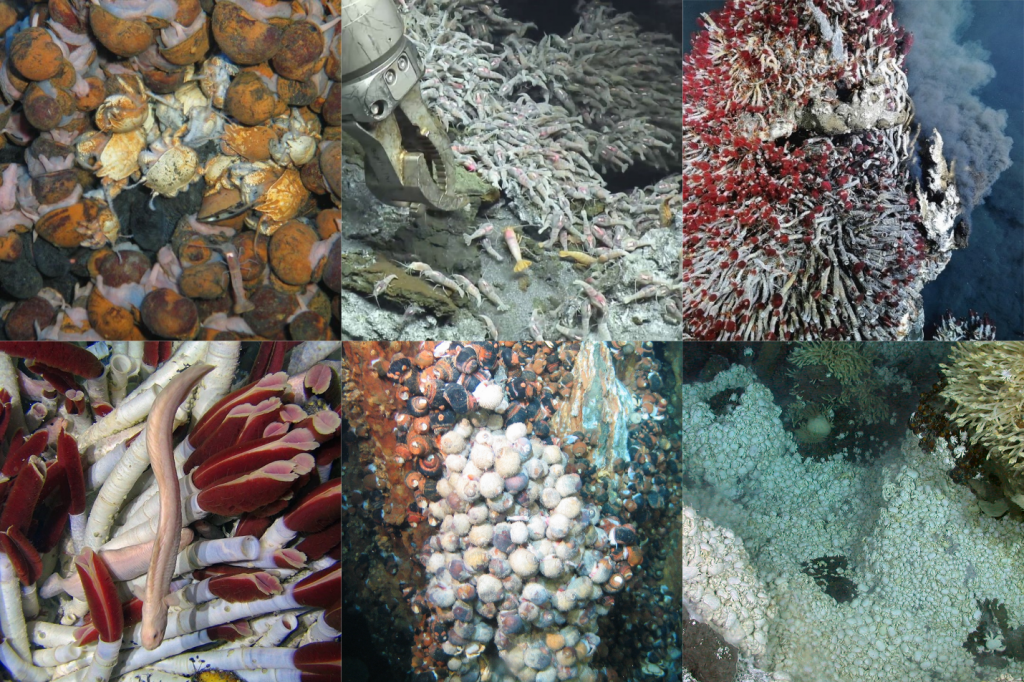

“When the RV Knorr set sail for the Galapagos Rift in 1977, the geologists aboard eagerly anticipated observing a deep-sea hydrothermal vent field for the first time. What they did not expect to find was life—abundant and unlike anything ever seen before. A series of dives aboard the HOV Alvin during that expedition revealed not only deep-sea hydrothermal vents but fields of clams and the towering, bright red tubeworms that would become icons of the deep sea. So unexpected was the discovery of these vibrant ecosystems that the ship carried no biological preservatives. The first specimens from the vent field that would soon be named “Garden of Eden” were fixed in vodka from the scientists’ private reserves.”

Thaler and Amon 2019

In the forty years since that first discovery, hundreds of research expedition ventured into the deep oceans to study and understand the ecology of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. In doing so, they discovered thousands of new species, unraveled the secrets of chemosynthesis, and fundamentally altered our understanding of what it means to be alive on this planet. Now, as deep-sea mining crawls slowly towards production, we must transform those discoveries into conservation and management principles to safeguard the diversity and resilience of life in the deep sea.

Though research at hydrothermal vents looms large in the disciplines of deep-sea science, relative to almost any terrestrial system, they are practically unexplored. Over the last 2 years, Drs. Andrew Thaler and Diva Amon have poured through every available cruise report that made a biological observation at the deep-sea hydrothermal vent to assess how disproportionate research effort shapes or perception of hydrothermal vent ecosystems and impacts how we make management decisions in the wake of a new form of anthropogenic disturbance.

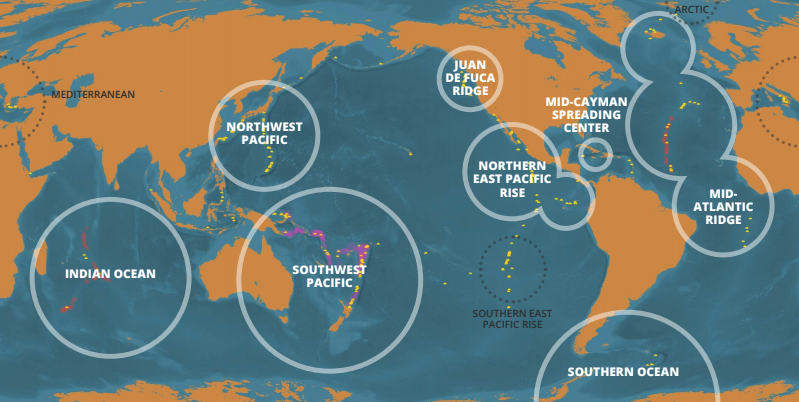

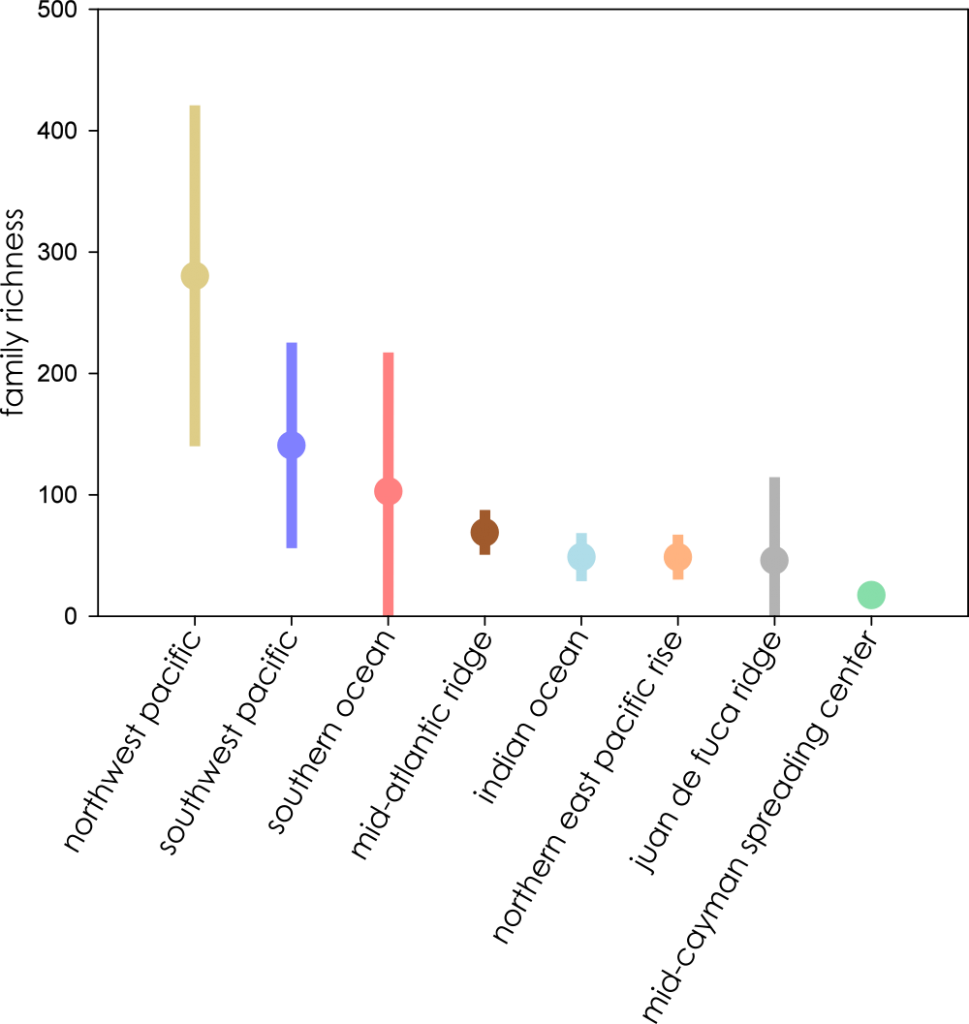

In a paper published today, they report on the results of this multi-year endeavor examining the history of deep-ocean exploration from the primary documents produced from each voyage. “A few major regions are disproportionately represented in the expedition data,” says Dr. Thaler, “Places like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and East Pacific Rise have received the sea lion’s share of research effort, which places like the Southern and Indian Oceans are practically unexplored. When we go to make environmental assessments of the impact of mining on hydrothermal vents, we’re drawing on data from very different ecosystems. It’s like trying to understand the impacts of logging in a tropical rainforest, but only using forestry data from the Pacific Northwest.”

They examined 262 cruise reports covering the global extent of hydrothermal vent ecosystems and compiled the first global assessment of vent biodiversity normalized against research effort. In doing so, they revealed critical exploration priorities, particularly the Indian Ocean, which is both relatively unexplored and currently threatened by deep-sea mining (recently, the scaly-foot snail received an IUCN Red Listing for potential threats posed by deep-sea mining of hydrothermal vents).

In reviewing these cruise reports, Thaler and Amon also made some interesting observations about the history of deep-sea exploration. On two separate occasions, researchers almost discovered hydrothermal vent a decade earlier than the 1977 Knorr cruise. In one case, an expedition to the Indian Ocean Triple Junction was taking chemical measurements almost directly on top of a known vent field, but they had to abort operations and return to port when a crewmember became ill. On another expedition, the RV Eltanin photographed the periphery of a hydrothermal vent community in the Southern Ocean, but they failed to capture the plume, and since they didn’t know what they were looking at, they simply noted the increased biomass and moved on.

“It’s fascinating to think what the history of deep-sea vent exploration would look like if the first discoveries occurred in the Indian and Southern Oceans, rather than the East Pacific Rise and Mid-Atlantic Ridge,” says Thaler.

The most dramatic result was the observation of a stark North/South divide among research effort and mining priorities. The Northern Hemisphere was disproportionately represented among the research data, and all current marine protected areas that contain hydrothermal vents are found in the North. However, though a few mining exploration leases have been issued for the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the overwhelming majority of vents threatened by deep-sea mining are in the Southern Hemisphere.

Says Thaler, “We study the North. We protect the North. But, overwhelmingly, we’re planning to mine the South.”

Read the full, open access paper “262 Voyages Beneath the Sea: A global assessment of macro- and megafaunal biodiversity and research effort at deep-sea hydrothermal vents” at PeerJ!